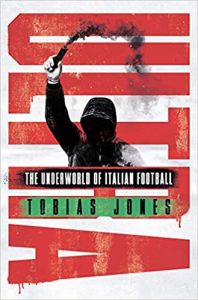

In Ultra: The Underworld of Italian Football, Tobias Jones immerses himself in the culture of Italian football ultras, exploring the rituals of different ultra groups, their infamous links with violence and contemporary far-right politics alongside the enduring left-wing identities of some ultras. Jones is an expert and sympathetic guide through this world, showing ultra culture to be as much about complex issues of belonging as it is about the love of the game, writes John Tomaney.

Ultra: The Underworld of Italian Football. Tobias Jones. Head of Zeus. 2019.

In Ultra: The Underworld of Italian Football, Tobias Jones charts a way of life reviled by polite society. Although football hooliganism and ultra culture can be found in many societies, it takes a distinctive form in Italy. As a previous author of fiction and non-fiction with Italian themes, and a devoted fan of calcio, Jones is an expert and sympathetic guide to this strange and tenebrous world. Although helpful, an interest in and knowledge of football is not required to profit from reading the book, because it is about a bigger subject: what the author describes as the ‘vanishing grail of modern life: belonging’ (70).

In Ultra: The Underworld of Italian Football, Tobias Jones charts a way of life reviled by polite society. Although football hooliganism and ultra culture can be found in many societies, it takes a distinctive form in Italy. As a previous author of fiction and non-fiction with Italian themes, and a devoted fan of calcio, Jones is an expert and sympathetic guide to this strange and tenebrous world. Although helpful, an interest in and knowledge of football is not required to profit from reading the book, because it is about a bigger subject: what the author describes as the ‘vanishing grail of modern life: belonging’ (70).

The book traces the genealogy of ultra culture, which originated in the anni di piombo (‘years of lead’) marked by political violence from the far-left and the fascist right and by Mafia murders. The ultras have a long and complex relationship with political extremism and organised crime, sometimes presenting themselves as an alternative, sometimes implicated. Early ultra groups were inspired by ‘autonomist’, left-wing ideas, but from the 1980s onwards, as youth unemployment grew and the Left lost contact with the working class, far-right organisations increasingly have dominated the curva. Jones seems unsure whether this represents a genuine mobilisation of neo-fascist ideology or merely a means for young men to signal their rejection of mainstream society. The ultras revel in the disdain which bourgeois society reserves for them. Currently, though, parties of the populist far right, such as the Lega, borrow the language and methods of the ultras to radicalise Italian politics, even if, in places such as Livorno and Cosenza, ultras maintain a left-wing identity.

The distinctiveness of Italian ultra culture rests on the choreographies conducted in the curva, which mimic martial parades and involve paper-bombs, flares, flags and banners. Ultra groups draw on a repertoire of songs based on Italian pop standards, folk tunes, arias as well as country and western ballads, with lyrics that memorialise fallen comrades and celebrate their traditions. This performance often matters more to the ultras than what happens on the pitch, more so in an era of super-rich, pampered and faithless players. Jones describes an entire lifeworld with its own morality and aesthetic. Italian ultras have developed their own literature in the form of memoirs, have published newspapers and even use their own typeface – Ultras Liberi – in which banner slogans are written. Elaborate hierarchies and decision-making structures determine what is sung and displayed.

The story ranges across Italy, examining the ultras of Juventus and Torino, Roma and Lazio, Genoa and Sampdoria, but the main focus is Cosenza, a small city in Calabria with a lower league team. Jones adopts the role of embedded reporter with the Cosentini. He joins their touring carnival of misdeeds, as they follow the club to away fixtures around the country, sharing the agonies and ecstasies of the fans. As a mob, they practise larceny and antisocial behaviour with impunity and a ‘mixture of menace and humour’ (289), goading opposing fans and the police. Jones captures the thrill of the crowd and how it offers, for some, ‘blissful erasure’, a ‘blessed moment’ and becomes a ‘living organism’ (289).

