Opinion polls suggest six parties will enter the Bundestag in Germany’s election on Sunday, two more than crossed the electoral threshold in the last elections in 2013. But what does this apparent fragmentation of the German party system mean for the diversity of candidates, particularly in terms of the fair representation of women and minority groups? Paul C. Bauer and Julia Schulte-Cloos present a detailed analysis of the numbers of women and foreign-born candidates on each party’s candidate list. They find that parties on the left/libertarian end of the scale are more inclusive of women, but that the left-wing Die Linke and right-wing AfD have the highest percentage of foreign-born candidates.

Opinion polls suggest six parties will enter the Bundestag in Germany’s election on Sunday, two more than crossed the electoral threshold in the last elections in 2013. But what does this apparent fragmentation of the German party system mean for the diversity of candidates, particularly in terms of the fair representation of women and minority groups? Paul C. Bauer and Julia Schulte-Cloos present a detailed analysis of the numbers of women and foreign-born candidates on each party’s candidate list. They find that parties on the left/libertarian end of the scale are more inclusive of women, but that the left-wing Die Linke and right-wing AfD have the highest percentage of foreign-born candidates.

Ahead of Germany’s federal election on Sunday, opinion polls indicate that the next parliament will be composed of six parties. In addition to the Liberals (FDP), who surprisingly failed to surpass the five percent threshold four years ago, the future parliament is likely to feature a populist radical right party, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), which is unprecedented in Germany’s post-war history.

As chances are that six parties will move into parliament, the pool of party lists and candidates has substantially grown compared to the last election. The total number of candidates has grown by 8.5 percent as compared to the 2013 election. This poses the question whether the growth in numbers is accompanied by an increase in diversity. Research shows that the diversity of candidates is important in 1) encouraging political participation and 2) the future political activism of minorities, a finding which is equally valid for female candidates as well as candidates from ethnic minorities.

We analyse the German candidates for the upcoming election by considering the distribution of women and candidates not born in Germany across parties and regions. We rely on a list of 4,828 candidates provided by the federal returning officer of Germany. Our primary focus is on parties that have a high probability of getting into the Bundestag as predicted by zweitstimme.org.

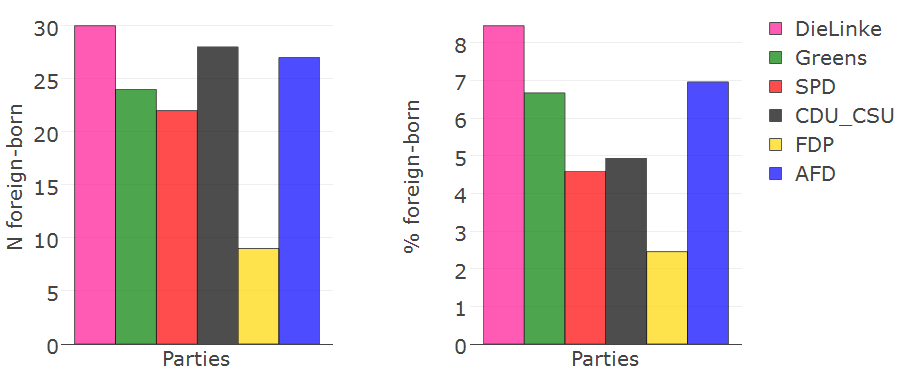

While our findings confirm expectations regarding the gender balance across parties, namely that it is highest among left-libertarian parties, the distribution of foreign-born candidates does not follow this pattern. Instead, the anti-immigration party AfD has the second highest share of candidates born in a foreign country, after Die Linke.

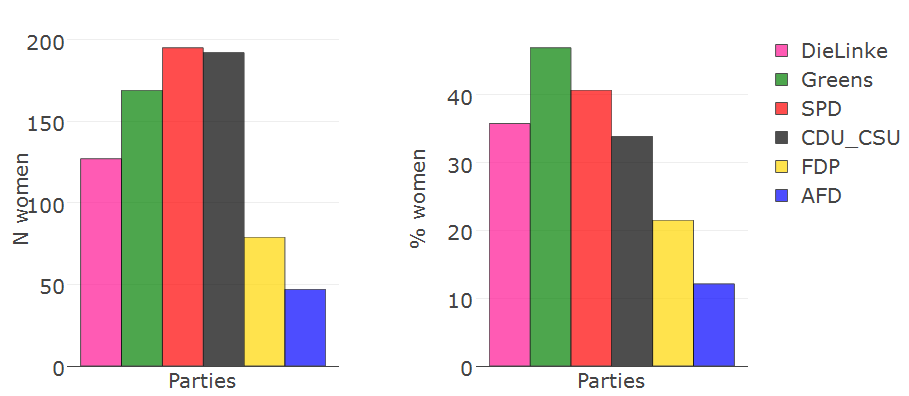

Figure 1: Women across parties

Note: Compiled by the authors.

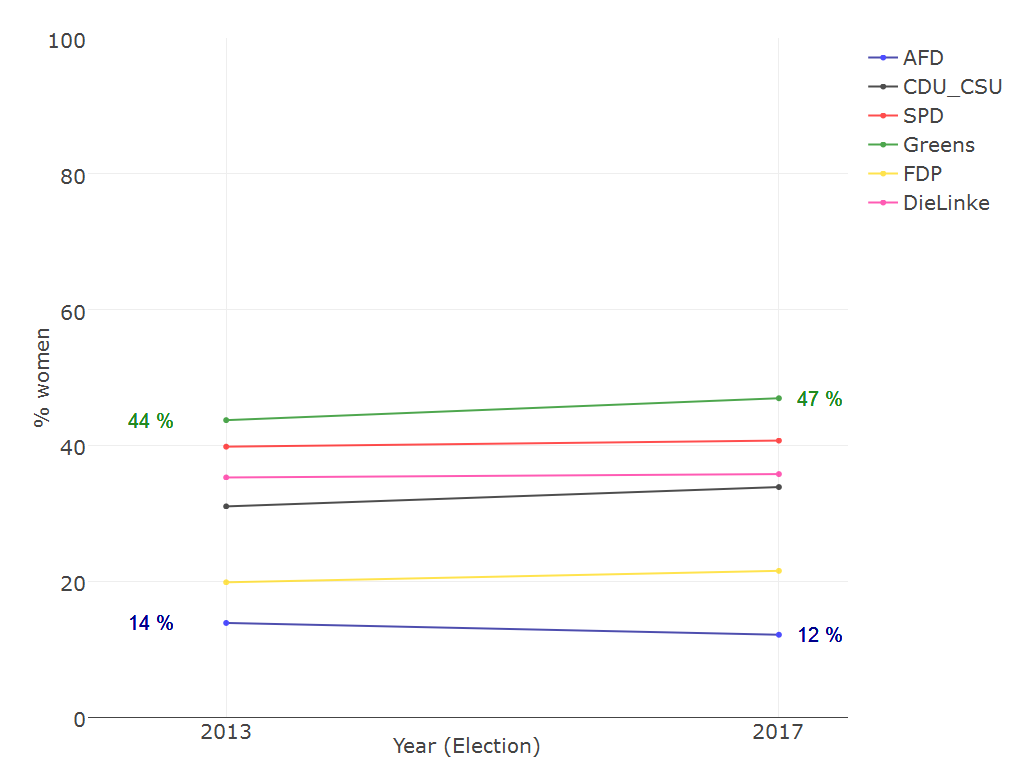

Among all candidates running in the federal election, only every third candidate is a woman (29%). The party with the lowest share of female candidates is the AfD with around 12% (see Figure 1). The AfD is also the only party whose share of female candidates has decreased compared to 2013 (see Figure 2). In stark contrast, almost every second Green candidate is female (ca. 47%).

Figure 2: Women across parties, across time

Note: Compiled by the authors.

