The access of interest groups to the European Commission has important implications for the legitimacy of the EU policy process. Yet there is a widely held assumption that groups representing specific interests, such as business associations, are likely to enjoy greater access than those representing ‘diffuse’ interests, such as environmental and consumer organisations. Drawing on new research, Carl Vikberg explains that although there is some broad evidence for this assumption, the picture varies substantially across different policy areas.

The access of interest groups to the European Commission has important implications for the legitimacy of the EU policy process. Yet there is a widely held assumption that groups representing specific interests, such as business associations, are likely to enjoy greater access than those representing ‘diffuse’ interests, such as environmental and consumer organisations. Drawing on new research, Carl Vikberg explains that although there is some broad evidence for this assumption, the picture varies substantially across different policy areas.

Interest group access to the European Commission is often claimed to be favourable to groups representing specific interests, like business associations, but unfavourable to groups representing broader diffuse or public interests, like environmental or consumer organisations. For example, scholars have established that interest groups representing specific interests gain more access to the Commission than do groups representing diffuse interests, and civil society organisations and trade unions have voiced concern over ‘big business’ bias in Commission expert groups. Scholarly explanations of specific interests’ higher degree of access typically suggest that they possess more technical expertise than diffuse interests do, and that the Commission demands this technical expertise to initiate effective policy.

Yet empirical findings indicate that interest group access to the Commission may be more complex than this narrative suggests. For example, research has found that access to Commission expert groups in the Directorate-General (DG) Enterprise and Industry favours specific interest groups, whereas access to expert groups in DG Health and Consumer Protection favours neither specific interest groups nor diffuse interest groups. What can account for these variations in access?

I sought to gain traction on this question by analysing the relative access of specific and diffuse interest groups in all Commission expert groups with interest group participants. For each of these 223 expert groups, I coded interest group participants as specific or diffuse interests. Organisations representing a constituency with a clear role in the production process, like business associations or trade unions, were coded as specific interests, while organisations representing a cause that is not explicitly tied to the self-interest of their members, or a constituency without a clear role in the production process, were coded as diffuse interests. I then calculated the proportion of diffuse interest groups relative to all specific and diffuse interest groups, mapped this proportion across policy areas, and assessed potential drivers of variation across expert groups.

The analyses generated two principal findings. First, in line with the conventional narrative, specific interests were indeed numerically overrepresented in most expert groups. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of expert groups across different proportions of diffuse interest access, where a value of 1 indicates an expert group where all interest group participants represent diffuse interests, while a value of 0 indicates that all interest group participants represent specific interests. Most expert groups gather around the lower end of this spectrum.

Figure 1: Share of diffuse interests in expert groups

Source: Own data based on the Commission’s expert group register.