Consenza ultras avow a left-wing anarchism and see themselves as opponents of the political corruption in their own city, and as a resistance to neo-fascism and ‘territorial discrimination’ against the Mezzogiorno. Inevitably, there is a cast of larger-than-life characters including, improbably, a radical, narcissistic, football-obsessed Franciscan friar, Padre Fedele – the only thing bigger than his ego was his heart, according to his mother – who appointed himself unofficial chaplain to the Consenza ultras, gaining national notoriety.

Fighting, though, is at the heart of ultra life. Jones maintains that much of it is a show, an artifice. All parties – ultras, police and the media – have a vested interest in exaggerating the level of violence, he suggests. Simultaneously, though, he catalogues episodes of gratuitous brutality. A large part of the book is a litany of fights that end up with ultras (or police or innocent bystanders) maimed or killed. War stories are interspersed with tales of the endemic corruption and match-fixing that have been the hallmark of Italian football. Attacking referees, before, during or after matches, was a traditional ultra activity. It is implied that clubs have colluded in, or have chosen to ignore, ultra violence. For Jones, fighting is a response to existential pessimism; the ultra life offers an alternative to a secular, atomised, amoral society. According to one ultra, fighting makes him ‘feel alive in a world of the dead’ (205).

The contemporary commercialisation of football, its mercenary players, international investors and lucrative global TV rights deals have transformed the game. At larger clubs, ultras have sought a slice of the business through ticket touting, ‘security’ contracts, the selling of memorabilia and drug dealing. Refurbished stadiums and the gentrification of the game ought to signal their demise, but the ultras persist, rejuvenated by their links to right-wing politicians. Stigmatisation feeds radicalisation; bourgeois scorn confirms their convictions. Jones remains unsure whether the ultras are rascals or brutes. Or both.

In Jones’s account, ultras form a band of brothers recruited predominantly from urban working-class communities. Typically, these are ‘lost boys looking for a cause’ (113-14). Jones describes one teenager, convicted of the murder of a policeman at a Sicilian derby between Catania and Palermo, as ‘a dim underdog led astray’ (297). He recounts the (unrepresentative) tale of the grandson of a famous Hollywood composer, born in California but brought up in a posh neighbourhood of Rome, who enlisted in the Roma ultras as a way ‘to integrate, to be accepted as a local’ (58) and who rose through the ranks to become a famous capo-ultra. Many ultras come from troubled family backgrounds. Suicide is a recurring theme. The performative masculinity of the curva offers the hope of ‘rootedness and belonging’ (xii). Women are mentioned in places in the book, but their role in relation to the world of ultras is unexamined. Similarly, growing and endemic racism on the curva, while acknowledged, is not given the attention it merits.

An important and convincing theme of the book concerns how ultras give expression to campanilismo, the frequently fissiparous localism of Italian society. Its anthems are powerfully affecting. In March 2020, a viral tweet recorded the locked down residents of a Sienese street singing Canto della Verbena, a hymn to the city associated with the Palio and Robur Siena, the local football club: ‘viva la nostra Siena / la più bella delle città!’ (‘long live our Siena / the most beautiful city!’). For Jones, the Cosenza ultras express a deep topophilia, seeing themselves as embedded in its landscape, history, people and political traditions. The ultra way of life ‘is a constant expression of love for the city’ (390). Jones implies that the Left has vacated this territorial politics, leaving the ultras open to the claims of identitarian politics. If civic leaders are embarrassed by the passions of the ultras, a ‘sense of exclusion makes them feel even more integral to, or rooted in, the city’ (390). Ostensibly about football violence, this is also a book about love.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article is provided by our sister site, LSE Review of Books. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: forzaq8 (CC BY 2.0)

_________________________________

John Tomaney – University College London

John Tomaney is Professor of Urban and Regional Planning in the Bartlett School of Planning, University College London.