Freedom of movement was one of the major issues during the UK’s EU referendum, but how do citizens in other EU countries view the topic? Drawing on new research, Sofia Vasilopoulou and Liisa Talving explain that although freedom of movement is popular overall among EU citizens, there is substantial variation between countries, with citizens in richer member states likely to have more negative views.

Freedom of movement was one of the major issues during the UK’s EU referendum, but how do citizens in other EU countries view the topic? Drawing on new research, Sofia Vasilopoulou and Liisa Talving explain that although freedom of movement is popular overall among EU citizens, there is substantial variation between countries, with citizens in richer member states likely to have more negative views.

As a key principle of European integration, mobility is not only important symbolically but also entails important challenges. There is a tension between the EU’s objective to increase competitiveness and address unemployment on the one hand, and member states’ ability to regulate their domestic labour market institutions on the other.

We know, for example, that concerns over intra-EU migration were central to the Brexit referendum vote and have been omnipresent during the Brexit negotiations. But to what extent is scepticism about the EU’s freedom of movement principle UK-specific? In a recent study, we find that despite overall high levels of support for EU freedom of movement, there is a great degree of cross-country variation.

What Europeans think about freedom of movement

To examine European citizens’ attitudes towards freedom of movement, we rely on individual-level data from four Eurobarometer survey waves conducted between 2015 and 2017 which ask:

What is your opinion on each of the following statements? Please tell me for each statement, whether you are for it or against it. “The free movement of EU citizens who can live, work, study and do business anywhere in the EU”.

