Corruption is still viewed as a key problem in many states across Central and Eastern Europe. Drawing on recent research in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, and Romania, Clara Volintiru, Bianca Toma and Alexandru Damian highlight the problem of political actors using resources from state owned companies to help win elections. They argue that a widespread lack of accountability in managing public resources is threatening the quality of democracy in these states.

Corruption is still viewed as a key problem in many states across Central and Eastern Europe. Drawing on recent research in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, and Romania, Clara Volintiru, Bianca Toma and Alexandru Damian highlight the problem of political actors using resources from state owned companies to help win elections. They argue that a widespread lack of accountability in managing public resources is threatening the quality of democracy in these states.

Faced with political turmoil, the new democracies of Central and Eastern Europe remain as vulnerable as ever to state capture and weakening accountability mechanisms. In January, the Czech Republic’s recently elected populist Prime Minister Andrej Babis lost the necessary vote of confidence faced by any incoming government, as other parties were hesitant to enter a coalition with him given his corruption indictment four months earlier.

Meanwhile, since winning elections a little over a year ago, the incumbent Social Democratic Party in Romania has reshuffled the government three times (on each occasion deposing its own prime-ministers in parliament) and has faced numerous protests over judicial reforms intended to roll back on anti-corruption efforts. The government’s recent calls to remove the country’s chief anti-corruption prosecutor have brought the EU’s focus onto the issue. Bulgaria is also struggling with the phenomenon of corruption, with the weaknesses of their new anti-corruption legislation taking centre-stage during its presidency of the Council of the European Union.

The picture that emerges from these cases is that electoral outcomes are increasingly generating instability in the region, with political crises becoming regular occurrences. These democratic crises are linked to issues of trust and accountability on the part of political parties. Processes of cartelisation coupled with the clientelistic distribution of public goods and services can improve the chances of a party surviving in office, but they do little to foster legitimacy or credibility. Furthermore, processes of state capture make political parties addicted to a continuous supply of public funds and resources.

Tapping into public resources: Political control over state owned enterprises

As part of a project entitled State-Owned Companies – Preventing Corruption and State Capture, we have evaluated the extent of state capture and the nature of mechanisms for extracting public resources for private or political interests in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Italy, and Romania.

State owned enterprises (SOEs) are an important vehicle for economic growth. From South Africa to Eastern Europe, they often constitute a ‘golden goose’ for ruling political parties. There are three main types of resources that a clientelistic political party could be interested in: public jobs, public contracts, and public finances. Given the extension of state owned enterprises in EU countries, low public scrutiny and their scattered distribution (local, regional, national), such companies are often easy targets for corrupt and clientelistic approaches.

Western Europe is currently pushing through reforms to accelerate market liberalisation and the competitiveness of the remaining state owned enterprises. In contrast, states in Eastern Europe have a greater tendency to use illiberal or nationalist discourses to ensure as much discretionary control as possible over their assets. If public contracts or public jobs are important for clientelistic distribution, very few institutions can rival the budgets of the largest state owned enterprises.

The ‘laggards’ or late comers of the European Union, Bulgaria and Romania, face numerous developmental challenges: from poverty to institutional weakness. Looking at such indicators as economic development at the regional level or minimum wages, one consistently finds them at the lower end of the EU rankings. Deeply connected to the developmental challenges of Romania and Bulgaria is the institutional corrosion of corruption. Nevertheless, over the last few years successful anti-corruption criminal investigations have been implemented in Romania, even if little has been done in the sense of prevention or recovery. Many domestic and international stakeholders see the anti-corruption efforts as a test of the EU’s positive influence in these two countries.

The resources of state owned enterprises are often used to fund political parties or electoral campaigns. Their resources mainly serve as ‘post electoral rewards’ for political backers, disrupting electoral cycles and hindering one of the key requisites of a democratic system: accountability. Discretionary use of national resources through state owned enterprises goes hand in hand with party patronage and a lack of merit based appointments.

