In Blood and Faith: The Purging of Muslim Spain, 1492-1614, Matthew Carr explores how, following the 1492 conquest of Granada, the sixteenth-century Spanish monarchy conducted peninsula-wide expulsions and conversions of Muslims as well as Jews. Ed Jones finds in the book’s historical analysis a valuable cautionary tale for contemporary public conversations surrounding immigration and integration regarding the consequences of legitimating fear and violence.

Blood and Faith: The Purging of Muslim Spain, 1492-1614. Matthew Carr. Hurst. 2017 (PB edition).

Four hundred years later, the destruction of the Moriscos is an example of what can happen when a society succumbs to its worst instincts and its worst fears in an attempt to cast out its imaginary devils.

The closing lines of Matthew Carr’s Blood and Faith: The Purging of Muslim Spain, 1492-1614 are a lucid illustration of the salience of his book in today’s world. Carr gracefully explores the way fifteenth-century Muslims, Jews and Christians who inhabited the Iberian Peninsula understood one another, before plunging into a story of conquests, crusades, assimilation and the expulsion of Jews and Muslims.

In Carr’s telling, following the 1492 conquest of Granada, the sixteenth-century Spanish monarchy gave in to fanatical Christian tendencies and conducted peninsula-wide conversions and expulsions of both Jews and Muslims. Those Muslims who converted to Christianity were allowed to remain in the peninsula and became known as ‘Moriscos’. However, a culture of fear and zealotry gained strength and culminated in the 1609 edict accusing the Moriscos of heresy, which led to the expulsion of tens of thousands. Seventeenth-century political economists bemoaned the damage this population loss inflicted on Spanish agriculture, and would blame Spain’s subsequent economic decline on the effects of this religious zealotry.

Carr’s work belongs to the historiography on Great Powers: one that seeks to explain the rise and fall of empires and states. In this regard, the work explores how Spain’s self-perceived need to remain at the helm of Catholic Europe pitted it against Protestant and Muslim nations alike. Stoking the fear of invasion, domination and encirclement of the peninsula only encouraged short-sighted and tyrannical grand gestures against the Muslim population, and ultimately hindered Spain’s peninsular economy.

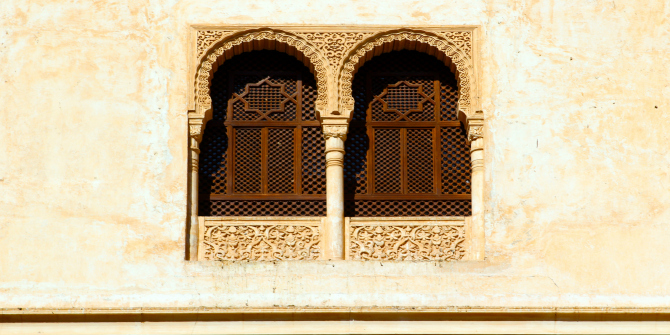

Image Credit: Alhambra, Granada (Barbara Eckstein CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: Alhambra, Granada (Barbara Eckstein CC BY 2.0)

It is nonetheless rather regrettable that Carr does not frame his study within a broader historical context that could include the focal relationship between the dynamics of the conquest of Granada and that of America – for this, one may read John Elliott’s body of work, particularly his seminal book Imperial Spain: 1469-1716, to learn how the narrative and practices of the former served as a blueprint for the conquistadors of the New World. Carr’s account also turns on a number of tropes that have long been discredited by the historiography surrounding Spain’s medieval fanaticism. The failure to acknowledge how Spain’s treatment of Muslims contributed to the ‘Black Legend’ – a narrative that saw Spain’s backwardness as the result of the protracted effects of institutions such as the Inquisition – undermines some of the analysis.

Carr’s work is best understood as an allegory to illuminate present dilemmas about migration and integration. In that sense, Carr navigates issues of assimilation and integration rather elegantly, and arrives at carefully considered conclusions with his deft analysis of the events that led to the expulsion and its aftermath. Indeed, Carr has written a valuable cautionary tale for the public on the pathways that crystallise imaginary evils. And it is only in the book’s epilogue that the echoes between past and present can truly be heard, and where Carr carves out the most alarming connections between the seemingly distant practices of late-medieval Spain and today’s world.

Carr shows that the spread of secularism in the twentieth century failed to act as a barrier to ethnic cleansing. Instead, bigotry and hatred have found new forms of legitimation and new outlets for their discourse. Technological changes have equally failed to act as a bulwark. Rather, in many ways, they have amplified these voices. For all of modernity’s progress, the construction of the other appears to be made from the same substance. As Carr suggests, today’s notion of Muslims as the ‘enemy from within’ echoes past formulations of the Morisco as a ‘domestic enemy’.

This febrile antagonism both resembles and encourages a narrative of fear, aided by metaphors of contagion and metastasis that serve primarily to dehumanise migrants. As Carr shows, these narratives would also be applied to Jews of nineteenth-century and early-twentieth-century Europe. Too often this logic has directly informed contemporary policies of assimilation which impose a model of social integration onto an imagined community, rather than negotiating cultural and social differences between host and guest cultures. Carr’s hope is that the book will convey the flawed logic of forced assimilation, a government approach that only spurs distrust and antipathy.

At the time of first writing this review, a van had just ploughed through the busiest pedestrian street in Barcelona, Spain’s second largest city. The incident took place on the same day that the frontier between Ceuta and Morocco was reopened, after it was shut for ten days due to several attempts to jump across the frontier. A few hours earlier, the Spanish spokeswoman for the UN’s refugee commission stated Spain lacked ‘the resources and capacity to protect the rising number of refugees and migrants reaching it by sea’. The statement was delivered in response to events earlier in the week, when the Spanish coastguard reported 600 migrants had been rescued from drowning, including a baby.

Making sense of these events and formulating policies to respond to the core problems that perpetuate them is no easy challenge. Blood and Faith makes clear that bigoted, short-sighted, self-seeking grandiose gestures are not the solution. Just a few weeks after the Barcelona attack, Donald Trump announced the end of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which protected close to 800,000 undocumented immigrants, once brought to the US as children, from deportation. The narrative surrounding the decision relied on the dehumanisation of Mexican immigrants, illegal or otherwise, a narrative that may have been familiar to a seventeenth-century Spaniard.

Can books like Carr’s spur the public conversation into a historically-minded approach to the future? It was the Spanish-born philosopher Jorge Santayana who stated the famous dictum about the perils of repeating history, and in doing so, displayed some of the prejudices that still haunt political discourse in our times: ‘progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness […] and when experience is not retained, as among savages, infancy is perpetual. Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.’ We must remember to face our devils, imaginary or otherwise, through the better angels in our nature.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article is provided by our sister site, LSE Review of Books. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Ed Jones – University of Cambridge

Ed Jones is a graduate of the LSE and a PhD Candidate in History at the University of Cambridge, with a focus on early modern Spain.

Find this book:

Find this book: