The Eurozone crisis increased calls for institutional reform and closer parliamentary oversight of the EU’s crisis managers. As Federica Genovese and Gerald Schneider show, the national demand for increased parliamentary scrutiny crucially hinged on the exposure to the crisis and the domestic leeway in fighting it.

The Eurozone crisis increased calls for institutional reform and closer parliamentary oversight of the EU’s crisis managers. As Federica Genovese and Gerald Schneider show, the national demand for increased parliamentary scrutiny crucially hinged on the exposure to the crisis and the domestic leeway in fighting it.

A frequent phenomenon in times of economic crisis is that the fight between contending social groups over who should shoulder the burden of adjustment frequently delays necessary reforms. The fear that the complex decision-making apparatus of the European Union would prevent the organisation from finding adequate responses to the Eurozone crisis was particularly pronounced. To the surprise of some Eurosceptic predictions, the EU was able to agree on substantial policy reforms in the midst of the recent economic crisis. What allowed for these responses? Did the macroeconomic features and set-up of the Union trigger particular parliamentary action? In a new study we demonstrate that financial crises in general, and the Great Recession in particular, have prompted many member states to strengthen parliamentary oversight through the empowerment of the EU affairs committees in their national parliaments.

However, the demand for democratic control of EU affairs is uneven across the supranational organisation, and – we argue – is a function of their embeddedness in the Eurozone and the debt of their national economy. First, the abilities of member states belonging to the Euro area and those staying outside the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) in fighting the crisis fallout differ fundamentally, as non-EMU member states can use both monetary and fiscal means to stimulate the economy. Thus, these states do not depend on supranational crisis management in times of crisis and their demand for parliamentary scrutiny should be lower than for those states that are part of the Eurozone. The demand for increased oversight in non-EMU countries, however, increases once domestic debt constrains the sovereignty in responding to a crisis, making the outsider more dependent on the decisions made within the Eurozone. Economically troubled countries within the Eurozone, by contrast, would not increase their demand for further parliamentary scrutiny in times of crisis.

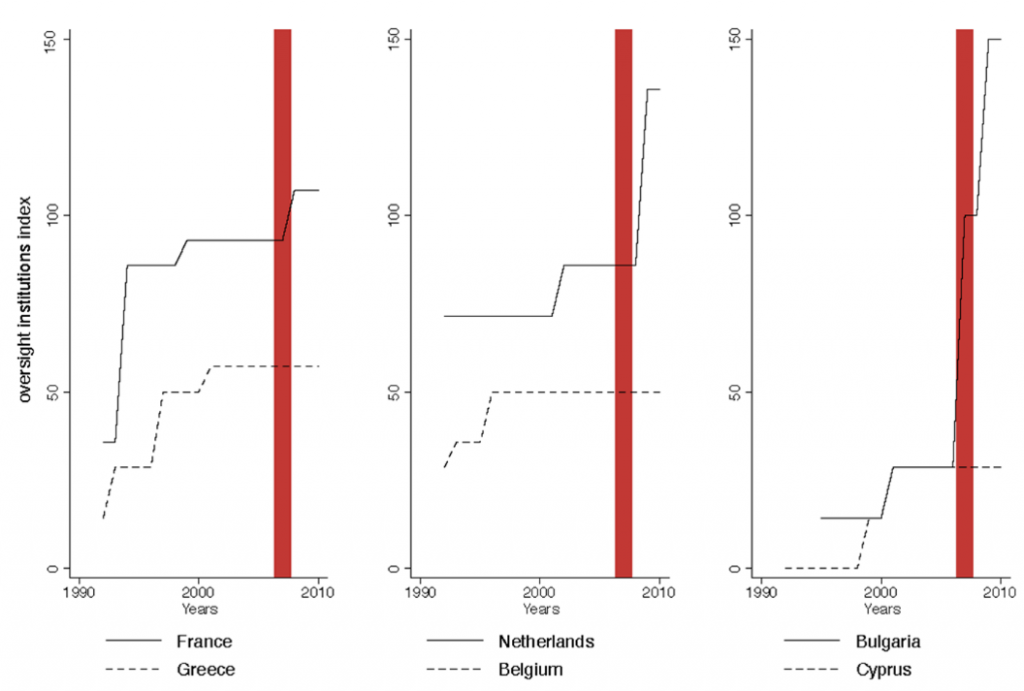

Using data on parliamentary scrutiny across Europe, we are able to confirm our double expectation that EMU outsiders are less likely to increase the monitoring capacity of their national parliaments, but that the chance of a further empowerment of the national legislature increases with growing domestic debt. Figure 1 below illustrates how selected countries have strengthened their parliamentary oversight over time. France, for instance, strengthened its oversight mechanism at the onset of the crisis while heavily indebted Greece refrained from empowering its national legislature further during the same period. A similar difference can be observed between the Netherlands, a country with a low debt level, and heavily indebted Belgium. By contrast, the non-EMU Bulgaria empowered the national legislature much more than other late-accession EMU-insider countries like Cyprus.

