During the Brexit Referendum and subsequent elections in the US, Britain, France, Germany and Austria, questions have been raised about the role of social media, and in particular foreign involvement, misinformation, and lack of transparency. As Italy prepares for elections on 4 March, Damian Tambini examines the background and asks what academic and civil society election observers should be looking for.

During the Brexit Referendum and subsequent elections in the US, Britain, France, Germany and Austria, questions have been raised about the role of social media, and in particular foreign involvement, misinformation, and lack of transparency. As Italy prepares for elections on 4 March, Damian Tambini examines the background and asks what academic and civil society election observers should be looking for.

People are spending increasing amounts of time on social media. New advertising practices are emerging that are based on those of ‘surveillance capitalism’: gathering and linking multiple databases to build sophisticated profiles of voters and segment the voting population according to demographics and ideological preferences. This enables political parties and campaigns to target specific messages at specific voters.

There are multiple potential problems with this ‘targeted propaganda’, as we set out in a policy brief published last year, but because of a lack of transparency and reliable research, it is very difficult to separate alarmism and sour grapes from findings that might confirm that fairness and legitimacy of elections have indeed been undermined. Charges against targeted propaganda include claims that:

- Messages are not transparent because campaigns develop many thousands of different adverts including ‘dark posts’ that disappear after viewing. Parties distribute messages based on a sophisticated knowledge of what motivates the behaviour of individual voters, rather than developing a single clear message for all voters. targeted propaganda

- This targeting and opacity enables campaigns to avoid scrutiny: campaigns can therefore strategically target ‘fake news’ and deliberate misinformation, with intent to skew the electoral outcome.

- The process of targeting enables parties to focus resources on marginal groups likely to win the election, undermining the process of national deliberation and exacerbates fragmentation and ‘echo chambers’. This may be compounded by negative ‘attack’ campaigns

- The shift to social media campaigns renders obsolete much of the existing regulation which is designed to make campaigns fair and transparent, and facilitates foreign involvement through funding and provision of database services.

- All of these combine to undermine the fairness and legitimacy of liberal democratic elections as the Council of Europe has been examining.

These issues have arisen most prominently following the US election of 2016 and the Brexit referendum. In both cases there are ongoing investigations regarding whether illegal practices have taken place including data protection breaches, fraud, foreign involvement, and breaches of campaign finance laws. In particular, there have been widespread allegations of Russian involvement in fostering misinformation, nationalism and populism, in part through social media channels.

In the US, allegations of deliberate misinformation through social media form part of an investigation of Russian involvement in the 2016 election campaign. In the UK, the Information Commissioner’s Office and the Electoral Commission are investigating rule breaches in relation to data-sharing and election finance. As a result of these controversies, electoral campaigns since the referendum, which have taken place in the Netherlands, France, Germany and Austria, have been the focus of increased scrutiny. In those countries as well, there have been allegations, but no formal findings of legal breaches. During the French elections, Facebook was obliged to remove thousands of fake profiles which were disseminating fake news intending to sway the electoral result, and President Macron recently gave a speech in which he announced a new law providing for the blocking and removal of fake news and potentially penalties for disseminating it, during elections.

In Germany, and in the 2017 UK election, the issue of targeted propaganda and misinformation was arguably less prominent, and there have been few allegations. But academics, working with civil society groups such as Who Targets Me are monitoring such campaigns with a view to analysing how campaigns are changing, and what implications this may have for future regulation.

A number of academic and civil society activists have responded to different aspects of this new communication challenge. A group of hackers claiming to represent “Anonymous“ in Italy for example has pledged to fight against fake news bots. Researchers at the LSE are working with the Who Targets Me project – which increases transparency by asking volunteers to have their ad exposures tracked – and has monitored elections in the UK, Germany and Austria. Other projects like the Propublica, BaKaMo Social and researchers such as Phil Howard in Oxford have been monitoring misinformation and bot activity.

What is the background to this election?

Since the resignation of Matteo Renzi in 2016, Italy has been governed by a coalition led by his centre left party colleague Paolo Gentiloni. During 2017 there has been a general shift away from the established leaders and parties to ‘fringe’ parties. Polls indicate that the election is likely to be close, leading to an inconclusive outcome, but, in common with other elections in Europe there is a high level of voter volatility in the period since the European elections in 2014.

