In The European Central Bank between the Financial Crisis and Populisms, the authors Corrado Macchiarelli, Mara Monti, Claudia Wiesner and Sebastian Diessner unveil the problematic relationship between the European Central Bank and European politics, and especially the populist and sovereigntist threats to its legitimacy and independence. It reveals how at times the ECB has had no choice but to make difficult decisions that impinged on the responsibilities of fiscal authorities to safeguard the European project, arguably going to the very limits of its mandate. This fascinating book is essential reading for those wanting to understand the difficult relationship between unelected central bankers and elected politicians, writes Lorenzo Codogno.

The book looks at the European Central Bank and examines the policies that tried to govern the fallout from both the economic and political consequences of the financial and sovereign debt crises, dissecting a decade of financial, economic, and institutional developments in Europe. It does that by focusing on the questions of democratic legitimacy and public reception.

It argues that the ECB was forced to act as “quasi-fiscal” and “political” entity, going well beyond the use of unconventional tools, to fill the institutional void left by an “incomplete union”. This included questions of an existential nature such as addressing the risk of default by one of its member states.

In its first ten years of activity, the ECB managed to become an anchor of relative stability after having borrowed from the inflation-fighting credibility of the Bundesbank and enjoyed broad-based consensus. In the decade that followed, the ECB was dragged in front of the German Constitutional Court countless times. Meanwhile, the ECB and several national central banks in the euro area faced populist pressures from national governments or opposition parties that criticised their decisions. The book admits that it is difficult to detect simple causalities and immediate relationships between crisis management and the rise of populism. However, “there are clear indicators for the euro crisis and the austerity measures having had a negative impact on citizen support and satisfaction with democracy”. In fact, the picture is much more nuanced than this clear-cut temporal split, but the book tries to distil the noise of the past decade to find an interpretative framework.

The turn began with the US-manufactured sub-prime crisis, which led to severe banking problems across Europe, showing that when the US sneezes, Europe gets the cold. The Eurozone economy rapidly collapsed. The real Euro-specific drama came in April 2010, with the revelation by the then-Greek Prime Minister Papandreou, with a sunny Kastellorizo in the background, of the real magnitude of the Greek deficit. He argued it was due to “incomprehensible mistakes, omissions, and fatal decisions and the huge problems that the previous government has left behind”. With this theatrical opening, the Euro debt crisis unfolded, and spread across Europe. The book does an excellent job in highlighting the most relevant stages, although leaving out some important contributions in the existing literature.

Having set the stage, the book moves into the two contested concepts of legitimacy and populism. It also digs into the vast literature on populism and its interconnection with Euroscepticism. Then it enters into some shaky territory, with difficult questions such as at which point targeted criticism becomes Euroscepticism. Here, the narrative dwells with normative, theoretical and empirical dimensions, which may be deemed controversial by some. Nevertheless, the arguments brought forward are thought-provoking and engaging, and they are by and large convincing.

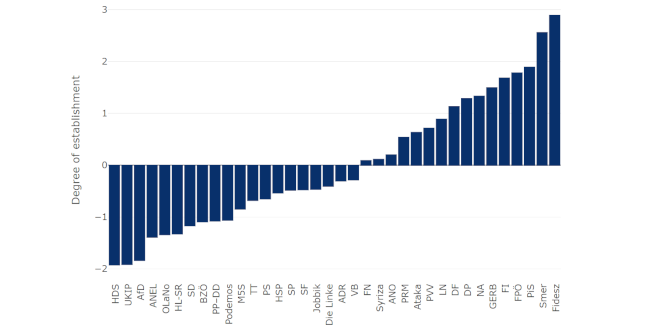

The book defines Eurosceptics as those political parties (and their supporters) against the allocation of national powers to the supranational (EU) level or against the content of European policies (e.g., migration, fiscal policies, or some of the exceptional ECB measures that became necessary during the crisis). Then it tries to distinguish between legitimate criticism of individual policies as a vital part of representative democracy, and criticism of the European Economic and Monetary Union as a policy. A substantial portion of the book is dedicated to the relation between crisis governance and changes in public opinion and support for the ECB. It identifies tensions between popular opinion and the policies carried out in the EU/Eurozone, and between the principles of democratic legitimacy and the way it has been challenged in the EU’s multi-level system of governance, particularly during the financial crisis.

