Sweden’s European Parliament election will be held on 26 May. Linda Berg and Jonathan Polk explain that as the elections will come less than a year after the country’s last general election, there may be an expectation they will be more ‘second order’ than usual. Yet, a trend towards higher turnout for EP elections in Sweden, increasingly favourable public opinion on Swedish membership in the EU, and high levels of early voting indicate that a genuinely European dimension may be relevant to this year’s elections as well.

Sweden’s European Parliament election will be held on 26 May. Linda Berg and Jonathan Polk explain that as the elections will come less than a year after the country’s last general election, there may be an expectation they will be more ‘second order’ than usual. Yet, a trend towards higher turnout for EP elections in Sweden, increasingly favourable public opinion on Swedish membership in the EU, and high levels of early voting indicate that a genuinely European dimension may be relevant to this year’s elections as well.

The 2019 European Parliament (EP) election in Sweden will take place at a much different time in the domestic electoral calendar than the EP election of 2014. In 2014, the EP election was just slightly more than three months before the parliamentary, regional and local elections of September 2014, which added an incentive for political parties and voters to engage in the EP campaign. This contrasts sharply with 2019, where the EP election will be held half a year after domestic elections, several years prior to the next scheduled elections and after an unusually prolonged and conflictual government formation process.

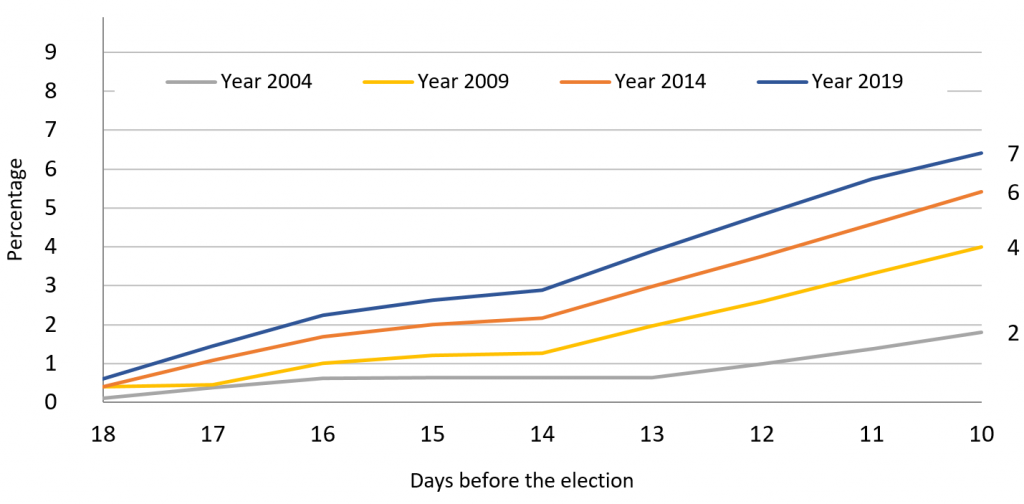

The combination of these latter factors would normally suggest depressed voter turnout for 2019. Fatigue with the extensive coalition negotiations, and the substantial time gap before the next major national elections, work against a large number of citizens turning out to vote. Yet, Sweden has also broken the ongoing trend of declining turnout at EP elections, and was above the EU-wide turnout average for the last two EP contests. If this trend continues, we may see turnout figures well over 50 per cent. So far, citizens’ self-reported turnout intention has been polling higher than in 2014. Moreover, advance voting in Sweden opened on 8 May, and the flow of incoming votes indicates a potential slight increase in turnout, compared to similar time periods before the earlier European Parliament elections.

Figure 1: Early voting per day before the Swedish European Parliament Elections 2004-2019 (cumulative percentage of votes per day)

Note: The figure shows the percentage of the electorate that have cast their vote in the European Parliament election 2019, per day before the election (early voting). For daily updates until the election, see Richard Svensson’s blog. Source: Swedish Election Authority and the Swedish National Election Studies Program.