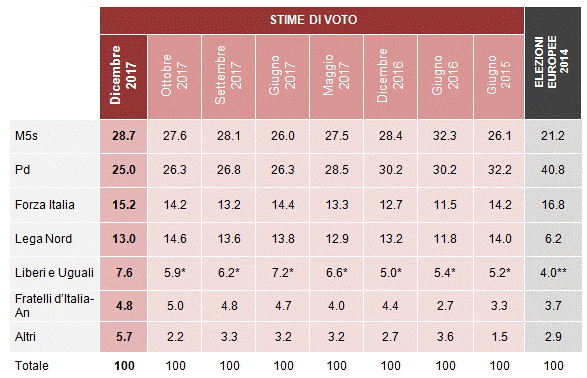

The table below from a Demos report shows a swing toward the Five Star Movement (M5s) which, with around 30% of the intended vote, would become the largest party in Parliament under Italy’s proportional system. Fringe parties such as Fratelli d’Italia have made ground (together with other small parties they make up 10%) of intended votes, and the Lega have made something of a comeback towards their 1990s peak, with 13% of intended votes. So, whilst the Five Star Movement look likely to emerge as the biggest single party, they may not have the seats necessary to form a government. The largest coalition is likely to be a right of centre group including Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and the (anti-immigrant) Lega.

Figure 1: Demos polling figures ahead of the 2018 Italian election

Source: Demos (Italy) December 2017

The issue of Europe is arguably one of the key opinion cleavages in the campaign. In part because the introduction of the euro coincided with a crisis in the Italian economy which was rapidly compounded by a global economic crisis, there is widespread mistrust of the single currency. A research team from Perugia and Torino University has compiled a list of the most resonant topics in the media so far. The proposal of a leading Five Star Movement politician for a referendum on membership, and his statements that he would like to leave the euro, have been gaining in resonance. Migration is also prominent as an issue, and recent challenges of integrating refugees have created some tendency for populist nationalist messages to gain relevance.

Italy’s electoral law is based on a proportional representation electoral system, and this has been associated with somewhat weak multi-party coalition governments. There is a large number of tiny fringe parties. Given dissatisfaction with the performance of the current government, these smaller parties may stand to benefit, but they have to get more than 3% of votes in order to take up their seats.

How many voters use social media?

The first thing to note about this election is that whilst it might appear that young people in Italy are glued to social media, they form a lower proportion of voters and this may diminish the role of social media in the vote. Data from 2016 suggest that internet access and use in Italy lags behind other media. While over 80% of people aged between 14 and 25 reported social media activity, this slopes off rapidly for those over 45 years of age. The percentage of those of voting age reporting social media activity is still around 50%. As a result, the potential impact of social media campaigning at this election is perhaps lower than in the UK, but even so, given the closeness of the election, the online campaign could swing the election.

Figure 2: Social media usage in Italy

Note: The author wishes to thank Sofia Verza and colleagues at the University of Perugia for highlighting this data.

Foreign interference?

If we cast Putin as the quintessential James Bond villain in his Kremlin bunker, what would he do if his objective was to destabilise Italy and Europe? The allegation with respect to the US election was that foreign actors supported extremist and fringe parties, and those most likely to sow discord. There is certainly ample potential for this. One of the allegations about foreign involvement in US politics has been that foreign actors are supportive of radical, populist ‘outsider’ movements in order to destabilise politics more generally.

This is perhaps the most worrying factor in the Italian case as polls since the last election appear to indicate a widespread perception that support for fascism is gaining ground. Almost half of Italians say that fascism is ‘widespread’ or ‘very widespread’ in Italy according to this report. Whilst respondents may differ in their definitions of who is a fascist, most will agree that fringe groups such as Forza Nuova fit the bill and there is growing support for such radical groups in the context of the ongoing migration crisis. It is worth noting on the other hand that Italian experts I have spoken with suggest that rumours of direct Russian involvement in the campaigns are disappearing.

There remains the potential for other actors to be involved. Investigative journalist Carole Cadwalladr has focused on the involvement of foreign companies in the provision of database services, which has benefits inclined to the official campaigns that should have been declared as electoral expenses. It is highly likely that it is the more invisible and expensive aspect of data-based profiling that impacts the Italian election. Very little is known about the approach to profiling by Italian political parties: international experts agree that maximising the data points involved in profile creation combined with sophisticated segmentation permits more efficient campaigning: in theory messages appropriate to a given demographic or opinion group can be targeted and timed to better effect if more is known about the profile of individual voters.

To sum up: it is certainly important to shine a light on social media and targeted campaigning as the election unfolds. It can be predicted with certainty that one commentator or another will say this is the ‘first Facebook election’ in Italy, but what that means, and whether this is necessarily bad news is not going to be immediately evident. It is impossible to predict if some of the controversies around foreign involvement and misinformation will be repeated in Italy.

What is clear is that election campaigning is gradually developing a targeted online dimension and this is displacing older modes such as broadcasting. How this develops, and the extent to which the two modes compete or coexist will depend on user behaviour and also on how quickly regulators can respond.

Damian Tambini, alongside colleagues at the University of Perugia, will discuss and debate these issues with international experts at a workshop on 16-17 February, sponsored by the Open Society Foundation.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credits: Palazzo Chigi, European People’s Party, European Parliament, Luca Argalia (CC BY-NC 2.0)

_________________________________

Damian Tambini – LSE

Damian Tambini – LSE

Damian Tambini is Research Director of the LSE’s Department of Media and Communications.