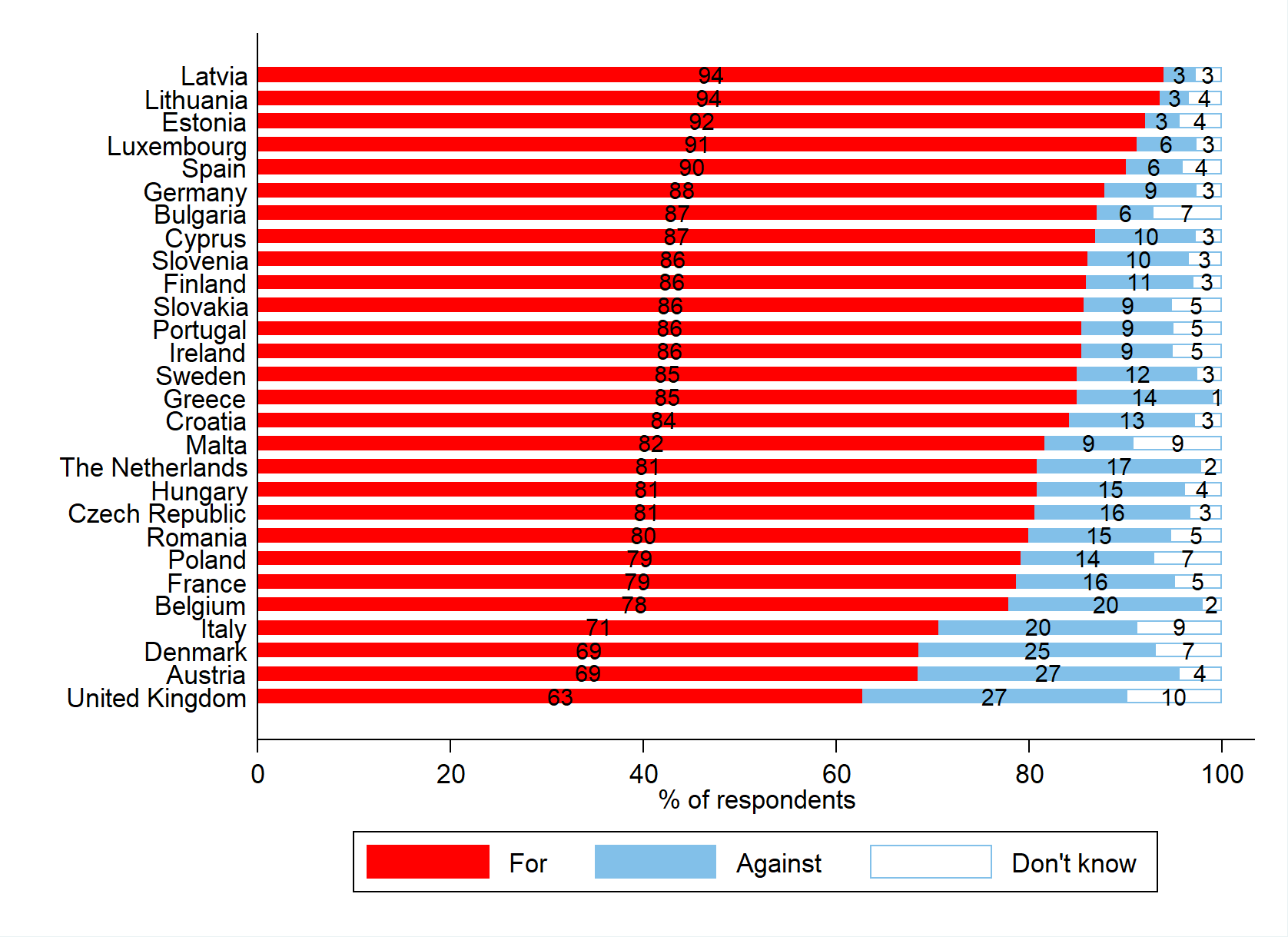

On average, 82.4 per cent of respondents support and 13.1 per cent oppose free movement of citizens, with only 4.5 per cent not expressing a clear view. Overall support levels have largely remained the same from one survey to another, ranging between 80 and 83 per cent.

There is, however, a great degree of variation across countries. Stronger opposition to free movement of EU citizens may be found in Western Europe. Countries with the highest opposition score include the UK with 27.3 per cent of respondents being against the policy, followed by Austria at 27 per cent and Denmark at 24.6 per cent respectively (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Support for EU freedom of movement by country

Source: Eurobarometer 84.3 (November 2015), 85.2 (May 2016), 86.2 (November 2016) and 87.3 (May 2017)

These results contrast with Southern European countries such as Greece, Portugal and Spain, where the proportion of negative views is 14 per cent, 9.4 per cent and 5.8 per cent respectively. Attitudes also vary significantly among Central and Eastern European countries. Interestingly, we may observe relative opposition to EU freedom of movement in Hungary (15.2 per cent), Romania (14.7 per cent) and Poland (13.8 per cent). The Baltic states, on the other hand, show the lowest levels of negative attitudes towards the EU’s freedom of movement with only 2.8 per cent in Lithuania, 3.2 per cent in Latvia and 3.4 per cent in Estonia.

What explains variation in European citizens’ attitudes towards EU freedom of movement?

