Parliamentary elections will be held in Hungary on 8 April. Theresa Gessler and Johannes Wachs preview the vote, noting that although the governing Fidesz party has a sizeable polling lead, the contest promises to be closer than the last parliamentary election four years ago.

Parliamentary elections will be held in Hungary on 8 April. Theresa Gessler and Johannes Wachs preview the vote, noting that although the governing Fidesz party has a sizeable polling lead, the contest promises to be closer than the last parliamentary election four years ago.

Hungary has emerged as a trendsetter for Europe’s populist right. As Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party seeks a third consecutive term on 8 April, populist politicians from Italy, France, and Poland cite him as their prototype. Despite its membership in the European People’s Party, the party and its leader have become icons of the alt-right with their anti-Brussels and anti-refugee rhetoric. At home, Hungarian political discourse is following a worrisome trend: while four years ago Fidesz campaigned primarily on its utility-fee reductions, albeit in nationalistic terms, the current campaign has taken on a tone of civilisational crisis. Prime Minister Orbán frames the issue of refugee resettlement as a clash of civilisations.

Though Fidesz holds a commanding lead in the polls and is aided by a fragmented opposition, the election promises to be closer than the one four years ago. While many Hungarians support tough policies on migration, a majority of the electorate are dissatisfied with the general direction of their country. Healthcare and political corruption, not migration, are cited as primary concerns by wide margins. The 2018 election may also mark a change in the pattern of competition since the political environment has also changed: Fidesz has become more populist and right-wing and Jobbik has attempted to reinvent itself as a mainstream party. While the left is as disorganised as ever, there is momentum towards electoral cooperation in individual districts.

The parties

In previous years, Hungarian politics has been characterised by a polarised competition between two camps: Fidesz and everybody else. On the right, Fidesz absorbed its competitors over the course of the 1990s and 2000s. The exception is Jobbik, which first entered the parliament in 2010 and traditionally positioned itself to the right of Fidesz. Though Fidesz has always presented itself as the reasonable party between Jobbik and parties on the left, Fidesz has moved to the right, adopting many of the positions Jobbik set forth in 2010.

In contrast, the left of the political spectrum is fragmented. Since the 2006 re-election of the socialist-liberal government, no left of centre parties have won any significant elections at the local, national, or European levels. As a whole, the opposition has progressively fragmented into smaller parties, several of which are led by former officeholders of the socialist party (MSZP), including the former Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány’s Democratic Coalition (DK).

While these parties position themselves as alternatives on the left, the new electoral law, written by Fidesz after 2010, awards a majority of seats using the first-past-the-post system in electoral districts. In 2014, opposition parties received 55% of the popular vote and only 33% of the seats in parliament. Given the strong incentives to at least form an electoral alliance, only two parties have maintained their electoral independence in the past: Jobbik and LMP, a green party whose name means “Politics can be different”.

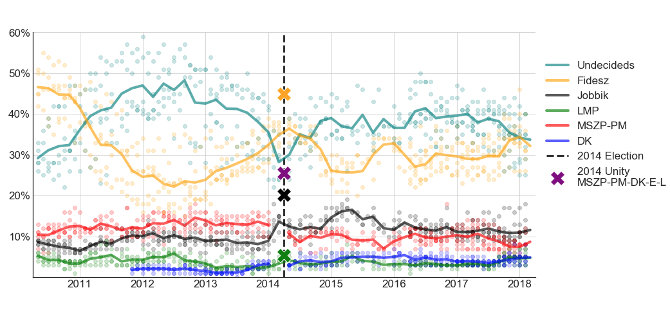

Figure: Hungarian polls since the 2010 election

Note: The chart shows polling of all Hungarian voters since the 2010 election, with the 2014 election results for the four main parties shown as an X. Shortly before the 2014 election, several opposition parties formed an alliance. The chart excludes several parties who are consistently far from the 5% electoral threshold (Momentum, Együtt, Liberals). Source: kozvelemenykutatok.hu

The polls predict more of the same: Fidesz has held a safe plurality in the polling since the last election. Yet the large mass of undecided voters leaves room for a surprise. Many Hungarians are dissatisfied with the government and its management of the country. In a recent poll, 76% of Hungarians said their country was heading in the wrong direction, a number that has been consistently high over the last few years.

A corruption scandal involving EU funds and the Prime Minister’s son-in-law has been the focus of opposition media for some time now. Good headline numbers on unemployment and the economy have not translated into broad social satisfaction. A recent mayoral election in the traditional Fidesz stronghold of Hódmezővásárhely shows the potential of this discontent: Péter Márki-Zay, an independent candidate supported by all opposition parties, defeated the heavily favoured Fidesz candidate. Tellingly, Fidesz’s candidate received a similar count of votes as four years ago: the difference came down to a large increase in turnout. This surprise victory has given new impetus for the opposition to cooperate.

Competition shifts to the right

Prior to the election, political competition has shifted further to the right, particularly on cultural issues. The start of the most intense phase of Hungarian parliamentary politics is traditionally the 15 March national holiday. Party leaders address their supporters and frame the primary issues of the campaign to come. These speeches provide insight into how the parties tailor their message to the campaign and how they evolve from election to election.

In 2014, Prime Minister Orbán dedicated his speech to praising the country’s unity and economic progress, and highlighting the need to support families to head off demographic challenges. Though many of the policy solutions had a nationalistic undertone – e.g. the scheme to help so-called “victims of foreign exchange loans” – the campaign was based on promising economic benefits to various social groups under the slogan “Hungary is doing better”.

The contrast with 2018 could not be stronger: Orbán’s speech this year focused entirely on the alleged dangers posed by migration. The speech warned Hungarians that migrants are threatening to take away the country – a sentiment that is mirrored in the rest of the Fidesz campaign. Running under the slogan “For us, Hungary first”, echoing Trump’s “America First”, Fidesz claims that a network of actors including the EU, “international speculators”, opposition parties, NGOs, and professional activists led by George Soros threatens the future of Hungary. Should this network defeat Fidesz and enable migration to Hungary, Orbán claims that the result would be like another Trianon, the treaty in which Hungary lost two thirds of its territory after the First World War. The government’s control over most major media outlets also means news reporting has prioritised migration.

This shift can be interpreted as a strategic reorientation of Fidesz. Given the continued fragmentation of the left, Jobbik has maintained its position as second strongest party. While some commentators have alleged a silent partnership between Jobbik and Fidesz in the past, Fidesz is now increasingly competing for voters on the right rather than in the centre. Mobilising some of Jobbik’s core topics such as immigration and hostility against Roma have been clear steps in this direction, particularly since all parties except Jobbik had avoided the Roma issue in past electoral campaigns. Indeed, in a recent campaign event Orbán made an analogy between the settlement of Roma in Miskolc and the threat of refugee resettlement.

In contrast, Jobbik has employed the opposite strategy and to some extent traded places with Fidesz. Since the migration crisis, Jobbik has increasingly focused on economic issues, advocating EU-wide minimum wage regulation. In the past year, the party has focused on political corruption, labelling Fidesz politicians as thieves on billboards around the country. Interestingly, many of these billboards are financed by Lajos Simicska, a former friend of Orbán and, until 2014, a key supporter of Fidesz. Jobbik’s orientation towards the opposition was also strengthened by a large fine imposed by the State Audit Office, which is led by former Fidesz MP László Domokos, that threatened Jobbik’s ability to run in the 2018 election and increased their criticism of the Fidesz government as undemocratic.

Electoral cooperation on the left: Will they, won’t they?

Given the strong position enjoyed by Fidesz in the polls and the heavily majoritarian electoral system, all opposition parties agree on the practicality of some kind of electoral cooperation. The current law, which was written from scratch by Fidesz following its landslide victory in 2010, favours large parties over coalitions: 106 seats are awarded as first-past-the-post to individual candidates in the electoral districts, and the remaining 93 seats are awarded proportionally to party lists. Many other details of the law favour Fidesz.

Though personal animosities among the opposition have majorly curtailed electoral cooperation, there are also substantive barriers to cooperation. As the electoral law prescribes a multiplication of the threshold if parties run with a joint list, it is relatively unattractive for opposition parties to formally combine their lists. Additionally, a recent decision by the National Election Committee forces parties to withdraw their party list if the party does not field a sufficient number of candidates in individual districts. Thus, parties endanger their national list (and thereby their entry into parliament) if they withdraw too many candidates in favour of other opposition parties.

The MSZP, Hungary’s post-communist centre-left party, has had a bumpy campaign and is no longer the obvious leader of a coalition, even on the left. The party’s first candidate for Prime Minister, László Botka, withdrew his candidacy in October, accusing parts of the party of collusion with Fidesz. Perhaps recognising its weakness, the party nominated Gergely Karácsony, mayor of a Budapest district and leader of a smaller opposition party (Dialogue for Hungary – PM) as a joint candidate. MSZP-PM and DK, another significant force on the left, have coordinated their candidacies in all districts. Though voters will be able to vote for either party list, only one party’s candidate will be present on the ballot in each district. Collaboration between this coalition and LMP, Momentum, and Jobbik, the remaining significant parties, has been much more limited, though there is still time for tactical coordination.

These efforts seek to replicate the Hódmezővásárhely formula for success: a single opposition candidate and high turnout. Though there will be several opposition candidates on the ballot in most districts, widespread tactical voting for individual candidates bodes poorly for Fidesz. Voters reluctant to support leading opposition candidates from another party can be consoled by voting for their preferred party on the list ballot. The idea of a united opposition has also found civil society support. Beyond the opposition parties, an activist group called “The Country is for All Movement” has commissioned a series of polls to determine the most promising opposition nominees in competitive electoral districts. Together with Péter Márki-Zay, the new mayor of Hódmezővásárhely, the group has created a list of what it views as the opposition candidate (including Jobbik) with the best chance to defeat Fidesz.

Yet there are several reasons to be sceptical about the potential of this approach. Convincing voters to cast ballots tactically is not easy. In nearly all districts there are still multiple opposition candidates. Even if agreements to withdraw candidates are reached, the chosen candidates will have much less time to campaign on their own (i.e. as the sole alternative to the status-quo) than Márki-Zay did. Finally, it is worth noting there are significant financial incentives for parties to field certain numbers of candidates: for instance if MSZP-PM steps back in four more districts (in favour of LMP or Jobbik), they would stand to lose half of their public funding. It seems unlikely parties will withdraw candidates when it means losing such a significant amount of money.

Can Fidesz be defeated?

The possible outcomes can be framed in terms of the two ways seats are awarded: by individual district mandates and party lists. In the first case, Fidesz’s outcome depends on the extent to which the opposition can coordinate, either by explicitly withdrawing lesser candidates or encouraging tactical voting. In the second case, high turnout will favour the opposition on account of Fidesz’s long incumbency and broad dissatisfaction among the electorate. Indeed, the Fidesz campaign is rallying its core voters, not making converts.

If opposition coordination does not materialise and turnout is low (in 2014 it was 62%), Fidesz may win another two-thirds majority. If coordination and tactical voting are effective and turnout is high (in 2002 it was 70%), Fidesz’s majority would be endangered. Popular candidates can go a long way in this – in Hódmezővásárhely, turnout increased by 26%. An intermediate outcome is most likely, where Fidesz will be able to govern alone for another four years, though without a two-thirds majority. In fact, Fidesz has already lost the two-thirds majority it won at the last election due to losses at by-elections during the legislative period.

As populist parties enter government in multiple European countries, Hungary is a useful example to study. Importantly, Fidesz has not moderated over time. As its power is threatened, it has abandoned economic themes and doubled-down on nationalist themes. It has further expanded the polarising logic of competition between party camps within the country to a wider conflict between Hungary and the EU. Consequently, international attempts to intervene when laws violate European regulations are framed as hostile actions against the country.

Fidesz was quick in changing the institutional framework of Hungarian democracy and other countries like Poland have followed some of these reforms – in turn these changes could have a large impact on political competition in these countries. In sum, the 2018 electoral campaign shows how defeating populists becomes more difficult as they consolidate their power. However, it also shows that voters remain sensitive to the performance of the political system and dissatisfaction can be mobilised by the opposition.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Theresa Gessler – European University Institute

Theresa Gessler – European University Institute

Theresa Gessler is a PhD Candidate at the European University Institute. Her research investigates how parties across Europe speak about democracy and the political system. She tweets @th_ges

–

Johannes Wachs – Central European University

Johannes Wachs – Central European University

Johannes Wachs is a PhD Candidate at Central European University’s Center for Network Science and a Researcher at the Government Transparency Institute. He researches corruption and collusion in public contracting markets. He tweets @johannes_wachs