The regulation of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is a controversial topic across the EU, and member states have repeatedly failed to reach decisions on the issue. This deadlock led in part to a proposal by the European Commission in February 2017 to fundamentally change the EU’s comitology procedure, with new rules being established for votes in the Council of the European Union. Based on a recent study, Monika Mühlböck and Jale Tosun illustrate the factors that have shaped member states’ voting behaviour on GMOs. They show that voting behaviour has been significantly influenced by national factors such as public opinion, party politics, and structural as well as sectoral interests. But while different interests are well represented in the decision-making process, these interests cannot be reflected in the outcome (i.e. the authorisation of GMOs) as long as the final decision is referred back to the Commission for approval.

The regulation of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) is a controversial topic across the EU, and member states have repeatedly failed to reach decisions on the issue. This deadlock led in part to a proposal by the European Commission in February 2017 to fundamentally change the EU’s comitology procedure, with new rules being established for votes in the Council of the European Union. Based on a recent study, Monika Mühlböck and Jale Tosun illustrate the factors that have shaped member states’ voting behaviour on GMOs. They show that voting behaviour has been significantly influenced by national factors such as public opinion, party politics, and structural as well as sectoral interests. But while different interests are well represented in the decision-making process, these interests cannot be reflected in the outcome (i.e. the authorisation of GMOs) as long as the final decision is referred back to the Commission for approval.

Credit: DasUngesagte (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The authorisation for cultivation or marketing of GMOs (e.g. GM maize) in the EU is subject to the so-called “comitology” procedure, wherein the policy-making powers of the European Commission are controlled by the Council (sidelining the European Parliament).

Whenever an authorisation request is issued, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) is asked to review potential risks to human health and the environment. Based on the EFSA’s opinion, the Commission drafts a decision regarding the application, which is submitted to the Standing Committee on the Food Chain and Animal Health which is composed of representatives of the member states. If the Committee accepts the proposal by qualified majority (the current threshold is 55% of the member states comprising at least 65% of the EU’s population), it takes effect; if the committee rejects the proposal by qualified majority, it fails.

Yet, the member states’ representatives in the Committee have never been able to reach a qualified majority – neither in favour nor against. Prior to 2014, these decisions were thus forwarded to the ministers in the Council for a vote, but they have also consistently failed to take a decision. Since 2014, the ministers themselves are no longer directly involved, with the “Appeal Committee” (staffed by member state representatives) now in charge.

The outcome, however, has remained the same – namely, consecutive “no opinion” scenarios. In comitology procedures where the member states cannot reach a qualified majority within a certain period of time, the rules foresee that the proposal will be automatically adopted by the Commission. Due to the fact that member states are completely divided over this sensitive issue, GMOs have always been authorised by the executive (the Commission) without the support of the legislative (the Council). This poses a serious threat to democratic accountability.

At the same time, the disagreement between the member states presents a unique opportunity for scientific analysis. In general, Council votes are characterised by an extremely high level of consensus. The vast majority of votes are passed with all member states voting in favour. Even if there is dissent, it is usually only one or two member states voting against a proposal, as controversial proposals seldom reach the final decision-making stage, but rather tend to be revised in order reach a compromise. As a result, there is little variation in voting behaviour, thereby rendering it difficult to identify its driving factors. However, this is not the case with regard to GMOs.

