There has been a tendency in recent decades to strengthen institutions of metropolitan governance and planning in European cities, with large cities like London and Paris being viewed as primary drivers of economic growth. John Tomaney and Niamh Moore-Cherry highlight that one notable exception to this trend is Ireland and the city of Dublin. They explain that although Dublin dominates the national economy, a strong rural bias in Irish politics has combined with clientelism and centralisation to fuel dysfunctional urban and regional planning.

There has been a tendency in recent decades to strengthen institutions of metropolitan governance and planning in European cities, with large cities like London and Paris being viewed as primary drivers of economic growth. John Tomaney and Niamh Moore-Cherry highlight that one notable exception to this trend is Ireland and the city of Dublin. They explain that although Dublin dominates the national economy, a strong rural bias in Irish politics has combined with clientelism and centralisation to fuel dysfunctional urban and regional planning.

Across Europe, large metropolitan regions are now regarded as the principal drivers of economic growth. Key sectors, major firm headquarters and the accumulation of wealth are concentrated in large urban areas, typically capital cities. The promotion of large city-regions has emerged as a central policy concern for governments. Governance reforms have tended to reinforce the importance of the metropolitan scale in the planning of land-use, infrastructure and public services. But this process has been uneven between countries. In a recent paper we chart the failures to reform metropolitan governance in the Dublin region and the resultant consequences of dysfunctional urban and regional planning that marked the rise, fall and aftermath of the Celtic Tiger – the extraordinary period of rapid economic growth in Ireland that ended with the global financial crisis of 2008.

The European Commission has shown that, from 2002-2012, population growth in capital metro-regions was more than double the EU average. This growth was driven mainly by positive net migration, a higher share of working-age population and skilled workers, and a lower share of people aged 65 or over. Migrants from other EU regions and outside the EU were more likely to settle in capital cities. A large body of academic research has stressed the importance of effective urban and regional planning and well-functioning metropolitan governance in creating the conditions for sustainable development and improvements in the quality of life. As the OECD notes:

As the purview of spatial planning expands to address ever-wider objectives such as economic development and environmental/social equity, a broader metropolitan scale has been adopted in many countries. This is driven by the need for spatial and land-use planning to keep pace with functional territorial boundaries – the places across which people live, work and commute and the interacting ecosystems and geographies.

Consequently, there has been a tendency in Europe to create or strengthen institutions of metropolitan governance and planning. Examples include the creation of the Mayor of London, the Métropole du Grand Paris, Region Hovenstad in Copenhagen and Àrea metropolitana de Barcelona.

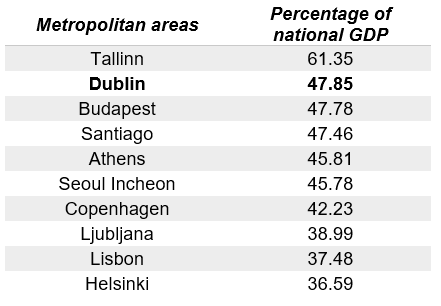

Ireland has tended to stand apart from these broader European trends. Dublin lacks a metropolitan tier government and reform efforts, to date, have failed. Why? Dublin dominates the national economy, as shown in the table below, but occupies an ambivalent place in Irish political geography. Irish nationalism was founded on an agrarian ideal and land reform claims. It also privileged the Gaelic origins of national identity, associated with the rural west. Dublin attracted suspicion as the centre of British colonial power, even if the 1916 Easter Rising took place on its streets.

Despite urbanisation, Irish politics contains a strong rural bias. The Irish state has never had a ministry for urban affairs but recreated a Ministry of Rural Affairs in 2017. The marginalisation of the urban has interacted with two other features of the Irish polity. First, Irish politics has rested heavily on clientelism rather than the kinds of ideological politics typical elsewhere in Europe. Second, Ireland is marked by a high degree of governmental centralisation, with few powers and little financial autonomy afforded to local government. Local government’s chief power is control of land-use zoning, which interacts with clientelism in unhealthy ways.

Table: Top ten ranking of OECD cities as a percentage share of national gross domestic product (2012)

Source: OECD Metropolitan Database

During the Celtic Tiger years, the local planning system, weak local government and traditional attitudes to land-ownership, constituted a critical component of the system of clientelism that served both individual voters seeking one-off housing and developers seeking large-scale residential and commercial schemes. A property-based growth machine brought together developers and local and national politicians, together with a banking sector that became over-committed to residential and commercial real estate. This enabled short-term returns to the property investors but undermined coherent spatial planning, resulting in highly negative spatial planning outcomes at the urban, city-regional and national scales. For example, ‘ghost estates’ of unsold or unfinished housing in many counties were symptomatic of the failures of planning due to the over-zoning of residential land in some areas. Simultaneously, in Dublin, a crisis of housing affordability, constrained supply and the unplanned outward sprawl of the city, occurred.

Post-crisis, Dublin faces a series of planning challenges, including a deepening crisis of housing affordability and strategic infrastructure deficits, compounded by three key factors. First, the architecture of the state, revealed in a preference for national agencies or central government to address ‘local’ problems, typically in uncoordinated ways. Second, weak and competitive local government which results in competition between local authorities for major projects, in pursuit of fiscal revenue through property rates and development levies. This produces suboptimal outcomes such as occurred in Dublin, exemplified by the building of three regional-scale shopping centres in different local authority areas but within 25 km of each other on the orbital M50 motorway. The model of governance in the Dublin city region rewards competition rather than co-operation between local authorities.

Third, these conditions favour politicised private actors who can play the zoning game. Public investigations and tribunals have highlighted the sometimes corrupt relationships between private developers and some local politicians. Prior to the financial crisis of 2008, weak local and heavily siloed central government was functional for private developers even if it produced regressive social outcomes and spatial planning failures. Direct access by the developers to local and national politicians made possible extensive rezoning, irrespective of infrastructure provision. The growth coalition showed little inclination to think systematically about metropolitan governance and planning.

In a tacit admission of the previous failures of Irish land-use planning, in 2018 the Irish government published a National Planning Framework. Although this calls for the preparation of Metropolitan Area Spatial Plans (MASP’s), it largely backs away from proposing governance frameworks that would support a strategic approach. The MASPs are being relied on to deliver change without real political authority. Unusually, in a European context, national politics have not favoured Dublin. While there has been significant central government activity in Dublin, there is comparatively little government of Dublin as a metropolitan entity. A general reluctance to engage with the metropolitan as a distinct territorial scale across institutions and scales of government demonstrates a deeply rooted ‘metrophobia’ at work in the Irish context.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Giuseppe Milo (CC BY 2.0)

_________________________________

John Tomaney – University College London

John Tomaney – University College London

John Tomaney is Professor of Urban and Regional Planning in the Bartlett School of Planning at University College London.

–

Niamh Moore-Cherry – University College Dublin

Niamh Moore-Cherry – University College Dublin

Niamh Moore-Cherry is an Associate Professor of Urban Governance and Development in the School of Geography, University College Dublin.