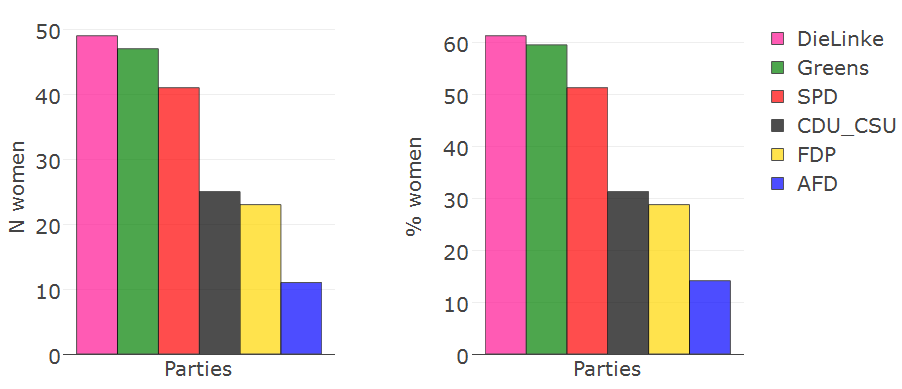

In the German mixed electoral system, voters have two votes: the first to choose among direct candidates from their electoral district, the second to choose among party lists, both of which are listed on the state-specific ballot. The party lists mention the top five list candidates. As most voters do not have information on the share of female candidates among parties, the first five candidates on party lists may present a relevant cue. As shown in Figure 3, among the top five positions across the party lists of the six biggest parties across all states (N = 477), the share of women decreases when moving from left to right along the political left-right spectrum.

Figure 3: Women among top five party state-list positions

Note: Compiled by the authors.

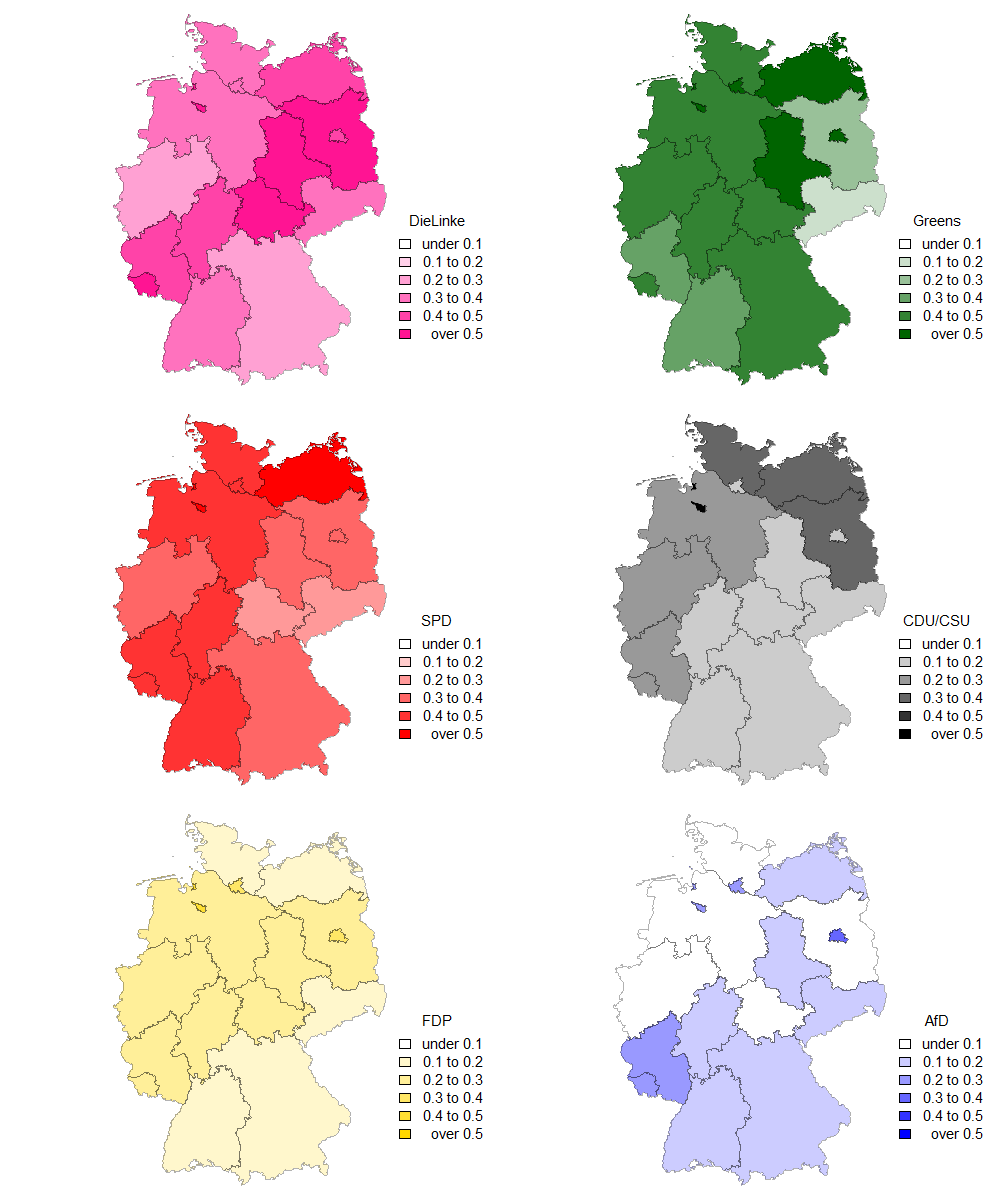

Rather than just focusing on the top five positions on party lists, Figure 4 visualises the average share of women among all top five party list candidates and all direct candidates (N = 1,851) per party per state. In other words, we measure the share of female candidates mentioned on ballots per state per party. These are all candidates who either directly run for office in one of the 299 German electoral districts and/or run among the top five on the party lists within the states.

Interestingly, in addition to the strong variation across parties, we also find strong regional variation within parties. The share of women among candidates on voting ballots of the Green party ranges from below 20% to more than 50%. The CDU/CSU, another party with strong regional variation, has a high share of female candidates in the former GDR states – this share includes the candidacy of current chancellor Angela Merkel. In Southern Germany, in contrast, the share drops below 20%.

Figure 4: Women across parties, across states (proportion, click to enlarge)

Note: Compiled by the authors.

The candidacies of ethnic minorities may encourage other minority members to cast a vote on Election Day or engage in politics as well. While it is challenging to collect data on the migrant background of candidates whose parents or grandparents have migrated to Germany, the official data of the Federal Election Commissioner include candidates’ places of birth.

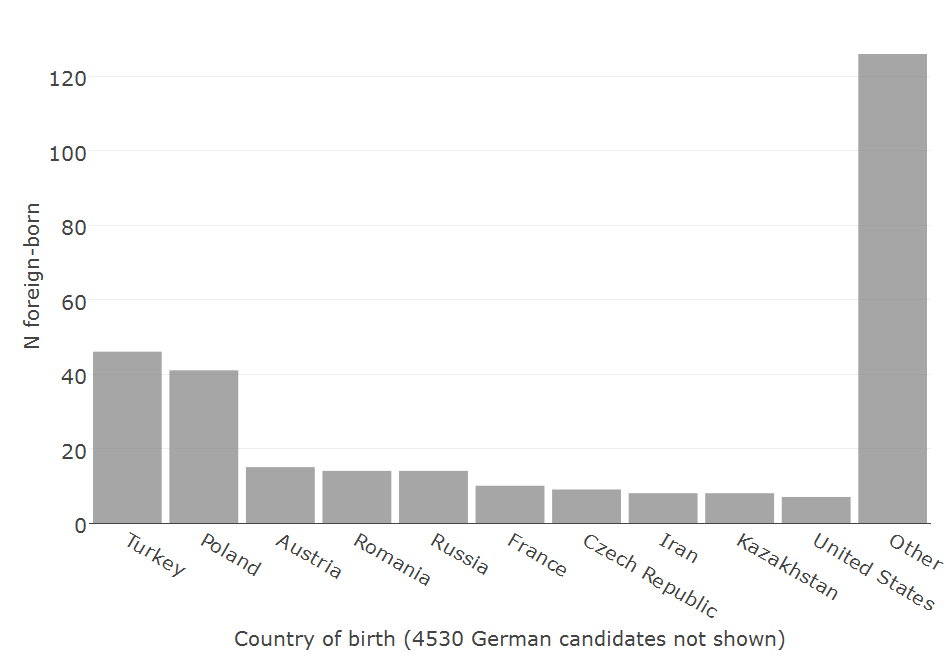

In other words, as a rough approximation of migration background we consider whether candidates were born in a foreign country and migrated to Germany. By automatically geocoding the place of birth of all 4,828 candidates, we obtain a variable indicating the country of origin. The overwhelming majority of candidates running for office in the 2017 federal election were born in Germany, 4,530 out of 4,828 candidates. As shown in Figure 5, the largest groups of foreign-born candidates are from Turkey, Poland, Austria, Romania, Russia, France, and a few other countries.

