Representatives from 17 Central and Eastern European countries are set to meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping in April at a ‘17+1’ summit. Daniel Quirk writes that the summit might reinvigorate EU concerns over Chinese ambitions in Europe and could motivate EU officials to continue advocating a stricter approach toward China-EU relations.

Representatives from 17 Central and Eastern European countries are set to meet with Chinese President Xi Jinping in April at a ‘17+1’ summit. Daniel Quirk writes that the summit might reinvigorate EU concerns over Chinese ambitions in Europe and could motivate EU officials to continue advocating a stricter approach toward China-EU relations.

The last decade saw significant inconsistencies in China-EU relations, as the EU oscillated between competition and cooperation with China due to the lack of a united strategy. The EU’s indecisiveness inhibited its ability to respond to China’s growing presence in Europe until last year, when the EU adopted a sterner strategy by labelling China as a ‘systemic rival’.

This new approach of being more confident in challenging China may see a more stable China-EU relationship emerge, with both parties having a greater sense of where each other stands. The clarity arising from this means the EU and China will be better able to identify areas where there is realistic potential for future collaboration and areas where interests clearly diverge, thus laying the initial foundations of a more consistent relationship.

However, whilst the relationship may become more predictable in the long-term, optimism for improved relations will likely be limited. The EU is open to some cooperation with China in mutually strategic areas due to the deterioration in relations with the United States, but persisting concerns in Brussels over Chinese intentions will mean that tough rhetoric towards China will also continue.

The EU seeks to limit the extent of Chinese influence within member states and the eastern neighbourhood, as well as monitoring China’s growing global presence. Thus, China-EU relations in the next few years will largely remain strained despite some symbolic collaborations resulting from a temporary mutual need to uphold globalisation in the face of President Trump’s isolationism.

Old challenges, new approach

From 2010 to 2016, the EU was accused of burying its head in the sand in relation to the rise of China and increasing Chinese investments within Europe. Despite China’s leadership change in 2013 and President Xi Jinping advocating a more ambitious global agenda, the EU was slow to react.

The case of the Budapest-Belgrade railway brought to light the EU’s unpreparedness in dealing with China and saw the EU Commission and Hungarian Government enter into disagreement over favourable contracts being awarded to Chinese companies. This raised concerns that China was encouraging division and undermining regional norms, which was further enhanced by worries of strategic European technology companies being acquired by China.

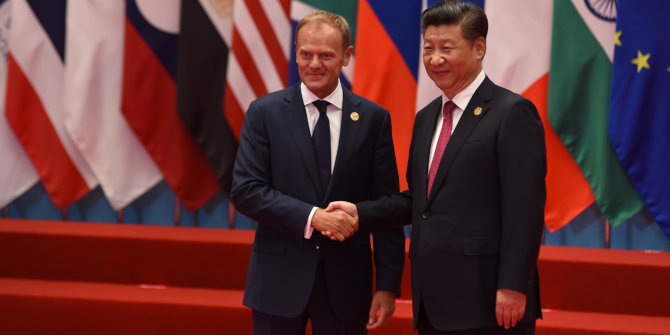

Donald Tusk, then President of the European Council, with Xi Jinping, President of the People’s Republic of China, in September 2016, Credit: European Council President (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In 2016 the EU made a modest attempt to respond to China’s foothold in its member states and the Balkans through the ‘New EU Strategy on China’, switching from investment competition to instead cooperating with China as a method of mitigating Chinese activities. Following the Belgrade-Budapest Railway controversy, the EU-China Connectivity Platform was established to integrate the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative with the EU’s Trans-European Transport Network, thus allowing the EU to exert greater oversight and regulation implementation within projects receiving Chinese assistance.

March 2019 marked a significant break from the EU’s traditional approaches towards China with a distinctive change in rhetoric. Shortly before the annual EU-China High Level Strategic Dialogue Summit, the European Commission unexpectedly recommended to the European Council that China be labelled a ‘systemic rival’.

