The composition of the European Parliament is often discussed with reference to the balance of power between parties on the left and right of the political spectrum. But given the rise of new parties that define their ideology based on their support for or opposition to European integration, is this left-right divide still relevant? Drawing on a new study, Nicolò Fraccaroli and Anatole Cheysson illustrate that the rise of Euroscepticism has mainly impacted on the budget rather than ordinary legislation, but it remains unclear whether as Eurosceptic parties increase their presence, we may see a re-emergence of left-right politics.

Are the left and right still relevant categories for understanding European politics? As far back as the 1980s, in his seminal book Neither Right Nor Left, Zeev Sternhell cast doubts on their importance. In his study on the origins of the French Fascist party, he noted how the party combined ideological elements belonging to both poles, making the distinction between the two more blurred – something that applied also to the more successful Italian Fascist party. A decade later, however, Norberto Bobbio reopened the debate. In an equally influential book, Right and Left, the Italian political scientist argued that the merge of left and right – in those years reproposed as a ‘Third Way’ – was not a symptom of their extinction, but rather of their persistent importance. As he put it, “the ideological tree is always green” (p.3).

This unsettled debate has re-emerged in view of the upcoming European elections. New parties such as Macron’s En Marche, the Italian Movimento 5 Stelle (Five Star Movement), the Brexit Party and the Spanish Vox all seem to define their ideology and European transnational alliances based on their support (or opposition) to European integration, rather than on their left-wing or right-wing identity. Is this because the traditional distinction between left and right is dead? And if this is the case, what can we expect from the next European Parliament?

In a recent study, we tried to answer these questions by looking at the voting choices of Members of the European Parliament on 22,980 votes, representing all the plenary votes cast from 2004 to 2019. Using a statistical method called Principal Component Analysis, we were able to extract from this huge amount of information (the combination of votes and parliamentarians results in a matrix with more than 20 million cells) two common and orthogonal (meaning independent from one another) patterns, or components, that explain the dimensions on which politicians decided to coalesce when voting. In other words, our results show that for more than 50% of the times Members of the European Parliament had to vote, they decided to take a stance based on either one pattern or the other (for more details on how our methodology works, see the paper).

Ideology in the current European Parliament (2014-2019)

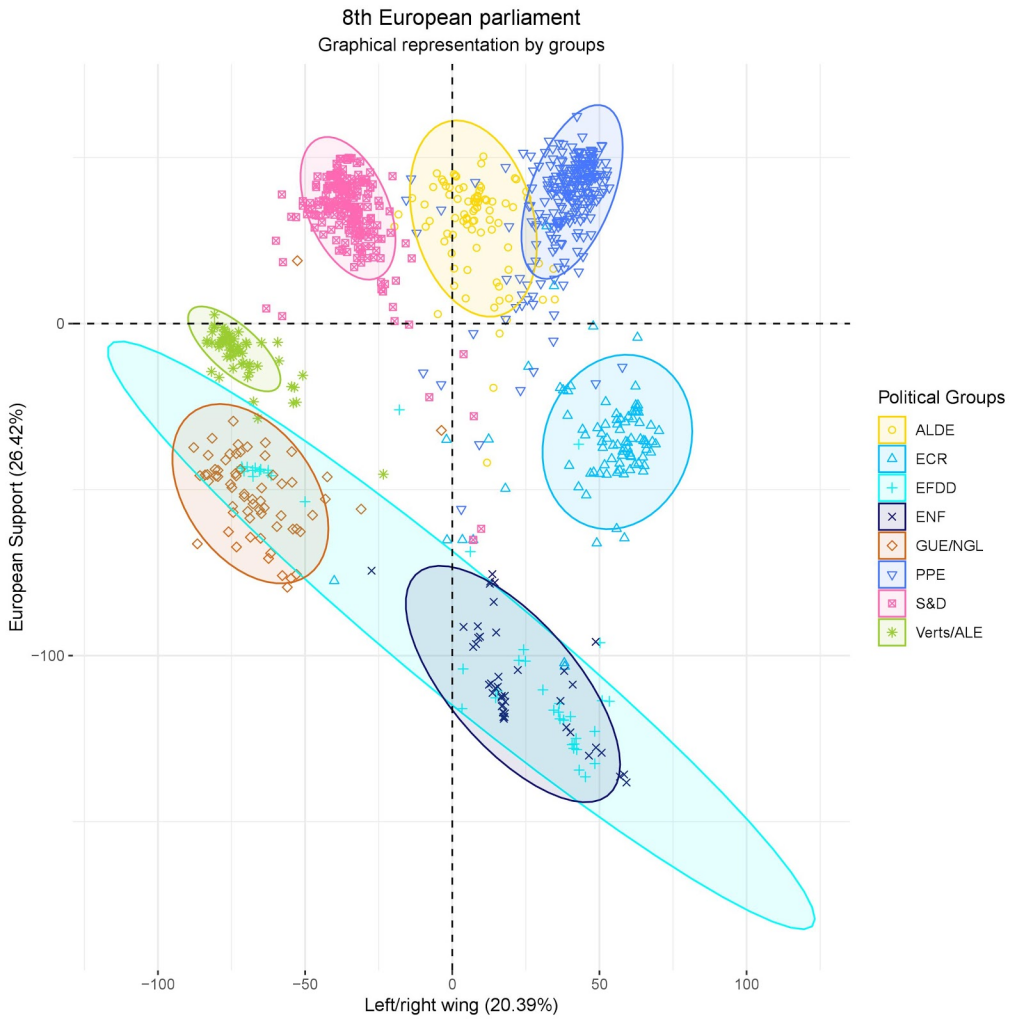

We found that these two principal components correspond to the degree of support for European integration and to the traditional left-right axis. The results for the current parliament (2014-2019) are displayed in Figure 1, where each dot represents a Member of the European Parliament. On the left side of the chart we identify parties that we generally associate with the idea of left. The GUE/NGL group (brown dots) is the group of the united left and includes, among others, the Greek Syriza, Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise and the Portuguese Bloco de Esquerda.