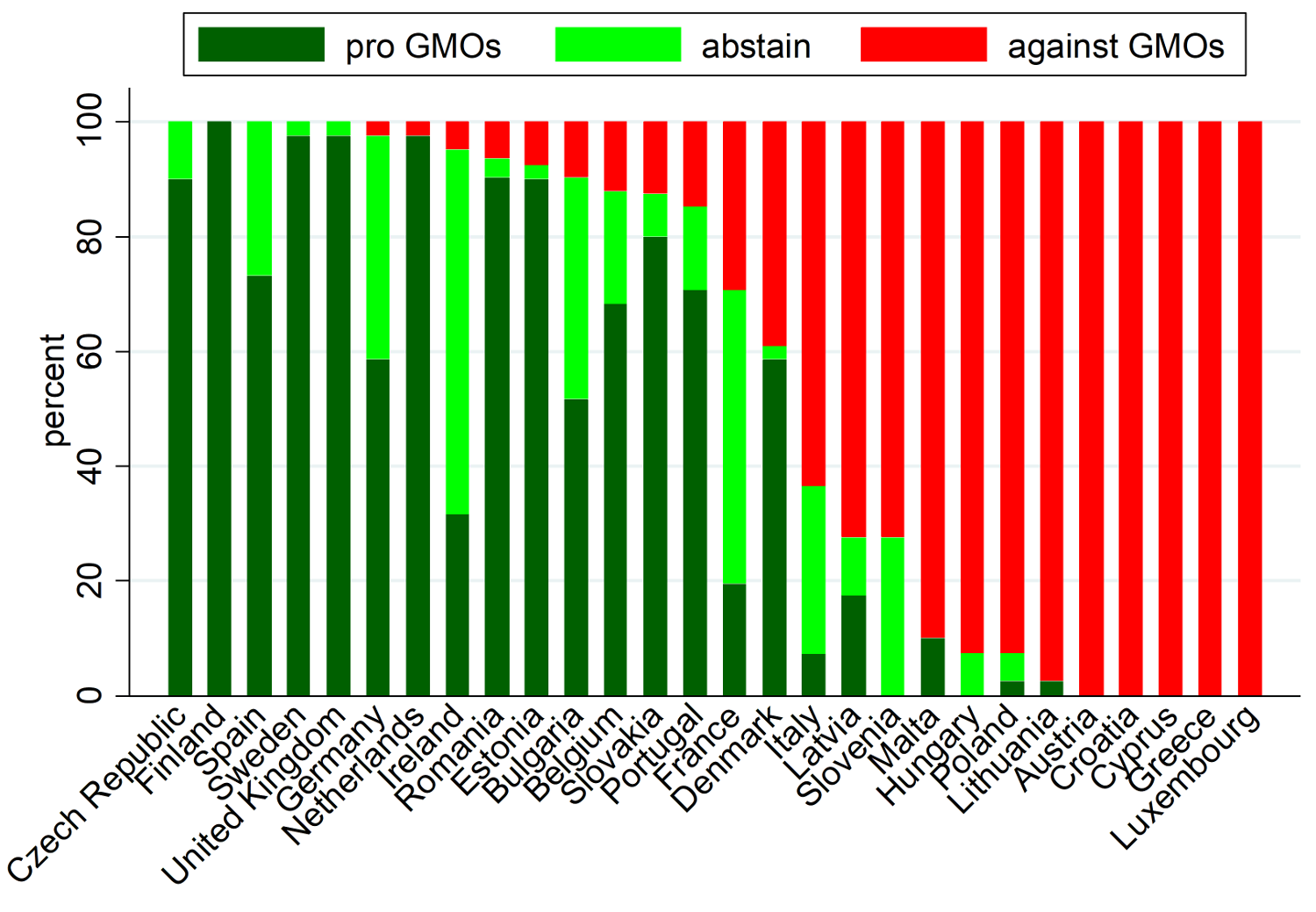

As the figure below shows, voting behaviour on GMO authorisation requests varies greatly between member states but also within member states over time. Essentially, there are two types of member states. On the one hand, there are those that have voted in exactly the same way on every authorisation request. This group consists of Austria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, and Luxembourg in the anti-GMOs camp, with Finland in the pro-GMO-camp. On the other hand, many countries display volatile voting behaviour, suggesting that national interests may change over time, for instance due to gradual shifts in public opinion (e.g. in France) or changes in the composition of governments (e.g. in Ireland), or may even vary on an issue-to-issue basis.

Figure: Positions of member states in the Council regarding GMO authorisation requests (2004-14)

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article in the Journal of Common Market Studies.

When testing which factors affect voting behaviour on GMOs, we observe a significant effect with respect to national public opinion. Ministers representing publics that are more concerned about the use of GMOs are less likely to vote in favour of authorisation requests. Furthermore, Council votes on GMOs are affected by the ideological background of ministers. For example, representatives from ecological parties have a higher likelihood of voting against the authorisation of a new GM product, whereas representatives from agrarian parties base their voting decisions on the structure of their country’s agricultural sector.

Although ministers have been shown to be responsive to national constituencies when voting on GMOs, the outcome of the entire process – i.e. the authorisation being granted by the Commission – is not democratically legitimised, as it is not based on the necessary level of approval, but simply on the absence of the necessary level of opposition. This is partly due to the fact that member states – even large ones, such as Germany – often cast abstentions. Abstentions are in effect a (softer) form of GMO approval, as they prevent the Council from reaching the necessary qualified majority to stop the authorisation process. At the same time, abstaining member states may deny responsibility by claiming they have not taken a decision.

The Commission’s proposal for revising the comitology system responds to these shortcomings by suggesting a new voting system where abstentions shall be ignored when calculating the qualified majority among member states. While this may provide a partial remedy, it seems unlikely that the proposal will be adopted in its current form. It does however hold the potential to spark new debates on the comitology process.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article in the Journal of Common Market Studies. This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Monika Mühlböck – University of Vienna

Monika Mühlböck – University of Vienna

Monika Mühlböck is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Economic Sociology at the University of Vienna. Her research areas cover EU decision-making, legislative behaviour, and labour market policy.

Jale Tosun – Heidelberg University

Jale Tosun – Heidelberg University

Jale Tosun is Professor of Political Science at the Department of Political Science at Heidelberg University. Her research interests cover European integration, sustainability, and labour market policy.

Hello. Congratulations to the authors for the in-depth analyses in their published papers, summarized here.

This is to let you know that I tried to give a comprehensive “Schumpeterian” interpretation of the whole story of the (anti-)”GMO” regulation in the EU (first reference hereunder) and a similar analysis of a peculiar case (second reference).

1. The EU Legislation on GMOs between nonsense and protectionism: An ongoing Schumpeterian chain of public choices, GM Crops and Food: Biotechnology in Agriculture and the Food Chain, January 2017, 8:35–51, http://www.tandfonline.com/eprint/byiSkebKvAVnYvhRTATt/full

2. Tagliabue, Giovanni [2016] “GMO” maize and public health – A case of Schumpeterian policy vs. free market in the EU. Bio-based & Applied Economics, 5(3):325-332, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13128/BAE-18510

webpage: http://www.fupress.net/index.php/bae/article/view/18510/19055

direct link to pdf download: http://www.fupress.net/index.php/bae/article/download/18510/19055