Figure 1: Trends on the adoption of EU oversight institutions in selected countries

Note: Lines are the country–specific trends on Winzen’s rescaled institutional oversight index. The red bar indicates the beginning of the Great Recession (2008) that led to the Euro crisis; it does not refer to country-specific crises (Bulgaria, for example, did not undergo a crisis according to Laeven and Valencia, 2012).

The exposure to the crisis also affects how parliaments evaluate the crisis. Here, we specifically focus on EMU debates to explain their discussions on EU affairs control. We argue that governments try to keep the gates closed for debates about parliamentary sovereignty at the height of the crisis. However, if they cannot prevent a debate, members of the parliament will demand more oversight power especially if the country is heavily indebted and therefore at risk of losing its governing capacity.

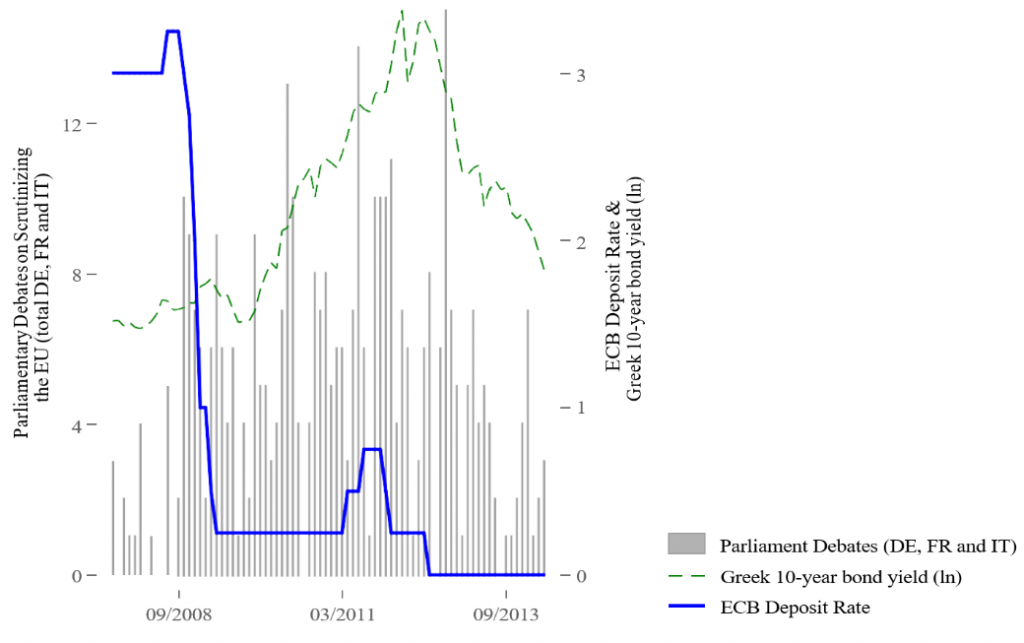

We selected three large member states – France, Germany and Italy – and examined how their parliaments debated demands for more parliamentary oversight in relation to the timing of the Euro crisis. Figure 2 shows that the monthly difference between pro- and anti-scrutiny words varies with the countries’ experience of the crisis. Significantly, support for further parliamentary powers decreased with the intensification of the economic troubles. In 2012, when the crisis was at its climax, the support for increased parliamentary support flattens out. Additionally, the pro-oversight faction is more active in the Assemblée Nationale, the national legislature of the less debt-constrained France, than the Parlamento italiano.

Figure 2: The Great Recession and Support for Scrutiny of EU Institutions

Note: The plot shows the variation of pro-scrutiny sentiment as recorded in the collected texts of the French, German and Italian parliamentary debates (black lines). The graph also shows the Greek 10-year bond yields and the ECB deposit rate as the two main indicators of the Euro crisis.

In sum, the evidence demonstrates that political and economic interests of domestic actors have shaped the legislative response to the Eurozone crisis. While such responses are probably not a sufficient antidote against Eurosceptic populist parties, they at least show that crises can strengthen rather than weaken democratic institutions.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in The Review of International Organizations

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Federica Genovese – University of Essex

Federica Genovese – University of Essex

Federica Genovese is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Government at the University of Essex.

–

Gerald Schneider – University of Konstanz

Gerald Schneider – University of Konstanz

Gerald Schneider is a Professor at the Department of Politics and Public Administration, University of Konstanz, Germany.