In Defeating the Dictators: How Democracy Can Prevail in the Age of the Strongman, Charles Dunst considers how democratic governments can address the challenge of the global rise of autocracies. Heeding the erosion of public trust and the danger of backsliding as far-right parties rise, Dunst illustrates why policymakers must do more to strengthen their democracies, writes Ahmet Furkan Ozyakar.

Defeating the Dictators: How Democracy Can Prevail in the Age of the Strongman. Charles Dunst. Hodder & Stoughton. 2023.

Undoubtedly, we are seeing the unprecedented ascendance of autocracies, both in the Global South and the Global North. Charles Dunst’s Defeating the Dictators: How Democracy Can Prevail in the Age of the Strongman presents a strategy for how governments can counter dictatorships comprising eight principles: merit (assigning the most competent people to the appropriate positions based on their ability instead of their connections); accepting accountability accountable for critical failures and decisions; earning public trust; long-term thinking (instead of restricting the plans for the duration of politicians’ elected terms), providing a safety net to prevent citizens’ economic suffering in times of turmoil); investing in human capital developing infrastructure; and fostering immigration to maintain the workforce and development of the country. By disregarding these principles in the policymaking process, Dunst argues, present-day democracies risk losing their fundamental principles such as the superiority of law, the existence of opposition and changing of the government by elections and may trigger the rise of far-right parties in democracies, exemplified in the case of Viktor Orbán in Hungary. Failing to invest in these eight principles can result in the backsliding, which leads to democracies’ constituents comparing their countries unfavourably against certain autocracies which appear to prosper and may eventually stimulate the rise of populists and autocrats at home.

Undoubtedly, we are seeing the unprecedented ascendance of autocracies, both in the Global South and the Global North. Charles Dunst’s Defeating the Dictators: How Democracy Can Prevail in the Age of the Strongman presents a strategy for how governments can counter dictatorships comprising eight principles: merit (assigning the most competent people to the appropriate positions based on their ability instead of their connections); accepting accountability accountable for critical failures and decisions; earning public trust; long-term thinking (instead of restricting the plans for the duration of politicians’ elected terms), providing a safety net to prevent citizens’ economic suffering in times of turmoil); investing in human capital developing infrastructure; and fostering immigration to maintain the workforce and development of the country. By disregarding these principles in the policymaking process, Dunst argues, present-day democracies risk losing their fundamental principles such as the superiority of law, the existence of opposition and changing of the government by elections and may trigger the rise of far-right parties in democracies, exemplified in the case of Viktor Orbán in Hungary. Failing to invest in these eight principles can result in the backsliding, which leads to democracies’ constituents comparing their countries unfavourably against certain autocracies which appear to prosper and may eventually stimulate the rise of populists and autocrats at home.

Democracies risk losing their fundamental principles such as the superiority of law, the existence of opposition and changing of the government by elections and may trigger the rise of far-right parties in democracies.

Singapore is exemplified as the only successful autocracy amongst all owing to how tightly the country is run since gaining independence, abiding by many of the principles Dunst outlines. The author argues, however, that Singapore could not maintain this good governance and underlines that it is still an authoritarian government which prevents the existence of political competition through a one-party system and limited civil freedoms. Therefore, Singapore cannot be an alternative to democracies, and it’s expected that Singapore’s capability declines too. Apart from Singapore, the book illustrates how China, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia are doing better than democratic countries in terms of infrastructure, public trust and safety nets.

[In] the US, UK, Japan, and South Korea, […] public trust towards governments is staggeringly low, undermining the claim that democracy is the most advanced form of government.