Whilst many factors contributed towards this decision, the influence of Donald Trump’s presidency cannot be understated, with the EU recognising the need to develop more independence from the United States in foreign affairs. Signs that the Sino-US Trade War had begun to hurt the Chinese economy may have given the EU confidence that the time was right for a change in strategy towards challenging China for a more reciprocal relationship.

This sterner approach appears unlikely to shift anytime soon as the new generation of EU leaders have made clear their views on continuing a harder line on China. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is a strong proponent of the transatlantic partnership and recently stated in reference to China that whilst cooperation is possible on the environment, the EU will “never forget where we came from and which side of the table we are sitting’.

She also raised human rights and cyber security as areas which complicate the EU-China relationship. Similarly, the new High Representative of Foreign Affairs, Josep Borrell, has urged EU members to bolster activity in the eastern neighbourhood to counter the presence of China. Thus, EU officials will continue this new approach of applying pressure onto China for a more equal relationship which protects EU interests.

The dragon in the East

An issue which will remain prevalent in the minds of European policymakers in the coming years will be the ‘17+1 Initiative’. Established in 2012, the initiative is a multilateral dialogue platform for China and Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries to discuss shared interests, facilitate exchanges and synergise development projects. However, the platform has been accused of being a ‘trojan horse’ intended to divide the EU internally and reduce its ability to challenge China on issues such as human rights. Concerns over both EU and non-EU CEE states competing for Chinese investments partly contributed to the development of the EU’s new critical approach towards China.

In recent years, the 17+1 Initiative has been considered a relatively ineffective platform due to the disappointing economic impact it has had on increasing trade between China and CEE countries. Until now, its major successes have been enabling people-to-people exchanges in areas such as local government, tourism and culture.

Conversely, such criticisms have understated the significance of the 17+1 Initiative by suggesting that it has been unsuccessful based on purely economic outcomes. In contrast, the initiative is relatively new and has spent recent years establishing institutions and bodies to enhance China-CEE cooperation. As such, time will tell whether the platform has succeeded in its aims and therefore the 2020s may see results in 17+1 objectives which contrast with EU interests.

This year’s 17+1 Summit in China will be unique as President Xi himself will be presiding over the meeting, replacing regular attendee Premier Li Keqiang. The change in representation could signal a Chinese attempt to renew impetus behind the sluggish platform due to deteriorated Sino-US relations necessitating closer cooperation with European states. The EU Commission will be monitoring developments at the summit particularly closely given Xi’s attendance and it is possible that this year’s meeting might reinvigorate EU concerns over Chinese ambitions if major changes are proposed.

EU Commission officials will also be frustrated by the European Council’s recent foot-dragging on Balkans enlargement which pushes candidate states towards China. The persistence of perceived challenges presented by the 17+1 Initiative will therefore motivate EU officials to continue advocating for a stricter approach towards China.

Optimism for China-EU collaboration?

Despite continued challenges, there are sporadic opportunities for China-EU cooperation in strategic areas. In November last year, an agreement on geographical indicators for 200 European and Chinese goods was agreed after years of negotiations. Both sides are also working on a long-awaited Comprehensive Investment Agreement which is due to be complete by the end of 2020. Although progress has been difficult, it is likely that the agreement will be finalised on time, albeit in a less comprehensive manner than originally intended, in an effort to demonstrate a shared commitment to upholding globalisation against the policies of Donald Trump.

However, whether this impetus behind China-EU collaboration can endure beyond 2020 is questionable. Whilst Trump’s presidency has motivated greater engagement between the EU and China in recent years, limited cooperation on shared interests has been uneasy due to diverging principles. Issues on market access reciprocity, Chinese acquisitions and human rights will continue to inhibit significant long-lasting breakthroughs in China-EU cooperation despite these symbolic agreements. Thus, the EU’s sterner approach and selective engagement with China will likely continue beyond the Trump presidency as the EU continues to forge a more independent global role vis-à-vis China and the United States.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Daniel Quirk – Peking University (PKU)

Daniel Quirk – Peking University (PKU)

Daniel Quirk is a Yenching Scholar at the Yenching Academy of Peking University (PKU) in Beijing. His research focus is on China-EU-UK trilateral relations.