With A Brief History of Feminism, Antje Schrupp and illustrator Patu have crafted a graphic novel that traces the development of feminism from antiquity to the present day. While the book is primarily limited to offering an account of the evolution of European, Western feminist movements, this is nonetheless a fun, accessible and educational read that will give readers a thirst to learn more, finds Sonia J. Wieser.

This review is published as part of a March 2018 endeavour, ‘A Month of Our Own: Amplifying Women’s Voices on LSE Review of Books’. If you would like to contribute to the project in this month or beyond, please contact us at Lsereviewofbooks@lse.ac.uk.

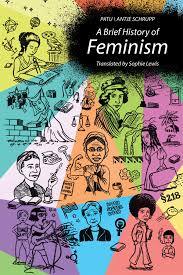

A Brief History of Feminism. Antje Schrupp, illustrated by Patu (trans. by Sophie Lewis). MIT Press. 2017.

In times of the Women’s March, the #metoo revelations and the subsequent widening of the discussion around women’s rights and gender equality, the sheer number of available texts on the history of the evolution of this movement can be overwhelming. With their collaboration on A Brief History of Feminism, author Antje Schrupp and illustrator Patu have crafted a comprehensive graphic novel that takes the reader on a journey to discover the development of feminism from antiquity to the present day. It will leave you feeling entertained and educated, but at times also angry and definitely thirsting to learn more.

Unlike other books on feminism, this ‘brief’ history does not take women’s struggle to gain the right to vote as its starting point. With the main focus on European, Western feminism, it starts out in antiquity with references to Ancient Greece and the early days of Judeo-Christianity. It continues through the Middle Ages and the first records of women-led community life, early-modern feminism and the feminism of the Enlightenment. While these periods might not offer the widest choice of substantive texts of which it can be said with certainty that they were authored by women, tracing the evolution of feminism alongside that of patriarchy only makes sense.

The chapters become more substantial as the book turns to discuss early socialist feminism, the beginnings of an organised women’s movement, women’s wage labour and the struggle for women’s right to vote. The book continues on to chapters around sex and gender, autonomous women’s movements, and ends by dedicating short sections to intersectionality, queer feminism and third-wave feminism.

Image Credit: (Trishhhh CC by 2.0)

Image Credit: (Trishhhh CC by 2.0)

This comprehensive and artfully illustrated view of the history of feminism makes the book a really good read for anyone, no matter whether they are previously acquainted with the movement or not. A reader new to the topic gets an introduction that is fun and conducive to wanting to know more; the reader that is an expert will be delighted to find women ranging from Flora Tristan, who wrote about the oppression of the working class before Karl Marx, to Shulamith Firestone, who argued for the total abolition of the biological family in the 1970s, being placed under the spotlight.

Another incredible strength of this book is that it works with relatively few textual explanations of the illustrations. While the individual chapters offer brief introductions to set the context, most text is limited to the dialogues between the protagonists. This allows for an additional dimension to the story, as facial expressions, colloquial wording and the environment surrounding the speaker underline the content of what is being said. And this is especially important in the context of the oppression of women, as it is often that this is not performed through mere brute force, but more subtle means. For example, the book depicts an exchange between Mary Magdalene and Jesus, in which she questions the maleness of Jesus’s inner circle. Jesus responds, ‘Really, Mary, do you always have to be so negative?,’ while rolling his eyes (2).

While the aforementioned strengths make reading this book a fun and educational experience, the book also comes with certain weaknesses. It lacks a clear guide for the reader as to when the text is paraphrased to fit the style of a graphic novel or when it is directly quoting from a text. Given this, it is also unclear what sources the authors used for their research for their book. While excluding a bibliography or footnotes in the text might have been a conscious decision by the creators to keep the feeling of a graphic novel, it makes it much harder for an interested reader to pursue specific further reading. Furthermore, in times of harsh criticism of ‘feminism’ as a concept and the constant questioning of sources as ‘fake news’, a book may fare better if it is clearly shown on what basis it was written.

A space within the book that would be conducive for this guidance would be the introductory text. Already offering a great explanation of why the history of feminism matters and what it has to do with patriarchy, it also provides an opportunity for the authors to delve deeper into how to read the book and their thoughts on the sources. In so doing, they could also connect the introduction to the rest of the book more than is currently done.

A further point of criticism that could arise is the text’s sole focus on European, Western feminism. Some context to this lies in the somewhat limited translation of the title: in its original German version, the book is explicitly called ‘A Brief History of Feminism in the Euro-American Context’; this is reduced to only ‘A Brief History of Feminism’ in the English translation, which could lead a reader to expect equal treatment of all women’s movements across the globe. The authors do, however, make the limited scope of the book fairly clear in the introduction of the book. Furthermore, various chapters touch upon the fact that European, Western feminism is not the only important movement: as such, the book briefly discusses intra-feminist socio-economic divisions, mentions intersectionality and nods to further exploration of third-wave feminism.

Again, the graphic novel adds a layer here: the intra-feminist divide along socio-economic lines is underlined by images depicting women of colour speaking up against the dominance of white women in the agenda-setting of feminist movements. The authors furthermore try to be as fair to the topics as possible: as such, they do mention that when discussing intersectionality, one has to pay close attention to the cultural context in which the discussion is founded. For example, they mention that due to the history of the civil rights movement in the US, the interplay between race and gender looks different in the US-North American context than, for example, in Europe. However, in the end, while the authors try their best to include various feminist movements and clearly mention the scope of the book, it is still a limitation – and one that one would wish was less prevalent in books about feminism in general.

Overall, while this book is restricted to European, Western feminism and arguably lacks some signposting for the reader, it is still strongly recommended to anyone who wants to know more about where some of the ongoing struggles in the name of feminism are rooted. Its style makes it an easy introductory read for those newly interested in the topic and enjoyable for those who already know a bit more. One can only wish that further editions including other elements of the history of feminism will be published, so that the pleasure of reading works by Schrupp and Patu is prolonged.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article is provided by our sister site, LSE Review of Books. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Sonia J. Wieser

Sonia J. Wieser is a graduate in MSc International Relations from the LSE and works at the intersection of finance and technology. She particularly enjoys reading and reviewing books about feminism and gender studies, critical approaches to work and technology as well as anything related to Russia and India.

Find this book:

Find this book: