Many Bulgarians have moved to the UK since the early-2000s, but as Maria Koinova notes, little research has been conducted on their views on life in Britain. Drawing on a new survey of Bulgarians in London, she writes that the Bulgarian community is notably different from the way it has been portrayed in the British media. It has many highly educated people, as well as low-skilled migrants, and most of them are employed. There also appears to be no excessive worry about individual prospects after Brexit, although Bulgarians in London report increased discrimination, and are aware that life outside the capital may be more challenging for other Bulgarians.

Many Bulgarians have moved to the UK since the early-2000s, but as Maria Koinova notes, little research has been conducted on their views on life in Britain. Drawing on a new survey of Bulgarians in London, she writes that the Bulgarian community is notably different from the way it has been portrayed in the British media. It has many highly educated people, as well as low-skilled migrants, and most of them are employed. There also appears to be no excessive worry about individual prospects after Brexit, although Bulgarians in London report increased discrimination, and are aware that life outside the capital may be more challenging for other Bulgarians.

On 3 May, researchers associated with a project of the London Bulgarian Association presented at the London municipality a ‘first of its kind’ survey of Bulgarians in the global city. The research was sponsored by a citizens-led initiative of London’s Mayor, Sadiq Khan, and featured results from a peer-researched (non-representative) survey conducted between March and April 2018. This project aspired to give a clear picture about a little-known community in the UK, which has attracted unfavourable attention in the British media, most notably surrounding the UK referendum on EU membership in 2016 and its aftermath.

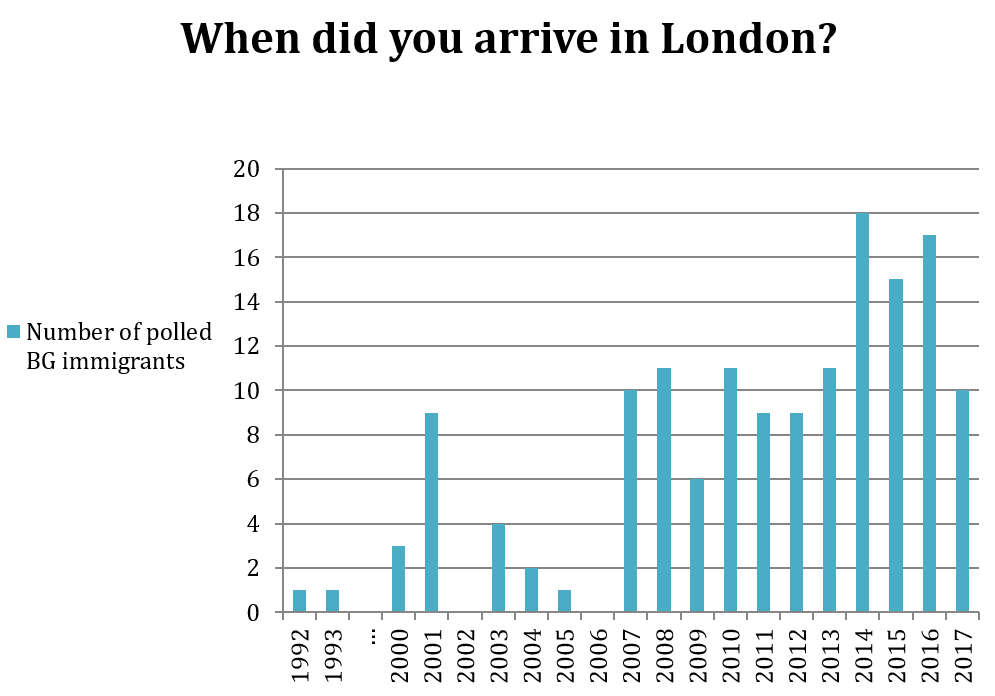

Bulgarians started migrating in significant numbers after the end of the Cold War in 1989. Major migration destinations became the US, Canada, Spain, Germany and other countries in Western Europe, with the UK favoured mostly in the new millennium. Data from the 2018 London-based survey illustrates this trend. As the figure below shows, the Bulgarians currently living in London mostly arrived recently, with few arriving before the 2000s.

Figure: Timing of migration of Bulgarians in London

Note: Figure is based on data from a co-authored study. The other authors were Boyko Boev, Dean Bezlov and Maria Stoilkova.

Three important policy developments impacted on the migration patterns of Bulgarians arriving in the UK. The first one was a 2001 UK migration policy allowing them a liberalised access to working visas under employment programmes and business projects. Another policy in 2002 established a selective opening of the UK market and created separate conditions for citizens of Bulgaria and Romania. The policy put Bulgarian and Romanian migrants into a distinct category (A2), thereby effectively separating them from other migrants from Eastern Europe (A8) whose countries entered the EU in 2004.

Bulgaria and Romania became EU members three years later. Bulgaria’s 2007 EU accession was followed by another migration wave, particularly in the mid-2010s, coinciding with the global financial crisis. Some Bulgarians previously employed in other countries severely affected by the crisis, such as Greece, Malta, Spain, Italy and France, moved to the UK. In the aftermath of the 2007 EU accession, a third policy lifted visa regime restrictions and regulated access to the UK’s borders, yet retained restrictions on the labour rights of Bulgarians and Romanians under the A2 status until the end of 2013.

These selective immigration policies exerted a significant influence on the image of Bulgarians and Romanians in the British media, motivating exclusivist public views of these communities. The typical media portrayal has been one focused on high crime rates among Bulgarians/Romanians and their exploitation of the benefits system.

The 2018 survey of Bulgarians in London challenges such stereotypes. First, among the sample of 151 people interviewed, only 4 respondents gave their status as unemployed, with half of them being employed full time, some of them – especially those in their 30s – working a second job overtime, and the rest being self-employed or working part-time. A wide range of jobs were reported, including high-skilled jobs such as IT specialists, analysts, programmers, engineers, university lecturers, teachers, marketing and public relations coordinators, accountants, sales representatives, designers, tax specialists, construction managers, photographers, dental practitioners, and students attending London universities, among others. Low-skilled jobs were also present, typically those related to cleaning and housekeeping services and care-provision, mostly among women; as well as car-mechanics, chefs, construction workers and stage workers in the theatre, which were typical jobs for men.

Younger immigrants – especially in their 20s and 30s – have experienced few problems finding a job, especially with regard to their qualifications acquired in Bulgaria or through additional education in the UK. There is an unfortunate trend, however, concerning Bulgarians in their 40s and to a certain degree in their 50s: many have university degrees, but have taken jobs below their qualifications. For those who arrived prior to 2004, it was difficult to get their diplomas and previous job qualifications from Bulgaria recognised in the UK. In line with a trend pervasive for most respondents in this sample, Bulgarians sought to adapt to their new life circumstances, and oftentimes to overcome challenges of emotional separation from family, as well as to learn the English language. Precarious work (working part-time or for several employers on odd jobs simultaneously) was visible especially among those in their 20s and 60s, with people in other age cohorts, who are the most productive in the work force, enjoying more stable employment.

Guests at a ‘Day of Bulgarian Culture’ in London on 24 May 2018, Credit: Tsanka and Borimir Totev (Reproduced with permission)

There are other trends in the data. Over 100 respondents declared that they felt happy in London, and in the specific borough in which they live. Some saw criminality as rising and cited violent incidents in their neighbourhoods, but they were a minority among those interviewed. A majority reported that living in London felt secure and had transformed them for the better, making them more tolerant, patient and productive individuals, even if they were more stressed due to the busy life in a global city.

The older respondents were, the more likely it was that they had migrated prior to 2014 and that they did so to join family. They were also more likely to have experienced issues with adaptation, especially with mastering English, to have maintained deeper contact with their neighbours, and to have had more critical messages about London as a busy city. Bulgarians of all age cohorts were unlikely to join associations, but were more likely to visit the gym regularly (up until their 50s), or to enjoy London’s cultural life of cinema, performances, concerts and theatres, especially among the more affluent respondents.

Bulgarians in their 20s were most motivated by a desire to explore the world and study; while those in their 30s were busy implementing their knowledge in the work place. Bulgarians in their 40s were typically seeking to both enhance their professional opportunities, and take care of families; those in their 50s sought to secure their financial future by sometimes seeking to pay off loans, gather funds to start a business or buy a place in Bulgaria; and those in their 60s were most interested in joining or staying together with their families.

The most unexpected results came from how Bulgarians in London reported their experience with Brexit. The majority were not excessively worried about their own prospects. Some stated that they were already British citizens and that Brexit would not affect them significantly. Many others had not been contemplating a change of plans, even if they anticipated that the most important challenges still lay ahead. There is no specific other migration destination on the minds of those who are contemplating leaving: some considered moving to Bulgaria, others to Germany, others back to the places in Southern Europe where they came from previously, and some were also considering Canada and the United States.

Women worried more than men about Brexit, as they saw more clearly the effects of rising prices, increasing inflation, and the discomfort triggered by a heightened sensitivity towards migrants. On the whole, however, people from the entire sample reported a rise in discrimination after Brexit, whether explicit or tacit, as well as awareness that London is not the entire UK, and that the life of migrants associated with Brexit might be more difficult outside the capital.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article is based on a co-authored study. The other authors of the study are Boyko Boev, Dean Bezlov and Maria Stoilkova. The article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Maria Koinova – University of Warwick

Maria Koinova is a Reader in International Relations at the University of Warwick and Chair of the British International Studies Association Working group on the International Politics of Migration, Refugees and Diasporas.