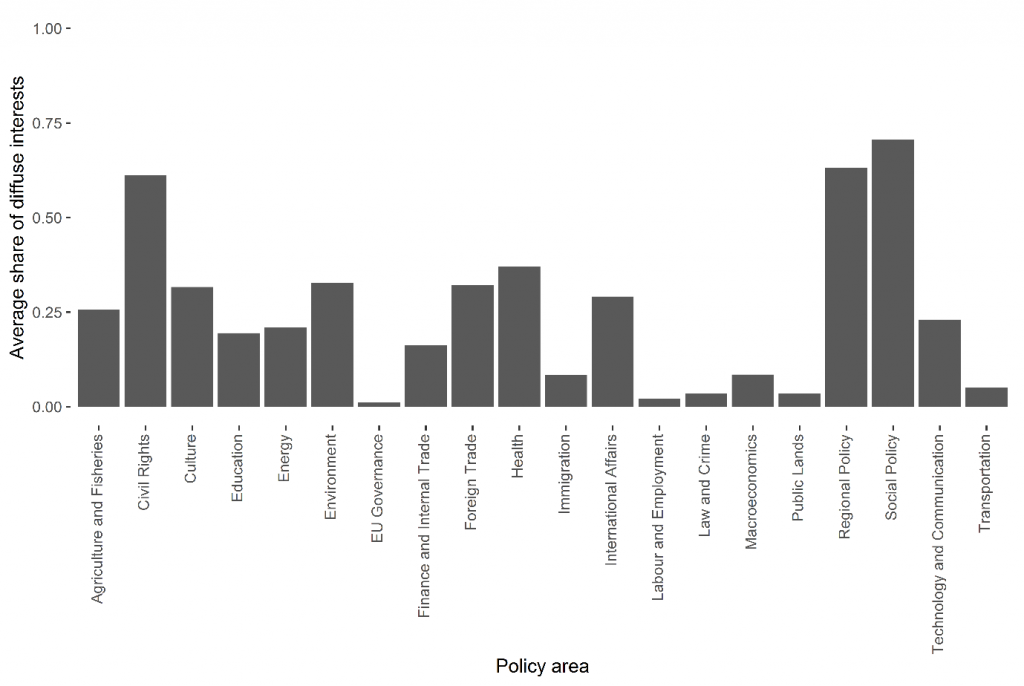

However, there were also substantial variations across policy areas, as illustrated by Figure 2. Diffuse interest group presence was particularly high in expert groups addressing civil rights issues, social policy, and regional policy. Specific interests had a particularly high presence in policy areas with a clear economic profile, but also in less usual suspects like law and crime, immigration, and EU governance. Importantly, however, the patterns across substantive policy areas should be interpreted with caution, since several policy areas contain few observations.

Figure 2: Average share of diffuse interests in expert groups across policy areas

Source: Own data based on the Commission’s expert group register.

Second, the data provided support for two potential explanations of variations in diffuse interest access across expert groups. The first explanation is based on the assumption that expert groups addressing distributive policies, specifically the Common Agricultural Policy and cohesion measures, will have a higher share of diffuse interests than those addressing regulatory policies. The proposed theoretical rationale here is that the distribution of gains from these policies is particularly visible to the general public, which incentivises the Commission to seek out information from diffuse interest groups to avoid opposition.

The second explanation assumes that expert groups run by newer DGs will have a higher share of diffuse interest groups than those run by older DGs. The proposed theoretical rationale in this case is one of path dependence, according to which older DGs were established at a time when the Commission was generally less open to diffuse interests, and whereby access patterns that privileged specific interests have taken hold. In addition to these two explanations, the analyses granted limited support to the hypothesis that expert groups in publically salient policy areas have a larger share of diffuse interests.

There are two main take-aways from these findings. First, while they do support conventional expectations of specific interest overrepresentation in access to the Commission, the findings nuance the technical logic often used to explain it. The data show extensive variations across policy areas, and expert groups in policy areas where the distribution of gains is particularly discernible have a higher share of diffuse interest participants. This supports previous findings of a Commission concerned not only with technical expertise, but also with political support among the public.

Second, while empirical patterns say nothing about whether interest group access is ‘biased’ in a normative sense, they may still inform normative evaluations of interest groups’ relative access to expert groups. In this regard, the findings paint a dual picture. On the one hand, specific interest groups are indeed numerically overrepresented in expert groups. This may be concerning for someone who considers the average representation of interests across all types of policies to be the relevant normative unit of analysis. On the other hand, there are extensive variations across policy areas, and some limited evidence of a positive association between public salience and diffuse interest access.

This may hold some slight promise for anyone who considers it normatively desirable that diffuse interest access should be higher on issues the public consider important. However, those who hold this position would most likely wish for stronger evidence of an association between salience and access.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying article in European Union Politics

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Gérard Colombat (CC BY 2.0)

_________________________________

Carl Vikberg – Stockholm University

Carl Vikberg – Stockholm University

Carl Vikberg is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at Stockholm University. His research focuses on interest group politics in international organisations.