Figure 5: Countries of origin across all foreign-born candidates

Note: Compiled by the authors, total N = 298.

Figure 6 illustrates that the highest share of candidates born in a foreign country can be found among candidates of Die Linke. Surprisingly, the anti-immigration party AfD features the second greatest share of candidates not born in Germany.

Figure 6: Foreign-born candidates by party

Note: Compiled by the authors.

Figure 7 provides a more refined view and illustrates that in contrast to Die Linke, which features mostly candidates from Turkey, candidates in the AfD instead originate from Central and Eastern European countries. The AfD’s foreign-born candidates stem from countries like Poland, Romania and the Czech Republic. Generally, however, the share of candidates not born in Germany is low across all parties.

Figure 7: Countries of origin across parties

Note: Compiled by the authors.

Commentators expect a fragmentation of the political parties represented in the 19th German Bundestag. The number of candidates and party lists running on Sunday has grown. Focusing on two key aspects of representation, namely gender and migration background, this blog post highlights the variation across and within parties.

Our findings confirm expectations of a greater gender balance among left-libertarian parties, which may stem from the fact that they embrace gender-equal politics. We assume that this gender-balance is sustained by a self-reinforcing “role-model effect” that mobilises future political activists. In terms of country of origin, the pattern is less systematic across parties. While our analyses do confirm an intuition of greater diversity of candidates among Die Linke and the Greens, the anti-immigration party AfD features the second greatest share of candidates that were not born in Germany.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Paul C. Bauer – Mannheim Centre for European Social Research

Paul C. Bauer – Mannheim Centre for European Social Research

Paul C. Bauer is a research fellow at the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research (MZES). His areas of research include political sociology and research methods. He tweets @p_c_bauer

Julia Schulte-Cloos – European University Institute

Julia Schulte-Cloos – European University Institute

Julia Schulte-Cloos is a PhD candidate with a specialisation in comparative politics at the European University Institute (EUI), Florence. Her research interests include electoral behaviour, party politics, and quantitative research designs.

Congrats for the article, a very interesting read. In terms of minorities feeling represented, ethnicity/country of birth of parents would be perhaps more important than country of birth. Are those data available?

Thank you Michele. Unfortunately, no such data is available. Any analysis with a good measure of migration background would be extremely insightful.

The numbers of women candidates are not bad by comparison with some other countries, but we can still do more here. There is a question of what Merkel does for equality. She might serve as an example to other women (the “role model” effect that is mentioned here). But maybe there is also inertia here. There is a feeling we have a female leader, we don’t need to do anything more. The changes from 2013 to 2017 in the chart here show not much progress.

Nice article, thank you both! Correct me if i am wrong but one explanation for the paradoxicle finding of high shares of foreign born in the Afd might be that they are Spätaussiedler and the like. Post-1991 immigrants who entered Germany and were privileged over other immigrants because of their “possible” German ancestry. Members of this group are politically often conservative and populate the “association of displaced persons” – a ultra nationalist right wing organization that lobbies for the right of post-WW II displaced Germans and their ancestors.

With that in mind, foreign-born in the right-wing AfD and the left-wing Die Linke are very different populations with very different political stances and very different in terms of their position towards diversity.

@Michele Thank you. Unfortunately no such data is available. I agree, an analysis with a good measure of migration background would be extremely insightful.

@Markus You are raising some interesting points. In principle such a “Merkel = role model” effect may be testable in experiments.

@Florian Thank you. Yes, we had a similar intuition but refrained from stating any such conclusions.

hi there, thanks for your article and the work. I am particularly interested in the “ethnic” composition of foreign candidates across the political spectrum. Two questions: I was wondering if, given that “other” nationalities is the largest category, there is any way to categorize them (as to continents, regions, majority religion, race, etc.?) Do you provide your dataset to public use? And second question: What about socalled migration background candidates, i.e. individuals born in Germany, whose parents have been born elsewhere?

Best regards, Serhat