ECB President Christine Lagarde and Philip R. Lane at an ‘ECB Listens’ event on 21 October 2020, Credit: Bernd Hartung/European Central Bank

Delors once said, “Not all Germans believe in God, but all believe in the Bundesbank”, a trust that certainly goes beyond the concept of legitimacy and legitimation. The book raises the issue of the need for widespread support of the central bank, especially at times of contrasting interests and conflicting positions among different countries.

One of the main conclusions is that adjustment programmes actively interfered with the principles of legitimation and accountability. “In the financial aid regimes, those parliamentary competencies have been altered substantively, as adjustment programmes decided externally by the IMF/ECB and European Commission-led Troika implied strong constraints for the national budgets and decisively limited the decision-making margin of national parliaments.” The book highlights the low degree of accountability and transparency of the crisis management tools activated with the European Stability Mechanism and the so-called Troika, consisting of representatives of the European Commission, the ECB, and the International Monetary Fund. It argues that the ESM regime of granting financial aid had a severe impact on representative democracy in the euro area countries. It concludes that “the budgetary decision-making power was handed over from the bodies that have been directly legitimised by the sovereign (national parliaments and governments) to bodies that either are only indirectly legitimised, such as the Eurogroup, international non-majoritarian bodies, such as the IMF, or third-party expert groups, such as the Troika”.

This criticism may go too far, given the nature of the intervention of any international organisation, and particularly the IMF, in helping countries to move out of a crisis and the generous financial effort put together by Eurozone countries to provide financial support to Greece. Still it has a point about the inter-governmental nature of the Eurozone and its parallel structure to assist countries, which bypass the democratically elected European parliament and allows countries to weigh in on decisions according to their capital keys in the ESM. As a result “the German Bundestag, deciding upon the conditions of austerity for Greece, also obtained a form of co-decision right on details of the Greek budget”. Again, this is not an oddity when looking at how assistance programmes are designed internationally, the legal setting of international organisations, and the balance of power between creditor and debtor states, but it appears as an aberration in a community that has set up democratic institutions and aims to become more than just a club of creditor states.

The ECB played a decisive role in these mechanisms, somewhat hampering national representative democracies and legitimacy, and “emerged as one of the most prominent executive forces”. The authors are harsh: “the central bank took on additional functions and interfered with representative democratic mechanisms without necessarily being sufficiently legitimised and accountable for doing so”. The authors conclude: “the central bank thus became an increasingly political actor, while a considerable number of non-monetary issues have been associated with the ECB’s policy output”. The substance of the argument may be different, especially taking into account the pragmatic attitude and the choice for executable solutions, but there is no doubt that there are some serious institutional design deficiencies and legitimacy deficits. It is partly the result of decisions undertaken under the pressure of a crisis and then included into separate treaties.

The book concludes that (1) “all brought a power shift from legislative to executive and expert forces”, and (2) “the new intergovernmental institutions were set to bypass the European Parliament”, (3) “having shifted certain parts of the decision-making competencies outside of the existing EU framework and away from most of the national representative institutions altogether represents a critical legitimation problem”, and (4) “the financial aid part of crisis governance severely impeded national representative democracies, especially in debtor states”. However, the alternative route would have been to bring everything inside the EU Treaty framework, which requires a much lengthier, complex and risky process. It would not have been compatible with a crisis-response mode. At some point, however, bringing everything under one roof must be the aim. The Convention on the Future of Europe, scheduled to close its works in the first half of 2022, should be the proper launch pad for that.

The European Parliament concluded: “Two-Pack and Six-Pack have gone to the limits of EU competence in the field of economic policy. Any further deepening of the Economic [and] Monetary Union might either require Treaty change or recourse to the intergovernmental method: both options would raise the issue of parliamentary control”. Yet, recently European institutions were able to pull out of their hat Next Generation EU, which again stretches the EU framework to the limits, and for good reasons. However, the institutional framework, including some issues of legitimacy for the ECB, remains unaddressed.

Another conclusion of the book is that the ECB cannot operate successfully when populist forces in its member states increasingly seek to assert their sovereignty and mobilise against the monetary union. Thus, the current approach to crisis management and overall governance needs to be changed. Encouragingly, it appears that European policymakers listened to these calls (although the book was not yet published at the time), with the massive anti-pandemic fiscal package and the unprecedented policy response by the ECB.