The domestic political backdrop for the 2019 EP election is one of party system change. Although there are eight political parties in the national parliament, contemporary Swedish politics has been dominated by a rather cohesive left bloc, led by the Social Democrats, and a right bloc, led by the Moderates. The stability of this bloc politics has eroded in recent years due, in part, to the rise of the anti-immigrant, Eurosceptic Sweden Democrats. With the other parliamentary parties unwilling to formally cooperate with the Sweden Democrats because of their anti-immigration stance, it has become increasingly difficult to achieve working coalitions within the Riksdag. This situation reached an apex after the 2018 national elections, in which the Sweden Democrats received its largest vote totals ever, producing party system fragmentation in line with what we have seen across Western European democracies.

The corresponding tension was most intense for the four party centre-right bloc, The Alliance, which ultimately split up in the context of the 2018-2019 government formation negotiations. The socio-culturally liberal Centre and Liberal parties agreed to passively accept the Social Democrat-led minority government, while the more socially conservative Moderates and Christian Democrats appear increasingly open to working with the Sweden Democrats in the future.

It remains to be seen what impact, if any, this upheaval in the Swedish party system will have in the 2019 European Parliament election. In the European Parliament, however, there has never been an Alliance, as the two liberal parties belong to ALDE and the Moderates and Christian Democrats belong to the EPP group. Concerning the latter party group, both the Moderates and the Christian Democrats have spoken out against the continued membership of Fidesz, the party of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, reflecting an increasing concern among Swedish voters about the erosion of liberal democracy within other EU member states.

Polling indicates diverging trajectories for two former Alliance members. In addition to leaving the centre-right coalition, the Liberals, the most staunchly pro-EU party in Sweden, recently changed party leader as well. They are currently projected to do substantially worse than their 2014 EP result of 10 per cent, and might even lose representation. The Christian Democrats, however, have seen favourable poll numbers indicating that they could receive as much as 11 per cent of the vote, a substantial increase from both their 2014 EP and 2018 national result.

