In The New Despotism, John Keane revives this term to examine how the ‘new despotism’ functions today through qualitatively different characteristics and processes to its older forms. As the book skilfully identifies how the new despotism thrives on ambiguity above all, this is a perceptive study that will shift the analytical lens through which despotic regimes are viewed, writes Gergana Dimova, and offers a warning to the complacency of liberal democracies.

The New Despotism. John Keane. Harvard University Press. 2020.

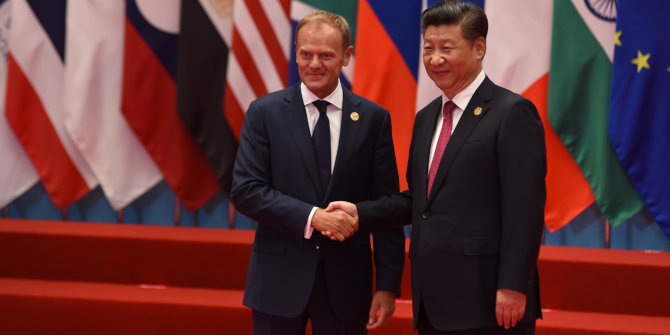

I had a piercing toothache when I started reading The New Despotism, but I became numb to the physical pain halfway through the book. That is because the text unsettled me in a profound way, despite the fact that I have long been accustomed to pouring over John Keane’s work and I relish its rebellious nature. Mine is not intended to be an isolated experience. The author himself professes that the term ‘new despotism’, probably best exemplified for Keane by China, which is mentioned 206 times in the book, ‘aims to unsettle orthodox taxonomies, old-fashioned ways of ordering things. It urges readers to think in fresh ways, to see the world with new eyes, to arouse different feelings, to pry open unfamiliar horizons of action’ (13). It delivers.

I had a piercing toothache when I started reading The New Despotism, but I became numb to the physical pain halfway through the book. That is because the text unsettled me in a profound way, despite the fact that I have long been accustomed to pouring over John Keane’s work and I relish its rebellious nature. Mine is not intended to be an isolated experience. The author himself professes that the term ‘new despotism’, probably best exemplified for Keane by China, which is mentioned 206 times in the book, ‘aims to unsettle orthodox taxonomies, old-fashioned ways of ordering things. It urges readers to think in fresh ways, to see the world with new eyes, to arouse different feelings, to pry open unfamiliar horizons of action’ (13). It delivers.

If you ever held the assumption that despotic regimes are old-fashioned, technologically ‘backwards’ countries, where old men rule over poor and uneducated people, you are in for a ride. In his new book, Keane revives the notion of ‘despotism’, but he calls it ‘the new despotism’, because it contains some qualitatively different characteristics. To begin with, the author dispels the myth that ‘despots rule by killing or repressing people against their will.’ Admittedly, violence has not disappeared entirely in the new despotism. In Kazakhstan, for example, human rights workers have been recorded as being marked with an ‘X’ for censorship (176). In Singapore, police search the homes of those deemed to be risks to ‘national security’ without warrants. Yet, a new element in the new despotism is that violence is much more muted and conscious, replacing intimidation and surveillance with seduction.

The strength of the new despotism comes from its skilful use of the media, and that use goes far beyond the familiar dissemination of ‘fake news’ and the slandering of opponents. Rather than hiding from public view, the new despotism embraces communicative abundance and intrumentalises it to the fullest degree. Leaders’ media appearances are lavish, meticulously choreographed affairs. It could be said that the new despotism stages non-stop theatrical spectacles projected to the whole nation. Grand infrastructure projects are one key prop in this theatre of self-aggrandisement.

The media are only too happy to be weaponised by the new despotism as they get generous tax breaks and coveted exclusive licenses in return. It’s a win-win-win situation: the new despotism benefits from the fruits of this deception, the media conglomerates make money and the public feel entertained and pandered to. This configuration seems like a Pareto optimal equilibrium. It is eminently more sustainable than the far less media savvy communist regimes, where the Party leaders gave bleak performances, the state media was cash-starved and the audiences were irreversibly bored.

However useful, the media are only part of the new despotism’s arsenal of seduction. If I had to find one word that explains the value added and the mastery of this book, it would be ‘ambiguity’. The book manages to explain how new despotism thrives on ambiguity and what these ambiguities are. One particular strength of the new despotism – and the first ambiguity– comes from its ability to successfully blend traditional local ways of doing things with an adoption of the most modern practices of democracies. This is an important observation for Keane to make because previous failed attempts at democratisation have shown that threading the line between old customs and contemporary Western techniques for governing is a highly precarious balancing act. Having read the book, we now know that the new despotism seems to excel more in this art than democracy-exporting countries. This combination of local ways and Western practices is very misleading for the new despotism’s subjects and no less confusing for outside observers.

The second ambiguity that Keane reveals is the new despotism’s complicated relationship with democracy. On the one hand, it derives pleasure from democracy’s failures, and loudly points them out. At the same time, it examines democratic achievements and consciously tries to replicate them. Mimicking democratic arrangements, and sometimes actually adopting them, is a key element of ‘seducing’ the public. Some of the procedures that the new despotisms take from democracy’s playbook include: ‘e-consultation exercises, online public forums, and small-scale informal consultations conducted by government ministers and known as Tea Sessions, Dialogue Sessions, Policy Feedback Groups, and Policy Study Workshops. The rulers operate Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts’ (95). These innovations make the public more vested in the ruling regime. They make them accomplices.