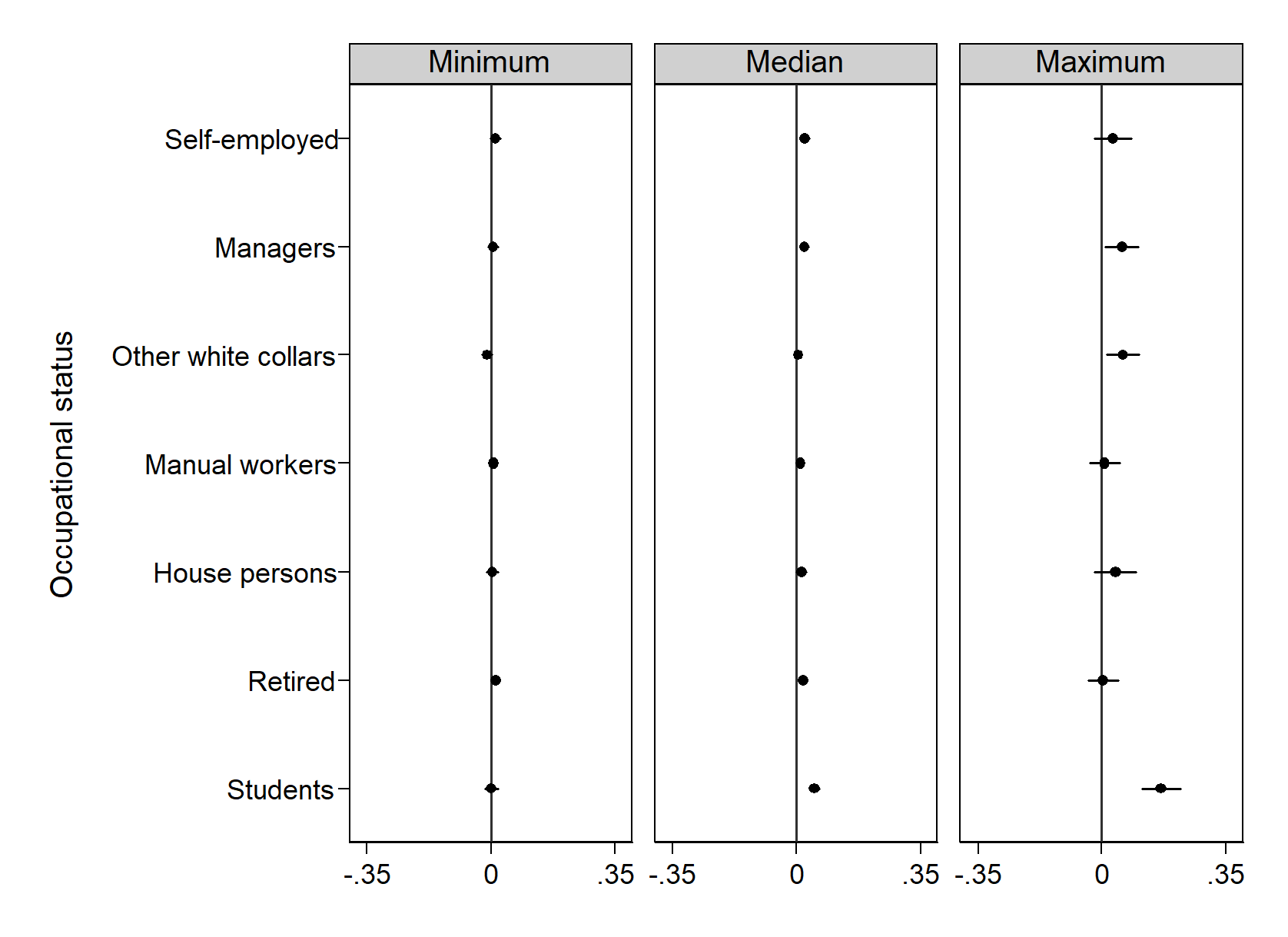

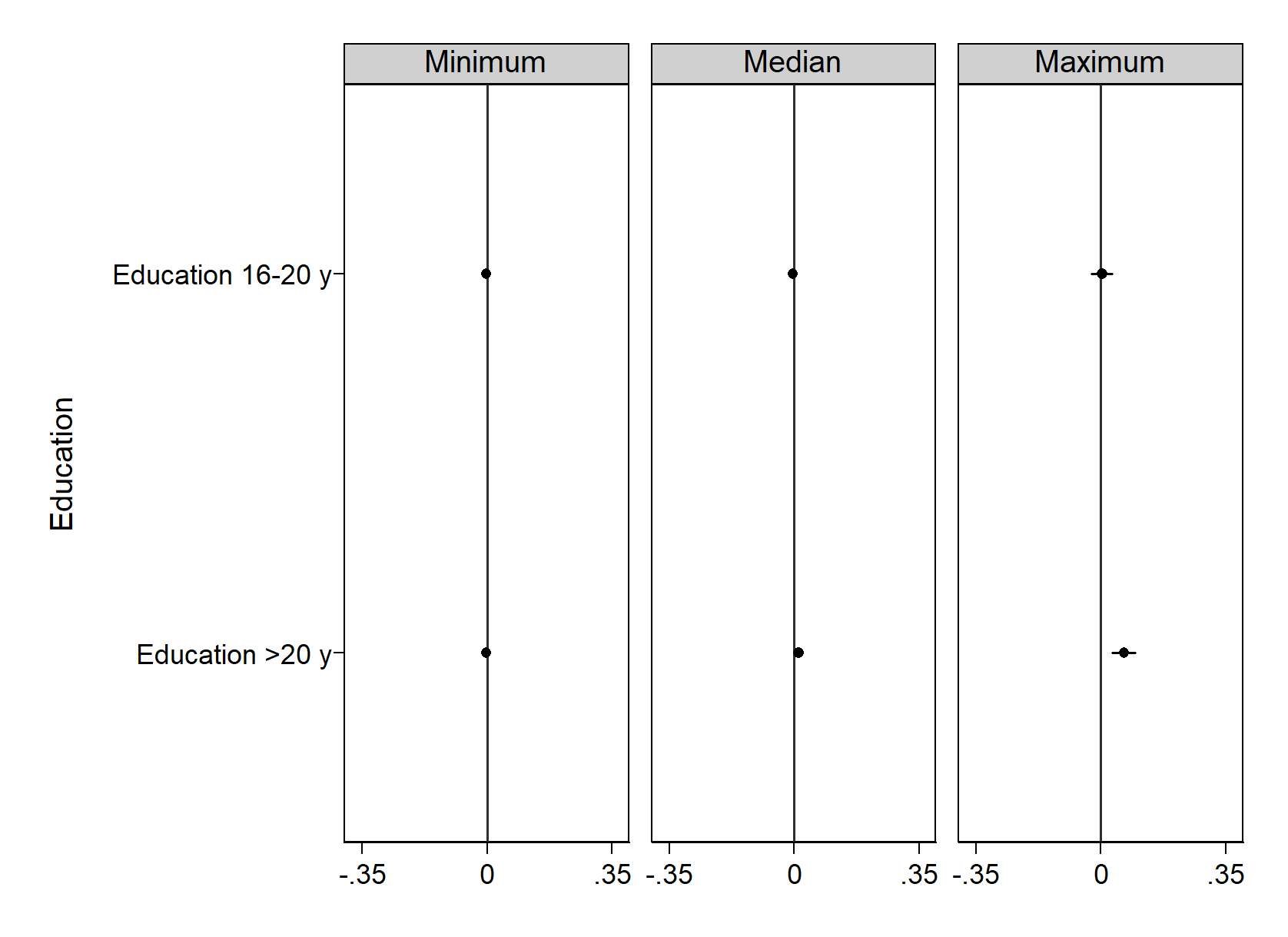

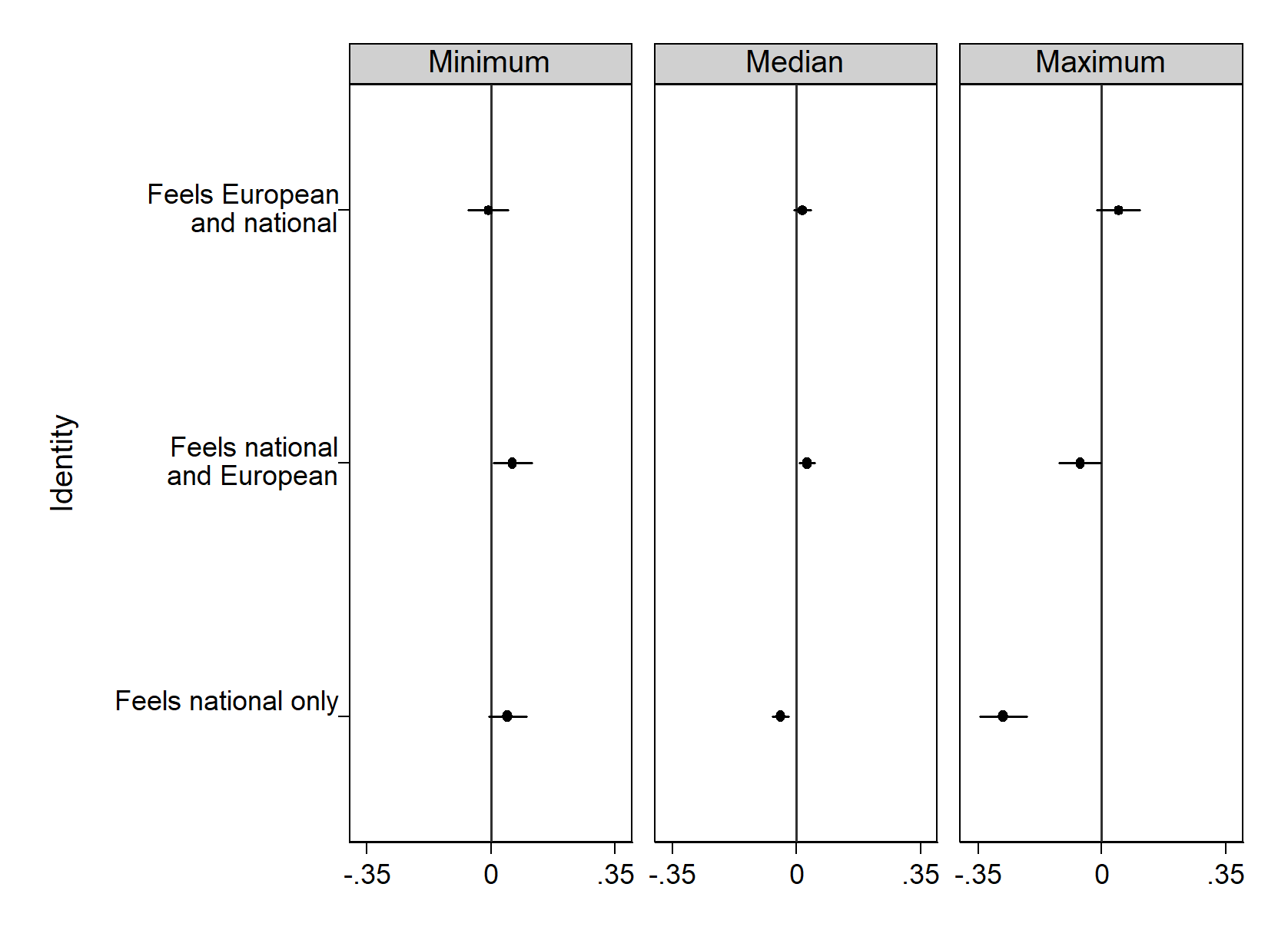

We know that socio-economic indicators, such as occupational skills and education, as well as group identities matter in terms of how people view the EU and its policies. Our data show that these factors are also crucial in explaining individual-level variation in support for freedom of movement.

Compared to unemployed citizens, other occupational groups, including the self-employed, managers, manual workers, house persons, the retired and students, have a higher probability of endorsing freedom of movement. Higher-educated individuals are also more likely to support intra-EU mobility compared to those with low levels of education. In addition, citizens with strong feelings of national identity are significantly less supportive of intra-EU mobility.

The role of a country’s economic context

However, although statistically significant, such differences are not large in substantive terms. Our data show that the key predictor of Europeans’ attitudes towards freedom of movement is country-level economic affluence measured as national GDP in euros per capita for a quarter previous to survey fieldwork.

Support levels for EU freedom of movement are higher in poorer countries, but lower in richer EU member states. These differences are large in substantive terms. For example, the likelihood of approval of free movement is 96 per cent for the country with the lowest GDP per capita in the sample (Bulgaria in May 2017), 88 per cent for the median country (Spain in November 2015), and only 71 per cent for the wealthiest one (Luxembourg in May 2017).