The authors updated the book before publication with an epilogue on “The 2020 Global Pandemic and Its Fallout for the ECB and the Euro Area”. They said that “this crisis not only underlines the necessity to include the current system of financial aid into the framework of the EU Treaties, but it also provides a strong rationale for radical new fiscal instruments to support the claims of member states most hit by the COVID-19 via what is frequently called Eurobonds”. “It is also, and perhaps most importantly, a matter of safeguarding democratic and political cohesion in a post-COVID-19 EU against growing populist and anti-democratic temptations.”

“In the end, something’s got to give, and governments may well be forced to pick their poison eventually: either to agree on a full-fledged Fiscal Union themselves, fed by transfers or mutualised debt, or to let the ECB overcome some or all of its remaining limits, including the prohibition of monetary finance. If not, the euro area is highly likely to emerge from the crisis much weaker than it had entered it—which would, yet again, make it an easy target for populist attacks.” Political leaders and the ECB seem to have finally got their acts together, and the policy response has so far been effective. However, the book calls for profound governance changes and answers “to the populist forces that are sure to reappear once the emergency is over”.

Sometimes, however, there is confusion in the book between the aim for independence and legitimacy on the one hand, and the need to establish a dialogue between the monetary and the fiscal side, while preserving monetary dominance. Both aims are entirely justified, in my view. This debate has never been as pressing as it is today, with many central banks having already reached the effective zero-lower bound on interest rates and having to rely on the fiscal side to achieve their mandated objective. It also brings back similar moments in history during which central banks took an essential role in driving countries out of war-related recessions. Even in that case, central banks had to interact with the fiscal side to achieve maximum results. The post-pandemic environment will likely be reminiscent of the post-war period, with the prevalence at that time of the objective of economic growth while maintaining stability.

The current situation forces policy coordination, but the risk is also that of fiscal dominance, with creeping loss in central banks’ independence and inflation-fighting credibility. In my view, there is a possible synthesis between independence and the necessary policy dialogue.

Some perceived the ECB to have overstepped its mandate with the introduction of the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT), and this contributed to the rise of populist anti-euro movements, and not just in Germany. On the other hand, the Greek crisis was a testament to the tensions between elected politicians and unelected bureaucrats and raised the issue of popular support. The point of Troika-like programmes is still very much alive today in the debate about the conditionality of the Next Generation EU, and the activation of ESM’s ECCL. The book expertly documents how we got to the point where we are today, and how far the debate has advanced.

When I once tried to explain the specificities of the policy setting in the European monetary union to a US investor, he reacted by saying “What a monster!” Indeed, the complexities and interactions of the European project sometimes are hard to grasp entirely even by insiders. Documenting the complicated itinerary of the European Central Bank in its search for legitimacy and popular support while respecting its mandate is indeed a novel approach and the most comprehensive so far. It is certainly an interesting read for those willing to better understand Europe’s complex policy setting. Although this latter is specific to the European Central Bank, some aspects are valid for all central banks around the world.

Perhaps, there should have been more effort to bring together the different parts of the book, which at times appear discordant and not properly integrated, or have more clearly separated the different contributions by the authors.

As pointed out by Paul De Grauwe in the foreword, the question of legitimacy and independence of central banks is relatively new (with a few exceptions). It was the reaction to the hyperinflation of the ‘70s, at least partly attributed to the interference of politicians in the conduct of monetary policy and the funding of government deficits. It then got a boost from the supranational status of the European Central Bank, possibly the most independent central bank in the world. In practice, it also put individual countries in a position to issue their debt in a foreign currency, which contributed to a self-fulfilling crisis and multiple equilibria.

Today’s crisis has thrown into sharp relief the difficulty for a central bank to operate in an environment of incomplete integration, fragmentation, and still evolving governance. It shows how much we have to learn from past experience and mistakes. It also illustrates that convictions and policy recipes that appeared written in stone are instead contingent on the state of the economy and the historical moment in which they form. It reminds us that economics is a social science and needs to be contextualised. New challenges require new ideas and policies, and the old ones have to be continuously tested in light of new developments. The book shows that the political economy of central banking is far from a crystallised subject.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Bernd Hartung/European Central Bank (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)