As support for right wing movements and political parties has grown, so has the idea that cities might act as progressive bastions in an increasingly populist and illiberal national landscape. But as recent election results across Europe demonstrate, cities are not immune to the divisive discourses and increasing polarisation surrounding the green transition, write Catarina Heeckt and Francesco Ripa.

Four years ago, commentators across Europe were trying to make sense of the Greens’ unexpected success in the 2019 European elections and heralding a new era of green-left leadership and influence across the continent. A pandemic, a war and an energy and cost-of-living crisis later, the political landscape has shifted. The green wave has turned blue, with some patches of black.

Over the past year, right-wing parties have made significant gains across Europe. Right-wing nationalists are now governing outright in Italy and Hungary, have recently joined the governing coalition in Finland and support the government in Sweden. And although Poland’s pro-EU opposition parties defied expectations and won enough seats to oust the nationalist Law and Justice party (PiS) in the country’s recent elections, PiS still took the largest number of votes.

Across the continent, far-right populist parties are moving steadily closer to the mainstream, entering parliament in greater numbers, acting as kingmakers and propping up centre-right coalitions. Former fringe parties on the right now rank among the top three most popular political groups in almost half of EU countries, including France, Spain, Germany and Belgium. This renewed influence is shaping political alliances in Brussels too, with commentators increasingly expecting that right-wing parties will see sizeable gains in the European Parliament elections in June 2024.

Are cities shifting to the right alongside their nation states?

But what is happening at the city level? After all, Europe’s cities have historically leaned to the left of their nation states and much has been made of the growing political divergence between progressive cities and their more conservative hinterlands.

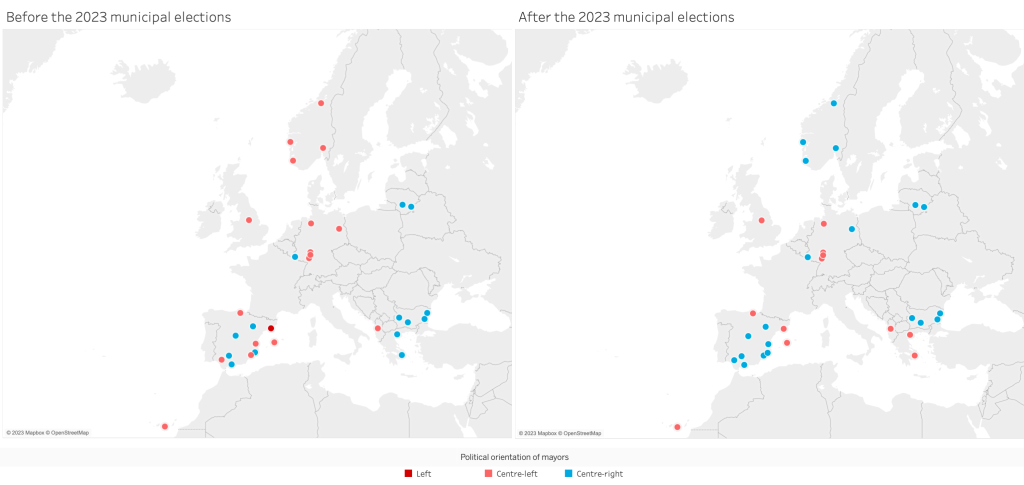

We have taken a closer look at the data from the 162 cities in our European Cities Knowledge Hub. Since the beginning of 2023, local elections have taken place in 34 of the cities. In 19 of those cities, either the mayor was re-elected or party affiliation didn’t change. Of the remaining cities, eleven saw a shift from centre-left to centre-right (Berlin, Mannheim, Murcia, Palma, Sevilla, Valencia, Zaragoza, Oslo, Bergen, Sandnes and Trondheim) while Barcelona shifted from left to centre-left, Darmstadt shifted from green to centre-left and Vilnius from liberal to centre-right. Only the recent Greek and Bulgarian local elections seem to have gone against this rightward tide, with incumbent centre-right mayors losing to centre-left and centrist challengers in Athens, Thessaloniki, Sofia and Varna.

Figure 1: Political orientation of mayors before and after municipal elections in 2023

Note: For the purposes of this blog, green and liberal city leaders have been categorised as centre-left.