This suggests that citizens in richer countries that tend to receive more EU migrants and where the question of EU mobility is more salient seem to be more prone to perceiving EU freedom of movement as a threat. We argue that the context of macro-economic performance as a pull-factor of intra-EU migration may direct individuals in more affluent member states to pay more attention to the potential consequences of EU freedom of movement. In rich member states, increased intra-EU mobility may stimulate discussions regarding its potential effects on domestic employment and access to labour markets. It may also raise concerns over redistributive politics, the provision of public services, access to welfare, and competition for the collective goods of the state with EU citizens who are nonetheless non-nationals – despite the fact that these concerns may not necessarily be supported by objective evidence.

Country economic context also moderates the link between individual-level considerations and support for freedom of movement. Figure 2 clearly demonstrates that in poor countries, support for free movement is evenly high among different population groups, including those with low socioeconomic status and weak European identity. On the other hand, attitudes in richer member states depend on individuals’ economic and identity considerations: support for free movement varies across different population groups, being highest among students, high-educated citizens and those with a strong European identity.

Figure 2: Individual-level effects on support for EU freedom of movement by GDP categories

Note: Average marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals. Reference categories: unemployed; education<15 y; feels European only. Source: Eurobarometer 84.3 (November 2015), 85.2 (May 2016), 86.2 (November 2016) and 87.3 (May 2017).

What are the implications of our findings?

Despite the fact EU freedom of movement primarily relates to policy-making and implementation – in particular access to European labour markets, employment and welfare – it can stir up conflict over constitutive issues of the EU polity, including EU membership, EU competencies, and the extent to which labour mobility should be one of the cornerstones of European integration.

It may also place a strain on European solidarity. This was particularly visible during the Brexit referendum. Although another EU membership referendum is not currently on the cards, our findings have significant implications with regard to the politicisation of EU freedom of movement in richer Western EU member states. Far right EU issue entrepreneurs in these countries have a ready reservoir of negative opinion towards freedom of movement to draw upon during electoral campaigns.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Sofia Vasilopoulou – University of York

Sofia Vasilopoulou – University of York

Sofia Vasilopoulou is Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of York. Her work examines political dissatisfaction with democracy and democratic institutions across Europe. Specific themes include Euroscepticism, extremism, and loss of faith in traditional politics. She leads an Economic and Social Research Council Future Leaders Project entitled “Euroscepticism: Dimensions, Causes and Consequences in Times of Crisis.”

Liisa Talving – University of York

Liisa Talving – University of York

Liisa Talving is an Associate Lecturer of Politics at the University of York. Her research interests include determinants of citizens’ political behaviour and political attitudes, cross-country comparative research, and quantitative research methods. Her work focuses on EU attitudes and economic voting. She is currently involved in the Economic and Social Research Council Future Leaders Project “Euroscepticism: Dimensions, Causes and Consequences in Times of Crisis.”

Few people have a problem with freedom of movement provided some controls are in place. Perhaps if you had asked how many people are worried that freedom of movement is being exploited by economic migrants from outside the EU you may have come out with a whole new set of results. Also the freedom of movement that allows anyone, including criminals, to come into member states is a hugely dangerous thing. Research is only as good as the questions asked and the numbers who participate in it.

How can someone who is not an EU / EEA national exploit “freedom of movement” round the EEA for EEA nationals?

What a load of nonsense. During the EU referendum in the UK, the vast majority of remainers agreed freedom of movement was a negative and so did the politicians as no one argued the benefits for it during the campaign. So if you consider that as well as nearly all leavers being against freedom of movement then you have a figure in the UK of closer to 75+ percent against. The sample has been clearly very carefully chosen and can not be considered trustworthy due to the clear false claim of the UK’s attitude to freedom of movement. This also brings into question the evidence and sample from other EU nations in the study. Similar issues arise in polls conducted by Yougov. What sort of people sign up to Yougov to take part in polls? These polls attract the same sort of people. Most leavers can’t be bothered to talk about the EU or brexit. Leavers just get on with life until the next vote comes along and the “polls” are upset again.