While their position is close to the one of green parties (Verts/ALE, green dots), they are placed further on the left with respect to centre-left parties, i.e. the social democrats of the S&D (red dots), which are located in a more centrist position. This group includes the German SPD, the Italian Partito Democratico, and the British Labour Party. The centrist liberal democrats of ALDE (in yellow) are instead located exactly in the middle, indicating that they vote occasionally with the left or the right, or abstain when the two blocks diverge.

On the right-axis we find the centre-right EPP (blue), the largest group of the parliament, which gathers together the CDU/CSU, the French Republicains, Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and Orban’s Fidesz. While their position is close to the conservatives of the ECR (light-blue), the far-right parties belonging to ENF (blue navy) and EFDD (cyan), they are far from these groups on the vertical dimension. This dimension represents the support for European integration and, as we see, proposes a different way of forming coalitions in the parliament: moderate parties from the centre-left to the centre-right are located in the upper part of the chart, meaning that they tended to support together legislative files in favour of further integration. In contrast, in most of these occasions they found the opposition of parties located at the bottom of the chart (Eurosceptic and nationalist parties), whereas parties in the middle (greens, left and conservatives) alternatively supported one cluster or the other.

Figure 1: Result of the principal component analysis on the 8th European Parliament (2014-2019)

Source: Cheysson and Fraccaroli (2019). Note: Non-inscripts parliamentarians are included in the computation but excluded from the chart to facilitate the interpretability.

This means that in the last five years, centre-left, centre-right and centrists have voted together for most of the votes, with occasional support – or abstentions – by the Greens and, less likely, by the British and Polish conservatives and the left. Most of the time, Eurosceptic parties, including Salvini’s Lega, Le Pen’s Front National and UKIP, were instead voting exactly the opposite. However, on many other occasions the centre-left departed from this coalition and voted instead together with the left and the Greens. On these occasions, parties on the right of the spectrum, including the centre-right, conservatives and far-right (both ENF and UKIP’s EFDD) voted in exactly the opposite way of the left. The centrists of ALDE voted occasionally with the left or the right pole. The relative distance of the dots from one another captures exactly this “uncertainty factor”. The fact that the centrists of ALDE are between centre-left and centre-right legislators means that they might vote with one or the other, more or less with equal probability. In this sense, the distance between dots can be interpreted as the ideological distance between each MEP.

The impact of the crisis on ideology

The percentage reported on the axes indicate that the two dimensions have different explanatory powers, suggesting in particular that support for European integration has become a more important dividing line in the parliament than the traditional left-right cleavage, in line with the perception we mentioned in the opening of this article. However, this has not always been the case. As Figure 2 shows, the crisis has played a very important role in this regard.

Figure 2: Main cleavages determining MEPs’ voting behaviour in the last 3 European Parliament terms

Source: Cheysson and Fraccaroli (2019).

In line with previous work on MEPs’ votes, the left-right dimension was the most relevant in the pre-crisis period. Things changed with the crisis. In 2010, as soon as the financial crisis spilled over into the euro crisis, the European dimension gained prominence.

However, not all votes are the same nor do they have the same weight. We hence inspected the distribution of votes across the two dimensions, noticing that European support mainly had an impact on budgetary votes (46% of votes determined by the European dimension are on the budget). In turn, the left-right dimension has had little impact on the budget (12%), whereas it was determinant for votes on both files with relevant legislative impacts but also for many resolutions with little or no legislative impact.

What can we then expect from the next European Parliament? It is difficult to say. As noted in a recent paper, the next European Parliament will likely be more fragmented and Eurosceptic parties will gain a larger share of seats. Given our findings, we have now a clearer idea of what to expect from Eurosceptic parties. In particular, we have shown that Euroscepticism has mainly impacted on the budget rather than ordinary legislation. Moreover, this aspect makes us reflect on how grounded as an ideology Euroscepticism is, as it is associated with the contextual position of Eurosceptic parties as opposition. This leaves the picture unclear whether as these parties’ powers expand, this may turn into a retrenchment of European institutions or, on the contrary, a re-emergence of the traditional left-right conflict.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: © European Union 2018 – European Parliament (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

_________________________________

Nicolò Fraccaroli – University of Rome Tor Vergata

Nicolò Fraccaroli is a PhD candidate in Economics at the University of Rome Tor Vergata and worked for one year and a half in the International and European Relations directorate of the European Central Bank. He graduated from the London School of Economics in Political Economy of Europe and published with Robert Skidelsky the book Austerity vs Stimulus: The Political Future of Economic Recovery (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

Anatole Cheysson – European University Institute

Anatole Cheysson is a PhD candidate in Economics at the European University Institute.