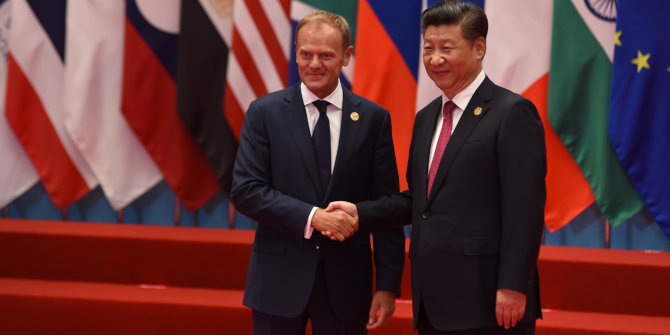

The tech rivalry between China and the United States has been characterised by some observers as a ‘Digital Cold War’. Dimitar Lilkov argues that in the technological arms race of the future, the EU may quickly find itself falling behind.

The tech rivalry between China and the United States has been characterised by some observers as a ‘Digital Cold War’. Dimitar Lilkov argues that in the technological arms race of the future, the EU may quickly find itself falling behind.

In a seminal article, Swedish polymath Nick Bostrom posits the ‘vulnerable world’ hypothesis. It is a complex premise which assumes that the chance of a destructive event occurring globally is quite likely if technological advancement continues in a prolonged timeline. He compares human progress to drawing different balls from a giant urn – most of them are beneficial or mixed blessings but there are also ‘black ball’ events which might destabilise civilisation. According to Bostrom, the preventive mechanisms against a potential technological or military doomsday scenario range from ideal global cooperation to limiting the production of certain technological items.

This is indeed a bleak view, which some might dismiss as yet another apocalyptic prediction. If you observe the global digital landscape, however, you might sense a storm brewing. A Digital Cold War is escalating between two economic giants whose digital juggernauts are dominating global supply chains and registering astronomical profits. Chinese surveillance technology has reached more than 80 countries in Asia, Africa and even in the heart of the EU. In parallel, private companies like Palantir secure lucrative contracts with the US government for monitoring internet traffic, combing terabytes of data and providing behavioural insights on a staggering scale.

The digital authoritarianism doctrine of the Chinese Communist Party is growing in appeal internationally, while unrestrained data monopolies from Silicon Valley excel at what they do best – accumulating data and acting as gatekeepers to the online world. The whole model of Internet governance and international cooperation in the technological domain has become defunct – you can`t replace the engine of an old VW minivan with a small-scale nuclear reactor and expect to navigate it safely on the highways.

The crippled shepherd

The only geopolitical actor actively working on limiting the negative externalities of a free-for-all technological race is the European Union. In recent years, the EU has tried to solve some of the most complex challenges when it comes to protecting user privacy, fighting malign disinformation or trying to restrain unlawful digital surveillance. The Old Continent has made an ambitious attempt to pioneer the golden global standard when it comes to legislation for the digital domain.

This effort has been laudable, but the framework remains patchy and constantly in the making. Two years on, the landmark GDPR has reshuffled the deck but the Big Tech platforms have aptly adapted to the new situation, while national data protection authorities can’t cope due to their small size and embarrassing budgets. Key words like ‘AI’ or ‘disinformation’ garnish many discussions in Brussels, but are mostly centred around broad frameworks and lofty clichés generated by the US tech lobby in order to dominate the discussion. Lastly, even if binding regulation comes in place, this will take several years and will likely be too little, too late.

Image by Pete Linforth from Pixabay

Regulation alone will not hold unless this continent improves its own global standing on digital infrastructure, breakthrough innovation and the strength of its technological companies. At present, this is sadly not the case. If we look at digital company market valuations, Europe doesn’t even make it in the Top 20. Not surprisingly, the 2018 French AI strategy gloomily states that France and the EU might become ‘digital colonies’ due to external tech dominance. Similar caution about the EU lagging behind has also been expressed by Chancellor Angela Merkel.

The problem here is not economic competition as such. The problem is that we are entangled in an ongoing cyber war where there are no Geneva conventions and where the terms of engagement are still blurry. The question of technological strength is essential for both the economic prosperity and the personal security of European citizens.

Strength as a shield

Innovation and world-class technology have been one of the main ingredients behind Europe’s geopolitical weight – after all, a continent comprising just 7 per cent of the world’s population is generating close to a quarter of global GDP. Europe has played an active part in setting global technological standards due to market power and international influence. Unfortunately, the EU’s sway in this arena is fading and you can’t expect the world to remain bound to an old dynamic.

European leaders should finally commit not to piecemeal initiatives but a comprehensive strategy for ensuring the technological clout of the Union. This would mean recognising the question about 5G infrastructure as both a technological and national security priority where the EU should go big or go home. This would mean pooling additional resources in the digital domain and coming as close as possible to a federal programme for continental cooperation. It is infuriating that the proposed long-term EU budget for digital competitiveness has been slashed by national leaders in the latest negotiations. Politics and compromise still keep the Union partly glued to the 20th century, while aggressive global actors are trying to plan decades ahead.

Recently, there have been some positive signs that Europe is finally waking up. The economic bloc is thinking about how to reduce its dependence on third countries for critical raw materials and how to become a global supplier of advanced battery cells. There are high expectations for the European cloud infrastructure initiative (Gaia-X) and the establishment of a single European market for data as a boost to industry across the continent. However, a huge effort (and corresponding funding) is still needed in the domain of cybersecurity, 5G infrastructure, artificial intelligence and the further integration of the European Digital Single Market.

Strength can be the only viable shield for the EU in the technological domain. European leaders should resist the urge to hide behind toothless documents or announce bombastic plans which carry more PR value than actual benefit. Remember the time when France and Germany launched an initiative to compete with Google and have a truly European search engine?

The blue flag draws a black ball

There is a growing possibility that we might see the European Union losing the technological race in the foreseeable future. Why is this a potentially catastrophic scenario for the economic bloc? First, the EU would lose its ability to influence global tech policy and prevent a race to the bottom when it comes to AI-enhanced surveillance, the unrestricted exporting of dual use technological items or the proliferation of lethal autonomous weapons. The global system will be heavily tipped toward either a more authoritarian or an unregulated Wild West scenario on the digital front. This would also mean that vital cooperation between global actors holding advanced cyber capabilities would become extremely difficult, which is a serious security risk on its own.

Second, if the EU doesn’t revive its drive for technological leadership and industrial strength by effectively pooling its resources, it will find itself dwarfed by North America and Asia. The US will provide the software, China will provide the hardware, and Europe, embarrassingly, will only provide the data. This would only lead to the geopolitical irrelevance of the European Union and a heavy hit on the economic prosperity of its citizens.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Dimitar Lilkov – Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies

Dimitar Lilkov – Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies

Dimitar Lilkov is a Research Officer at the Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies based in Brussels.