On 6 October, the European Commission released its enlargement reports, tracking the progress of countries aiming to join the EU. Florian Bieber writes that while the reports were longer than ever, the details drown out the bigger picture. He argues the reporting process should be reformed to better outline priorities, highlight the causes of problems, and make concrete proposals for the next steps in the accession process.

The release of the EU’s enlargement reports has moved from being a top event for the countries involved to a non-event, in thousands of pages. Declining interest in enlargement is not the only reason for this – it also reflects the reporting process itself.

For years, the annual reports on what used to be called ‘progress’ towards EU membership were much anticipated documents, mulled over by the media, trumpeted by leaders to celebrate their successes or used by the opposition to criticise governments for their shortcomings. Not anymore. EU integration is low on the agenda in most countries of the region: with the exception of North Macedonia and Montenegro, the reports received lukewarm attention this year.

The reports released on 6 October should have mattered. They are not only the first round of reports of the new European Commission, but were drafted under the watch of the Hungarian Commissioner for Neighbourhood and Enlargement, Olivér Várhelyi, whose close ties to the Orbán government have raised more than a few eyebrows. Furthermore, the reports were initially due in May, but were postponed at the last minute.

The reports are of biblical proportions. Each country is discussed in greater detail than ever on around 100 pages, thus journalists and observers had to go through more than 600 pages of reports on the state of enlargement in the Western Balkans. This is a lot of trees, but does it make a forest? The new reports appear to address some of the earlier criticism that they lack detail and miss out on important developments, especially weaknesses and shortcomings. The sheer volume of the reports now makes them more comprehensive and most important developments in what has been a turbulent year were caught. Yet, this does not add up to a clear picture of how the Commission sees the region. The details drown out the big picture.

A new methodology launched to great fanfare in February 2020 to appease French concerns about enlargement is not very visible in the new reports. According to the new methodology, progress is in principle linked to concrete benefits, and a lack of progress or backsliding is supposed to have consequences. The reports instead muddle along while interpreting the overall picture is left to the commissioner. This is an opportunity missed to reframe the reports with greater clarity, rather than simply making them more comprehensive. The frustration of the Commission with governments in the region, however, is clearer than it has been before.

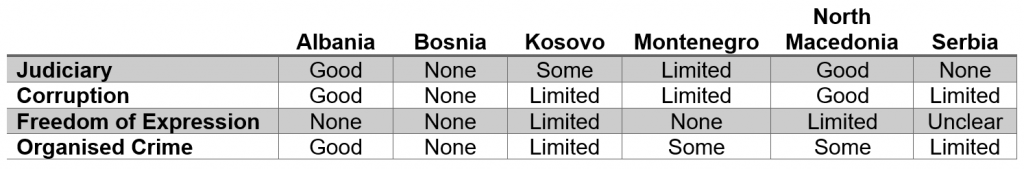

For example, for Serbia, the report notes that the Serbian government “continued to declare European integration as its strategic goal,” making clear that this is largely a declaration rather than a reality. Yet, the reports and the summary remained vague. The degree of progress is listed in some key fields, but the choice of what to include is relatively arbitrary (why only freedom of expression, not civil liberties?) and even the form of assessment is not used consistently throughout, making comparisons difficult. The table below highlights the overall picture in the fields where the general communication does discuss the countries side by side.

Table: Level of progress among the countries contained in the 2020 enlargement reports

Note: Progress is indicated as ‘good progress’, ‘some progress’, ‘limited progress’ or ‘no progress’. For ease of reference ‘no progress’ is stated as ‘none’ in the table.

The overall direction of the reports in regard to rule of law and democracy, vagaries and inconsistencies not withstanding, is clear, Bosnia has made the least progress in the eyes of the Commission, followed by Serbia. Montenegro and Kosovo are nearly tied with a small degree of progress. Finally, Albania and North Macedonia have become the front runners in terms of overall progress.

Yet, the reports do not capture the backsliding that has occurred in several countries, including in Serbia and Albania during the pandemic and before. Backsliding or regression still does not seem to be part of the Commission’s vocabulary, so the report for Albania notes that there is “no progress” in regard to freedom of expression, when there have been arrests and sentencing of journalists and civil society activities over the demolition of the national theatre during the height of the pandemic. Even where the reports capture the problem, the remedies are vague and bland.

The Commission’s annual reports should be adjusted to the crux of the new methodology that intended to render the process more political. This means outlining priorities, highlighting causes for deficiencies and problems and making concrete proposals for the next steps in the accession process. It is a pity that the single most comprehensive instrument for the EU’s political assessment of candidate members remains so underexploited.

While the reports have moved closer to capturing the problems of the region than earlier reports, they are still lagging behind in capturing the decline of democracy and rule of law in most countries and offer too little analysis to show a path forward. Ultimately, the reports are a PR disaster for the EU in the Western Balkans. They are obscuring the real picture by offering too much detail and too little clarity. With reports like these, one can expect many thousands of pages of virtual paper to be filled for many years to come on enlargement in the Western Balkans.

Note: Several members of the Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group (BiEPAG) contributed to the analysis presented in this article. The article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council