Our European Cities Knowledge Hub only collects information on large cities (over 100,000), so this data doesn’t capture the shift happening in smaller municipalities. Take Spain, where voters cast ballots to elect mayors in more than 8,000 municipalities back in May 2023: 40% are now governed by the centre-right, in 200 cases in coalition with the far-right VOX party, including in provincial capitals such as Valencia, Burgos, Valladolid and Toledo. And while the far-right to date has less sway in Europe’s largest cities, they are a rising force in smaller towns, as the narrow defeat of the Alternative for Germany’s mayoral candidate in Nordhausen showed last month.

What is driving the rejection of progressive politics in cities?

The reasons for this shift are complex and context dependent. However, a few recurring themes seem to have motivated voters at the polls. Alongside the expected focus on immigration, safety and economic stability, a rejection of ambitious climate and sustainable mobility policies were also common denominators.

Green policies have developed into a central battleground in many of the cities in our sample, with right-wing politicians seizing on interventions that reallocate road space and curb car dependency. The local elections in Norway, where conservatives took over from the social democrats for the first time in nearly 100 years, are only the latest example. This historic defeat was fuelled by opposition to highly ambitious policies which sought to ban cars and remove parking spaces from inner cities and to advance a progressive nation-wide climate agenda.

The evidence is unequivocal: Europe will not meet its climate targets without a fundamental transformation of the way we live and move in cities. While such rapid and all-encompassing changes have high short-term costs, they also bring the significant and immediate benefits of living in safer, greener and more inclusive cities. And yet, a growing number of voters seem to view green initiatives as too expensive and too inconvenient, creating a rift that more conservative parties have been able to exploit for electoral advantage.

While it is too soon to say how the newly elected mayors will govern, some of their early words and actions are instructive. In Darmstadt, the new mayor vowed to “de-escalate the contentious mobility conversation in the city” that he claimed had been started by his Green predecessor. In Mannheim, a traffic free zone in the inner-city has reopened to cars. Berlin’s new centre-right mayor justified halting road closures and cycling lane expansion by asserting that “Berlin is a world metropolis, not a quaint village”.

In Seville, the new mayor confirmed the scrapping of a traffic calming plan for the inner city. One of the early actions of the new mayor of Murcia was to reopen a bridge to car-traffic, while Palma’s new mayor decried his predecessor’s “ideological stance” on transport policy and vowed to tackle high-occupancy vehicle lanes and a lack of parking spaces. In Barcelona, the new administration has wasted no time rolling back some of the ambitious mobility and public space interventions championed by the outgoing mayor Ada Colau.

Across Europe, we are seeing real momentum behind this “greenlash” – and cities have not bucked the trend. Far from being a policy agenda that can bridge ideological divides and unite Europeans behind a common cause, ambitious climate action has become the new frontline of the culture wars.

What’s more, growing concerns over the costs of the green transition are hitting a nerve with voters amid the ongoing cost of living crisis. Even though polls show that a large majority of European citizens are worried about climate change, voters are prioritising pocketbook issues over climate issues, providing further evidence that at the ballot box concerns about the “end of the month” prevail over those about the “end of the world”.

One of the most high-profile mayoral races coming up in 2024 will act as a litmus test for the power of green policies to win local elections in the current political climate. London’s mayor Sadiq Khan is running for a historic third term, staking his legacy on the fight for cleaner air, even as the central government continues to dismantle the net zero agenda and delegitimise efforts to fight the climate crisis.

Recent election defeats of candidates running on ambitious, green-left platforms across Europe should provide some useful lessons for Mr Khan. He needs to understand the importance of listening very carefully to the concerns and fears of voters, of engaging continuously with communities to build trust and communicate the wider benefits, and of proactively mitigating the costs for the most vulnerable. If urban leaders are not able to do these things effectively, the ambitious climate and environmental policies our cities need and deserve will continue to be framed as “luxury beliefs” when nothing could be further from the truth.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Mistervlad/Shutterstock.com

Hi Catarina and Francesco, very insightful and though-provoking piece; many thanks. Constituents moving to the right is now clearly aligning with unfit-for purpose institutions (and underlying discourses) we inherited from the Market-Led Global Era (e.g. German Debt break). Green and Progressive therefore struggle to deliver on ambitious transformation tasks. Need honest debates on how to revitalise and broaden the Progressive Movement in times of fear and prosperity decline!