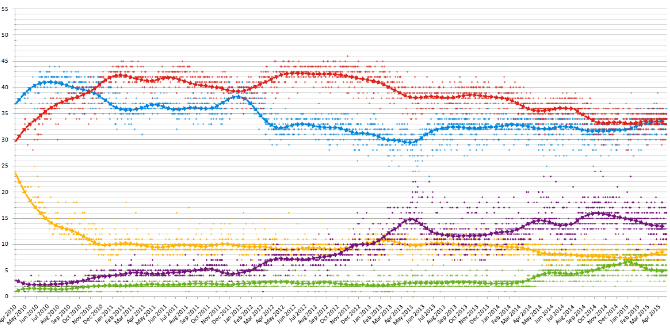

The book demonstrates how democracies grapple with difficulties, for example, the economic crises caused to implement illiberal practices in Brazil, Hungary and Poland or Trump’s encouragement for the attack on the US Capitol on 6th January 2021. As Dunst argues, these signs of weakened democracy boost the success stories of autocrats. Although democratic countries remain ahead in this “competition” for public trust, its decline is frightening. This book illustrates why we should feel concern about the future of democracy, focusing on the US, UK, Japan, and South Korea, where public trust towards governments is staggeringly low, undermining the claim that democracy is the most advanced form of government. The developments during and after the COVID-19 pandemic have increased public distrust. The delinquency of then-prime minister Boris Johnson and his “Party-gate” scandal evidenced the lack of accountability in one of the most advanced democracies and provided stark contrast to the success stories of certain authoritarian governments’ management of the pandemic, such as China.

Signs of weakened democracy boost the success stories of autocrats.

One of the features of democracies is to implement long-term thinking over short-term planning that courts the electorate. This requires a blueprint for a system that can cope with crises, underpinned by enough human capital. Dunst emphasises the lack of public infrastructure in democracies and underlines that this deficiency is not only eliminated with more buildings or more bridges, but also placing emphasis on digital infrastructure. Moreover, the importance of safety nets is also discussed in detail to evidence how democracies failed to shift the economic burden of the pandemic away from their ordinary citizens.

An inclusive immigration policy should occupy the agenda of Western democracies if they are prioritising the defeat of dictators abroad as well as at home.

Dunst selects human capital and immigration as two of his core principles for strengthening democracies, and these could in fact be merged. Drawing on their own human capital and immigrants can boost economic development and trust towards both autocratic and democratic governments. Many democracies are seeing ageing populations and need young and skilled foreigners to supplement the workforce. Dunst presents the story of the founders of Google, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, to show how immigrants bring innovation to a country. On the other side, he argues how autocratic countries can stifle both immigration and native human capital, giving the example of the founder of the tech conglomerate Alibaba, Jack Ma, who faced restrictions in China when he drummed up business. While Dunst argues that the immigration policies of democracies need to be reformed, he does not criticise discriminatory immigration policies, such as the US ban on some Muslim-majority countries. The racist immigration policies of the Western world have become more apparent following the Russian invasion of Ukraine when similar immigration policies and regulations was not streamlined for the Syrians who were fleeing a brutal dictator, Bashar al-Assad; Afghans following the collapse of their government and the Taliban seizing control, and more recently, those feeling the conflict in Sudan. In short, an inclusive immigration policy should occupy the agenda of Western democracies if they are prioritising the defeat of dictators abroad as well as at home.

The author […] bypasses acts of aggression perpetrated in Western democracies, such as the US’s invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan

The author also discusses Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China’s crimes against Uyghurs in Xinjiang and Saudi Arabia’s bombing of Yemen, however, he bypasses acts of aggression perpetrated in Western democracies, such as the US’s invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan. This selective argumentation compromises the general framework and may make the reader think that invasions are characteristic of autocracies only.

Another controversial aspect of the book is that, while Dunst underlines the necessity of defeating autocracies, he also encourages democracies not to cut off relations with them. Although this argument has its own rationale, such as benefiting from technological exports from autocracies such as China, one could ask whether these autocracies may feel more justified in their oppressive actions when they retain steady economic relations with democracies.

While Dunst praises some aspects of dictators and provides a framework for defeating them, he does not examine countries such as North Korea, Iran and Syria whose dictators also pose challenges for democracies. The omission of these countries is glaring, perhaps suggesting that Dunst does not believe their defeat Is possible through the principles he lays out.

Overall, this book sheds light on the odds for survival for democratic governments if necessary measures are not taken at home. Defeating the Dictators argues that if the ultimate purpose of democracies is to defeat dictators, the aforementioned eight principles must be prioritised to overcome the stagnation and inadequacies of democracies as they stand. From this viewpoint, this book is an important reference guide, not only for the policymakers and researchers but also for the non-specialist readers who are worried about the rise of autocracies, demonstrating how they would also contribute this revitalisation before it is too late.

Note: This review first appeared at our sister site, LSE Review of Books. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: FrankHH/Shutterstock.com