Freedom of movement is one of the founding bases for an effective European Union. It is more efficient for business, it does incentivate a shared cultural base and reinforce the shared committment and responsability to manage a common EU border. We all need to support a true EU Freedom of Movement.

Freedom of Movement is OK if doesn’t become too unbalanced.

In most European schools English is taught as a second language. Therefore EU citizens have a predisposition to come to the UK rather than anywhere else. This is a culture driven choice not an economic choice but it has economic effects. Net immigration will remain positive for the indefinite future under EU membership until it puts such a strain on our infrastructure and society that people will no longer want to come here. At that point we will remain indefinitely at rock bottom.

The EU is indifferent to this issue, because it is specific to only one member country.

What you’re describing here isn’t a problem, it’s a competitive advantage. There’s an inbuilt pull factor in the UK that allows it to attract the best workers across Europe, pushing up standards, generating growth and improving the economy.

Instead of seeing that as an advantage, the UK is now trying to erect barriers to prevent these workers coming to the country. Politicians will say they can “still allow skilled workers in” but that’s completely missing the point that the more barriers you put in place, the less attractive a destination the UK will become. The UK is attractive for certain reasons, such as the one you’ve mentioned here in relation to English, but it’s not so attractive that it can afford to put obstacles in the way of workers who have other options – English is not only spoken in the UK, it’s used in many business contexts across Europe (not to mention Dublin/Ireland).

Also the best staff are the ones who have the most options, so these barriers will have a disproportionate effect on the highest quality workers. The UK gains a great deal from EU migrants, but they aren’t going to stick around when they get treated like second class citizens, get vilified by politicians/the media, get treated like a drain on the economy, and have to go through a bureaucratic/expensive rigmarole just to have the “privilege” of getting to work there. Why should they if they can work somewhere else like Germany and have more rights and potentially better wages?

And this is all because many people in the UK are convinced immigration is a net negative under most circumstances. They think that public services naturally become strained when the population increases (which isn’t true), that EU immigration causes unemployment (no evidence for this), that it drives down wages (very limited evidence of this and only for the lowest skilled workers who could be protected via domestic policy such as a better minimum wage), and so on. Most of these are basically simple misunderstandings that politicians have an obligation to address when they speak to the public, but almost no British politician will do this as they don’t think it’s a vote winner to seem pro-immigration.

Well, it’s the UK’s loss. The rest of us in Europe are happy to benefit from your demise if you insist.

https://www.vg.no/nyheter/innenriks/i/Qm1bEx/nav-granskeren-kritiserer-stortinget-skaper-usikkerhet is in Norwegian but can be read via Google translate

Norway is in the midst of a still-growing, biggest post-war legal scandal dubbed “NAV Skandalen”

The EU and EFTA Surveillance Authority, Council of Europe, EU commission and EFTA have turned a blind eye to Norway’s failure, since 1994, to correctly apply the EEA Agreement

Effectively, Norway has been aggressively defining as resident in Norway “for tax purposes” EU nationals and forcing them to contribute to Norway’s National Insurance Scheme from which they can get no benefits on the grounds the EU nationals are not resident in Norway as their applications for residence permits failed due to them not being in Norway enough

It seems that so long as you keep sending money to Brussels, they’re not too bothered what happens to EU nationals encouraged to move and work around the EEA

The EU has made no comment on NAV Skandal in the 18 months since it was announced. Norway’s parliament just voted through laws contrary to the EEA Agreement insisting individuals must remain in Norway whilst receiving benefits. Norway lost the “Stig Arne Jonsson” case in 2013 and ignored the EFTA Courts verdict in that case, on May 5th 2021 the EFTA Court pretty much confirmed the 2013 ruling … rights that cannot be enforced are not rights at all