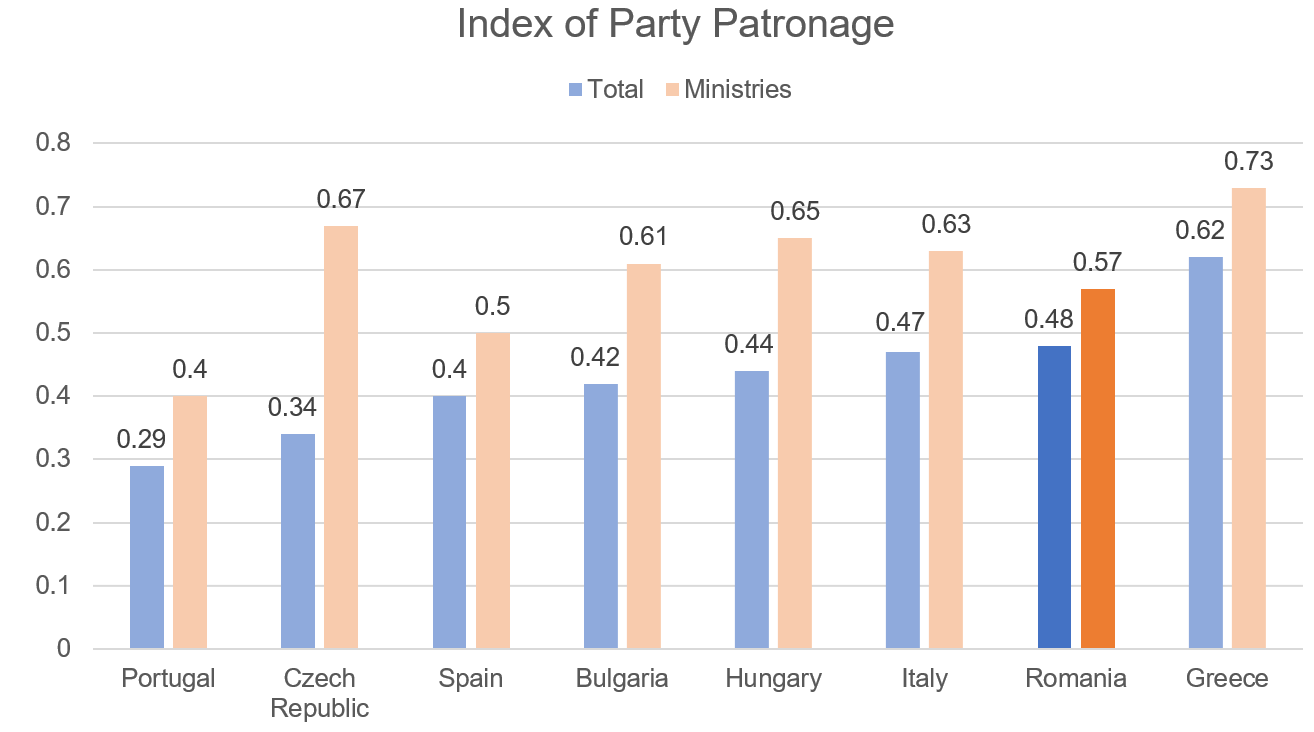

State owned enterprises in Romania, Bulgaria and the Czech Republic are ‘populated’ with politically appointed individuals, especially in the well-paid top positions. State owned companies in Romania offer no fewer than 877 positions on the Board of Directors, which are appointed by the State, and the monthly remuneration varies from approximately 1,000 euros to 30,000 euros. In a widely used index of party patronage (shown in the figure below), Romania has a worse ranking than Bulgaria and the Czech Republic when it comes to overall patronage, although the Czech Republic appears to be heavily politicised at the central government level. Party patronage is visibly more prevalent in Central and Eastern Europe than it is in other new democracies such as Portugal and Spain.

Figure: Index of party patronage (selected countries)

Source: Kopecky et al 2016, Volintiru 2015

High levels of politicisation can generate institutional instability. Research conducted by the Romanian Center for European Policies shows that, in the case of Romania, state owned enterprises have an average management duration of less than one year, with political changes/electoral cycles triggering changes in the management of state owned companies on almost every occasion. Similar political trends are present in the Czech Republic, where in the years leading up to elections, around 88% of the chairs of supervisory boards of companies owned by municipalities have been replaced.

The key challenge faced by state owned enterprises in Bulgaria is also political interference, as a recent analysis by the Bulgarian NGO, Risk Monitor, has shown. In Bulgaria, the only case in which a state company director has been charged and convicted of corruption (the director of the Toplofikacia Sofia EAD heating company serving the city of Sofia) was related to the influence of politics.

In the Czech Republic, accusations of political influence and corruption linked to state owned enterprises have close links with almost all the heads of government over the last ten years. This includes accusations over appointments to the supervisory boards of members of political parties, according to a study conducted by Candole Partners.