Mimicking, or even adopting, democratic procedures is a key ambiguity in the arsenal of seduction, it seems to me. The public can never have enough information to figure out to what extent democratic rule extends from local initiatives to a systematic practice. It is also often hard for any single citizen to tell a free and fair election from a manipulated one. All the citizens see are clear signs that the government is listening to the people. This impression is heightened by the media, which invariably tells them that the people are important. In a way all too familiar to scholars of populism, the new despotisms ‘regularly deploy the rhetoric of “the people” and refer constantly to them as the presumed source of sovereign authority’ (82).

To top it all off, the new despotism makes sure to demonstrate the use of the full power of the law and legal order. The catch – and this is yet another ambiguity – is that leaders uses the law selectively to fight opponents, while subverting the law to shield themselves and their clique. While the former is plain to see, the latter is often impossible to prove. It seems that the new despotism has planted all these hints, intimations and ambiguities to mislead the public. The subjects are one step away from willingly surrendering themselves to ‘voluntary servitude’, as Keane puts it (108).

But to make that final step, the public needs an internal motivating factor. It needs to feel that there is something in it for them. This something needs to be individual and tangible; it needs to be something material. The public needs to be not only cajoled; it also needs to be bribed. Those bribes come in the form of the enjoyment of small material possessions and luxury experiences, such as vacations and hobbies. Perhaps the most stinging rebuke in this book is aimed at the middle classes, who are ‘prepared to trade some liberties for comfortable peace and quiet’ (237).

The book tells us that it is quite possible, and even probable, for well-educated, well-travelled and ‘well brought up’ people to give up their ability to think critically for the opportunity to frequent fancy airport lounges, hotels and shops. Instead of inspiring ideals, driving progress and defending the less fortunate, these middle classes embrace cynical morals and fickle pragmatism. In the best possible scenario, they will forsake morals for professional prestige, not for replicas of Louis Vuitton bags.

On the surface, the new despotism’s middle classes seem like opportunistic intellectuals turned ultimate consumerists. But Keane underscores that they lead a comfortable, rather than a luxurious, life. It seems that this ambiguous situation – yet another ambiguity – puts the middle classes at risk. Looking up to the unattainable riches of the elites and looking down upon the insufferable misery of the poor, the survival instinct of the middle classes seems to kick in. It leads them to be satisfied with the small but stable private property they have rather than chase bigger but elusive riches. Thus, the middle classes have consciously or subconsciously become the beacons of the seductively repressive new despotism. And while their numbers are small, the book tells us, their importance is big, because they are visible. Their life is up for show, and it is meant to demonstrate that it is not only the ruling elite that can live a relatively good and stable life. The implication, it seems, is that poverty is a personal failure, not the new despotism’s fault.

Like all things in the new despotism, this statement – that poverty is an individual, rather than the regime’s, failure – is half-true and half-false. By laying it all out, Keane has masterfully uncovered yet another source of ambiguity. The true part of it is that in a state capitalist economy, which the author believes the new despotism is based upon, the small business is market-driven and is open to all entrants. The false part of this account is that big business is entirely under state patronage, which precludes access to people not affiliated with the political elite.

The half-true and half-false nature of economic relations is further complicated by the fact that all economic relations are based on networks of mutual favours. While this system of favours has often been analysed before (e.g. Alena V. Ledeneva, 1998), Keane goes one step further. He writes that the system creates enormous anxiety and uncertainty – and, yes, this is also an ambiguity – as it is never clear whether you would know ‘the right person’ for every emergency you run into. Instead of feeling repulsed by such a system, the people entangled in these networks feel a sense of solidarity as everyone is an accomplice, and a sense of relief that they have managed to navigate and survive these ambiguities for so long.

A key feature of the new despotism is its quietness. Unlike in Mussolini’s Italy, Hitler’s Germany and Mao’s China, public expressions of celebration and loyalty are discouraged. In the new despotism, ‘flesh-and-blood citizens are expected to stay quiet, locked down in private forms of self-celebration’ (97). For example, ‘in Tajikistan, which bans lavish private gatherings on the grounds that extravagant parties strain family budgets, a Dushanbe resident was fined for hosting friends at a local restaurant to celebrate his twenty-fifth birthday’ (97). It seems to me that being quiet is important for the state of ambiguity to perpetuate itself. If people get together, they will compare notes; they will exchange stories. Isolation (here conceived of before the widespread lockdown in response to COVID-19), especially in the company of small material comforts, probably nourishes self-congratulation and self-regard.

The insights outlined above, while not exhaustive, are indicative of the outstanding contribution that this book makes. Revealing combinations of motives, blends of practices, mixtures of economic structures, fluidity in relationships, duplicity in using the law and the media – in short what I have here termed ‘ambiguities’ – requires a high degree of perception and an utter lack of dogmatic and stereotypical thinking. This book will undoubtedly shift the analytical lens through which we view despotic regimes.

Why is this important? If Keane is correct that the new despotism is more flexible, subtle and efficient than we had suspected (24), then it can overcome various crises. As such, the new despotism is less prone to implosions reminiscent of the Soviet Union or breakdowns as witnessed in Latin America. If it is that durable, it constitutes an attractive alternative to liberal democracy. This means that the self-regard, the feeling of invincibility and the arguable complacency of such democracies are misplaced. You have been warned.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article is provided by our sister site, LSE Review of Books. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: FelixMittermeier from Pixabay

_________________________________

Gergana Dimova – University of Winchester

Gergana Dimova is an Associate Lecturer at the University of Winchester. Previously, she was a Jeremy Haworth Research Fellow at the University of Cambridge and a PhD Candidate in Political Science at Harvard University. Her most recent book is: Democracy beyond Elections: Government Accountability in the Media Age.