The question of whether governments should provide financial assistance to the unemployed has proven to be one of the most heated issues in modern politics. Yet given the opposition such schemes have faced throughout history, what prompted states to introduce them? Drawing on a new study, Herbert Obinger and Carina Schmitt highlight the crucial impact the West’s experience with war during the 20th century had in motivating states to adopt unemployment insurance systems.

The question of whether governments should provide financial assistance to the unemployed has proven to be one of the most heated issues in modern politics. Yet given the opposition such schemes have faced throughout history, what prompted states to introduce them? Drawing on a new study, Herbert Obinger and Carina Schmitt highlight the crucial impact the West’s experience with war during the 20th century had in motivating states to adopt unemployment insurance systems.

Unemployment insurance was and still is one of the most contested social protection schemes. As a consequence, it was not only introduced at a relatively late stage in the development of modern societies, but is also still missing in many countries around the world.

Income support for the unemployed was highly controversial because, unlike health, work injury and pension schemes, it provides welfare benefits to able-bodied people who are capable of working. In line with the approach to welfare pursued during the 19th century, with its sharp distinction between the deserving and the undeserving poor, unemployment was typically attributed to individual characteristics such as idleness or moral misconduct, to the extent that any income support for the ‘work-shy’ was considered unfair and a reward for indolence.

In a similar vein, the then prevalent classic doctrines in economics postulated that unemployment is voluntary and mainly a matter of excessive real wages. Employers often opposed funding for a programme that would strengthen the labour movement, whereas agrarian interests considered unemployment to be an urban problem. Other critics of unemployment insurance warned of severe moral hazards and argued that the unpredictability of business cycle fluctuations would complicate any sound funding of such programmes. In other words, serious doubts were voiced as to whether unemployment is insurable at all.

This massive opposition raises the following question: when and why was unemployment insurance adopted in the Western world? In a recent study, we provide evidence that its introduction was critically facilitated by inter-state war, military demobilisation and post-war crisis.