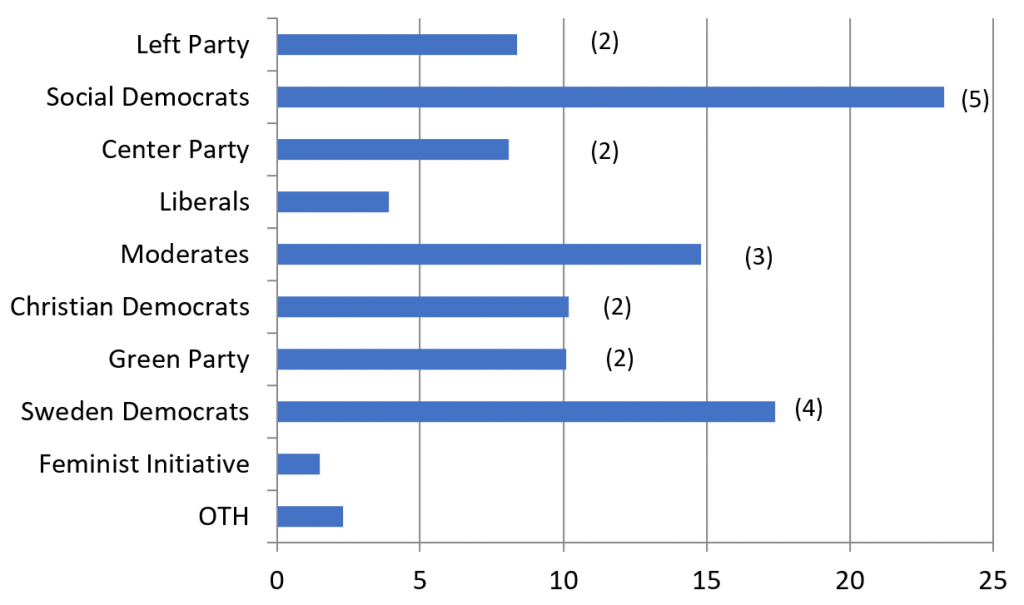

The Social Democrats, the major party of the left, continue to be first in the polls with an average expectation of around 23% of the vote. The Green Party, at roughly 10 per cent, is on track to do worse in 2019 than their 2014 election result, but this would still be over twice as many votes as they received in the national election in the autumn of 2018. The Greens’ consistently stronger performance in EP elections compared to those for the Riksdag indicates the high priority Swedish voters place on questions of climate change and the environment at the European level. The Moderates have decreased in the polls over time, and are not far from their record low result of 13.7 per cent, in the 2014 elections, and clearly below the Sweden Democrats polling an average of 17%.

Figure 2: Poll of polls voting intention in the 2019 European Parliament elections in Sweden (per cent, number of seats)

Note: The numbers in the figure are based on the five latest (as of 16 May 2019) opinion polls in Sweden, asking “Which party do you intend to vote for in the European Parliament election 26 May 2019?”. The sample sizes range from 1595 (Demoskop) – 2867 (Kantar Sifo). The expected number of seats per party (in parentheses) is based on a total number of 20 seats in the European Parliament (after Brexit Sweden will have 21 seats, to be added to the Social Democrats according to this poll of polls).

The Sweden Democrats (SD) are polling strongly in 2019 and are the most EU-critical of the political parties in the country, but it is important to emphasise that SD has softened, or at least modified, its criticism of the EU considerably over the last year. Following a trend in Eurosceptic parties across the continent, SD no longer advocates for Sweden’s departure from the EU but rather pushes for reform from within the European Union. What is more, unlike similar parties in the region such as the Danish People’s Party or True Finns, SD currently does not plan to join Matteo Salvini’s proposed anti-EU political group. At the same time, the Left Party, the other most EU critical voice of the Swedish parties has also softened its position on EU membership. In general, this reflects the fact that rather than leading to an increased desire to leave the EU, public opinion has actually become more favourable about continued Swedish membership in the European Union since the 2016 Brexit referendum. As of Monday, 20 May, SD struck one of its EP candidates, Kristina Winberg, from its list allegedly because she indicated that SD’s top candidate, Peter Lundgren, had sexually harassed a woman at a party. It remains to be seen if this will have electoral ramifications for SD.

Turning to the other challenger parties in the Swedish system, the Feminist Initiative, currently below two per cent in the polls, looks likely to come in under the 4 per cent electoral threshold. If the Feminist Initiative loses its seat after a single parliamentary period it would follow the example of previous challenger parties, i.e. the June List and the Pirate Party, that both failed to renew their representation after one term. This year, no new challenger party has made a mark in the polls.

So while the timing of the electoral calendar and domestic politics lead to an expectation of depressed turnout and voting based on a national agenda, the trend towards higher turnout for EP elections in Sweden, increasingly favourable public opinion on Swedish membership in the EU, and high levels of early voting in 2019 indicate that a genuinely European dimension will be relevant for 2019 as well.

This is in line with our own research on the topic, which shows that Swedes tended not to vote in a way consistent with the expectations of the second order national election model in 2014, and that citizens were more likely to vote for a different party in the 2014 EP election than they did in the previous national election if they saw themselves as incongruent with that party on the EU and prioritised the European dimension.

More information on Sweden and European Parliament elections is available in both English and Swedish through a series of fact sheets produced in cooperation between the Centre for European Research and the Swedish National Election Studies program.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Daniel Kulinski (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

_________________________________

Linda Berg – University of Gothenburg

Linda Berg – University of Gothenburg

Linda Berg is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Gothenburg. She is also Director of the Centre for European Research, University of Gothenburg (CERGU).

–

Jonathan Polk – University of Gothenburg

Jonathan Polk – University of Gothenburg

Jonathan Polk is Associate Professor in Political Science at the University of Gothenburg. He is also an affiliated researcher at the Centre for European Research, University of Gothenburg (CERGU).