In Romania, well-paid positions in state-owned companies have been and will continue to be used either as rewards for political sponsors and their relatives, or as a way to supplement wages in the central public administration. Romanian anti-corruption prosecutors have shown how the resources of state owned enterprises have been involved in most electoral campaigns in recent years.

The Romanian presidential campaign of 2009 involved illegal funding in exchange for influence over high-level appointments at the most important and profitable gas companies, as well as the nomination of the Minister of Economy. In another case, the National Anti-Corruption Directorate is investigating fictitious advertising contracts signed by a state owned company covering costs related to the 2009 presidential campaign. At the local level, there are dozens of cases where illegal funding originating from public utilities procurement contracts have allegedly been used for election campaigns.

Why do we need accountability?

In Central and Eastern Europe, corruption and capture risks have yet to be mitigated. With the exception of Romania, which has a high number of criminal investigations, there has been a weak response by judicial bodies to discretionary control over state resources. According to our research, new European democracies suffer from inefficient preventive, control and auditing measures.

Without proper monitoring and sanctioning mechanisms in place, state owned companies and other public institutions are vulnerable to discretionary control. Public resources may essentially become private resources at the disposal of ruling politicians. The lack of accountability in managing public resources, be they jobs or funding, risks invalidating the social contract in these states. Some ruling parties in Central and Eastern Europe are no longer (and perhaps never were) doing the work of the electorate; rather they control wealthy public assets and have captured the resources they need to win elections through clientelistic methods, severely affecting the quality of democracy in these countries.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Clara Volintiru – Bucharest University of Economic Studies

Clara Volintiru – Bucharest University of Economic Studies

Clara Volintiru is an Associate Professor at the Bucharest University of Economic Studies (ASE). She has a PhD in Political Science from LSE and her recent research can be found in East European Politics, European Political Science Review (EPSR), or Research & Politics. She has been a consultant for international organisations such as the World Bank, European Commission, Eurofound, and the Committee of Regions.

Bianca Toma – Romanian Center for European Policies

Bianca Toma – Romanian Center for European Policies

Bianca Toma is Programme Director at the Romanian Center for European Policies and is involved in projects related to the judicial system, anti-corruption and state capture. She has over 15 years of experience as a journalist, including as a Brussels-based correspondent for Romanian media.

Alexandru Damian – Romanian Center for European Policies

Alexandru Damian – Romanian Center for European Policies

Alexandru Damian is a Researcher at the Romanian Center for European Policies. He is involved in projects related to foreign affairs, the Eastern Partnership, the judiciary and anti-corruption. He is a graduate of Political Science and has an MA in EU Studies from the Free University of Brussels.

It’s too bad that the studies discussed in this article did not include Poland, which has over 20% of GDP as market value if its SOE’s but employing in the SOE sector well under 2% of all employment – a situation ripe for exploitation. The PiS party has shamelessly captured the state and is blatantly using SOE’s to employ family, friends and supporters while using their resources to try to stay in power indefinitely. PiS are actually increasing the size of the SOE sector by renationalising banks and other enterprises. A study of Poland in this context would be timely.

Thank you for the input. A follow up on this study will, most likely, include Poland due to the high number of SOEs and their importance in the economy (some of them holding monopolies or acting as key crucial players). And, yes, the correlation between the political power in Poland and the SOEs seems somehow similar to other CEE countries and would be of high interest to see some state capture patterns also.

There is a bad factual error here, which needs correction. Andrej Babis did not lose a vote of no confidence in the Czech Republic in January. He failed to win a vote of confidence for his newlyformed government. He resigned because he is obliged to do under the Czech Constitution. He had no option to do so and such a resignation He certainly has poblems with a corruption indictment which have contributed to his difficulty forming a coalition, but has so far faced them down

I am interested by the parallels between the situation that you describe and that of the ‘corporate state’.

Revolving doors, cooperate appointments to public sector bodies, patronage dispensed via the award of public service contracts, visible and oblique party political donations and objective growth impediments felt either in terms of market distortions owing to the neutralisation of collective bargaining, low wages or poor productivity.

At UK BUIS, much legislation is prefigured in ministerial salons which tend to be dominated by the big 3. In essence, there are striking similarities between state and private sector political capture.

I dare say that there is a Phd waiting to be written.