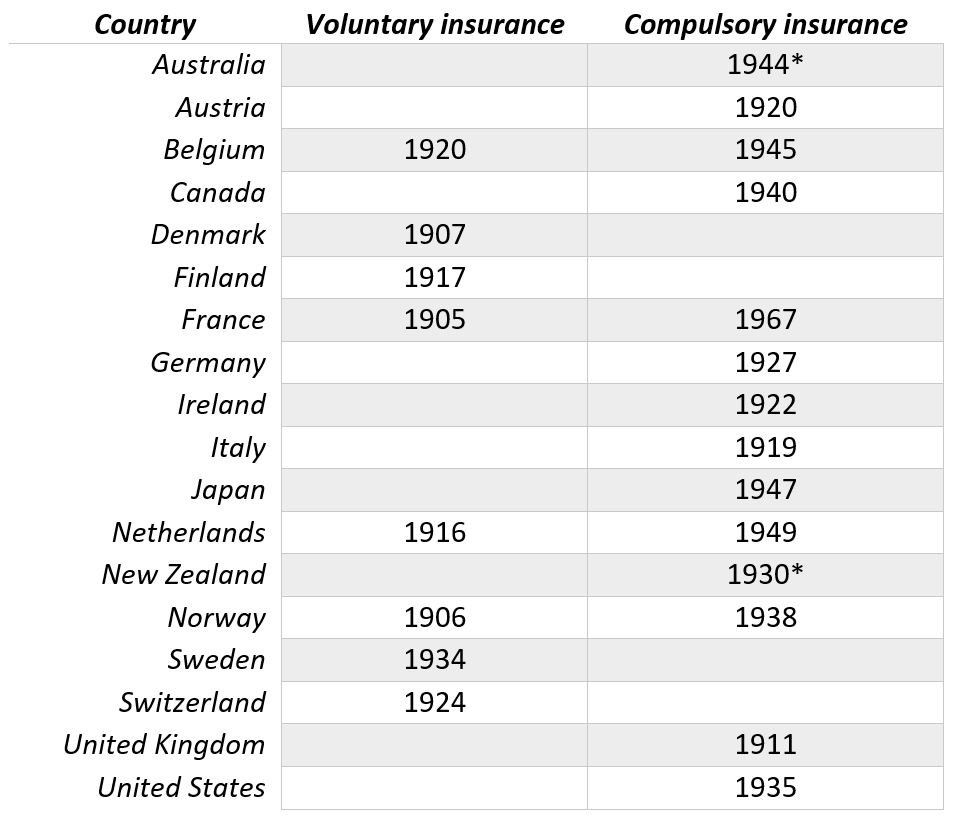

As can be seen in Table 1, most western countries introduced unemployment benefits schemes after the Great War. Only France, Denmark, and Norway had adopted voluntary systems (so-called Ghent systems) in the first decade of the 20th century, their coverage was however very low. The first country in the world to introduce compulsory unemployment insurance was Britain. However, this scheme, established in 1911 under the National Insurance Act, only protected about 2.25 million workers in sectors exposed to a high risk of unemployment. All other countries enacted their first unemployment schemes during or after the two world wars.

Table 1: Introduction of national unemployment benefit schemes

Note: Schemes marked with * refer to a targeted benefit scheme; Source: ILO (1955)

We argue that war was the crucial catalyst for states to adopt unemployment programmes. The reasons for this connection are threefold. First, the horrors of total war generated a huge demand for social protection. A common necessity for all belligerent countries was to reintegrate a huge number of soldiers into society and the labour market after military demobilisation. This included, at least for a transition period, the provision of income support in case of unemployment. In addition, there were massive lay-offs in the munitions and war-related industries. Belligerent and occupied countries that had to suffer acts of war on their home territory were particularly affected by this pressure to expand social protection, as they were also confronted with large numbers of civilian war casualties. In sharp contrast to sending troops abroad, fighting at home had a disastrous impact on the economy and therefore increased unemployment.

Second, war-induced political transformations significantly strengthened state capacities and created, in consequence, the institutional and fiscal means that enabled governments to cope with the social repercussions of war. New taxes were introduced and tax progressivity was enhanced during wartime – measures that were not fully rescinded afterwards. ‘War socialism’, i.e. the massive intervention of government in labour markets and economic policy, required new administrative capacities. Almost all western countries established social or labour ministries and created employment exchanges during and immediately after the Great War. Together with post-war democratisation, these fiscal and institutional transformations facilitated welfare legislation in the aftermath of war.

Third, massive labour scarcities caused by the draft enhanced the bargaining power of workers and unions. Additionally, the masses of returning, combat-experienced, traumatised men in combination with an increasingly radicalised working-class at the ‘home-front’ created an explosive political and economic situation. This shift in power resources and looming revolutionary threats in the immediate aftermath of war opened a window of opportunity for welfare reform.

In terms of timing, we would expect unemployment insurance to have mainly been adopted immediately after the end of a military conflict rather than during the war. In wartime, there was often no need to introduce unemployment compensation due to the massive labour scarcity and the high labour demand of the war economy. Shortly after a war, by contrast, the return of hundreds of thousands of soldiers, the influx of war refugees, the lay-offs in the munitions industry, and the economic and political crisis in war-torn economies had the opposite effect. In addition, the excessive levels of military spending that came with armed conflict likely diminished the means to finance unemployment insurance during wartime. All of this prompts the hypothesis that the extent to which a country was exposed to the horrors of war stimulated the introduction of unemployment insurance, notably in the immediate post-war period.

Findings

Using binary time-series cross-section analyses, we can show that a nation’s specific war experience (rather than war per se) matters for programme introduction. We measured a nation’s exposure to the horrors of war through an index of war intensity, which consists of three standardised components: (i) the number of war casualties measured as a percentage of the pre-war population, (ii) a theatre of war on home territory or a foreign occupation, and (iii) the war’s length.

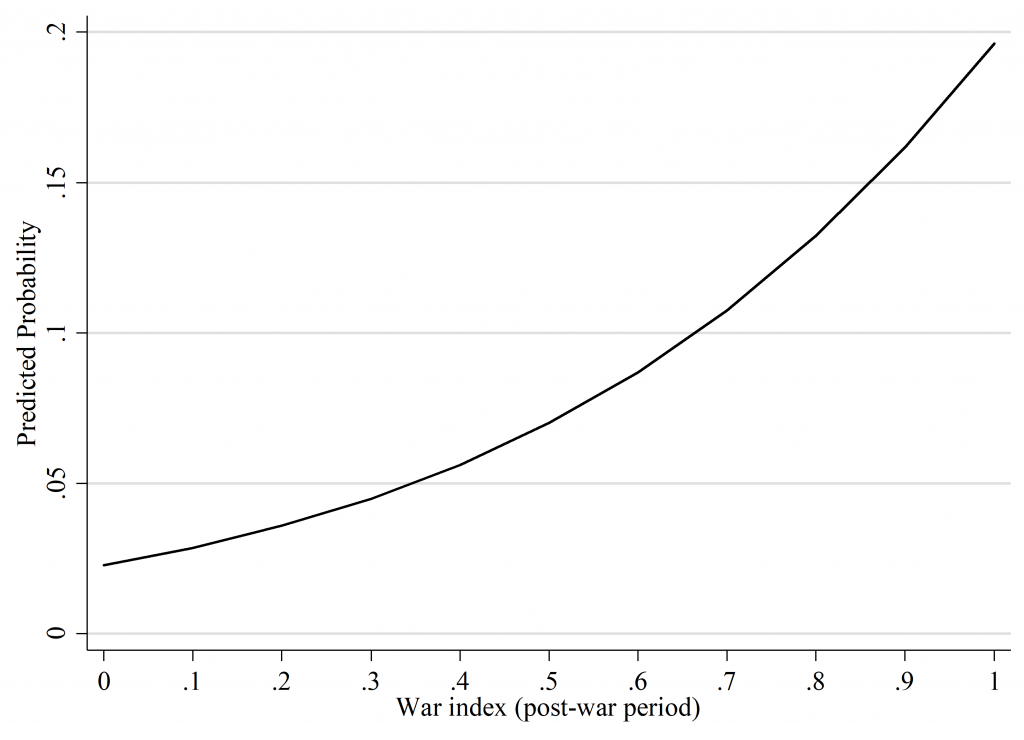

Our findings clearly show that war intensity matters for welfare reform. The higher the index and therefore the war intensity, the greater the probability for the adoption of unemployment insurance. In line with our hypothesis, this only holds true for the immediate post-war period. Figure 1 illustrates the predicted probability of adopting unemployment insurance along the whole range of the war intensity index for the immediate post war period (i.e. two years after the war). All things being equal, the predicted likelihood of a country not involved in combat adopting unemployment insurance is 2.3% compared to almost 19.6% for a nation massively affected by war. As hypothesised, the figure clearly shows that the likelihood of introducing unemployment legislation strongly increases with the extent to which a country was exposed to the dreads of war.

Figure 1: Predicted probability of implementing unemployment compensation

Note: All other variables are set at their mean

While both world wars were catalysts for unemployment insurance legislation, warfare is clearly not the only driver for the adoption of unemployment insurance. Apart from the impact of war, we found that left governments had a significant effect on the implementation of unemployment legislation. Moreover, war cannot explain the first unemployment policies everywhere. As depicted in Table 1, some countries such as Sweden, New Zealand and the United States introduced their first schemes in the 1930s. Here the key impetus was the Great Depression and the concomitant unemployment rates that skyrocketed to unprecedented levels.

The general conclusion is that national emergencies such as mass warfare and severe economic crises led to the breakthrough of unemployment insurance. The tremendous social needs created by these emergencies not only forced governments to act but also prompted ideational change and a paradigm shift in economic thinking: unemployment could no longer be considered voluntary and Keynesianism challenged the classic view that market-mechanisms always clear the labour market.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study in the Journal of European Public Policy

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Herbert Obinger – University of Bremen

Herbert Obinger – University of Bremen

Herbert Obinger is a Professor of Comparative Public and Social Policy at the University of Bremen.

–

Carina Schmitt – University of Bremen

Carina Schmitt – University of Bremen

Carina Schmitt is a Professor of Global Social Policy at the University of Bremen.