EU courts handle cases of considerable importance for European citizens and policymakers, yet we know little about the ideology of EU judges and how it might influence their decisions. Drawing on a new study, Wessel Wijtvliet and Arthur Dyevre demonstrate that the median ideological position of a judicial panel is a significant predictor of rulings on competition and state aid cases.

The appointment of Amy Coney Barrett to the United States Supreme Court shortly before the US presidential election brought a flurry of comments about her ideological leanings and the impact she might have on the position of the Court during a Biden presidency. Yet neither that, nor the partisan wrangling that accompanies judicial appointments, is particularly unusual in the United States, where US Supreme Court justices attract considerable media attention and the influence of ideology is both well documented by a vast body of academic research and fully acknowledged by court watchers.

In comparison to US federal judges, European Union courts labour in relative obscurity. Whether it is about the integration process and the supremacy of EU law, privacy and data protection or anti-competitive practices, EU courts handle cases of considerable significance for Europeans and EU policymakers, easily putting them among the world’s mightiest judiciaries. Yet little is known about the ideology of EU judges and how it might influence the direction of their rulings.

Academic research into the influence of ideology has been hampered by the institutional setup of EU courts, which precludes the disclosure of individual votes and opinions. The secrecy surrounding the internal deliberation process means that most of the techniques employed to investigate judicial ideology in the American context are inapplicable to EU courts. Scholars have thus been left with crude proxies such as the partisan affiliation of the appointing government or the legal tradition of the appointed magistrate to try and track ideological variations and link those to case outcomes.

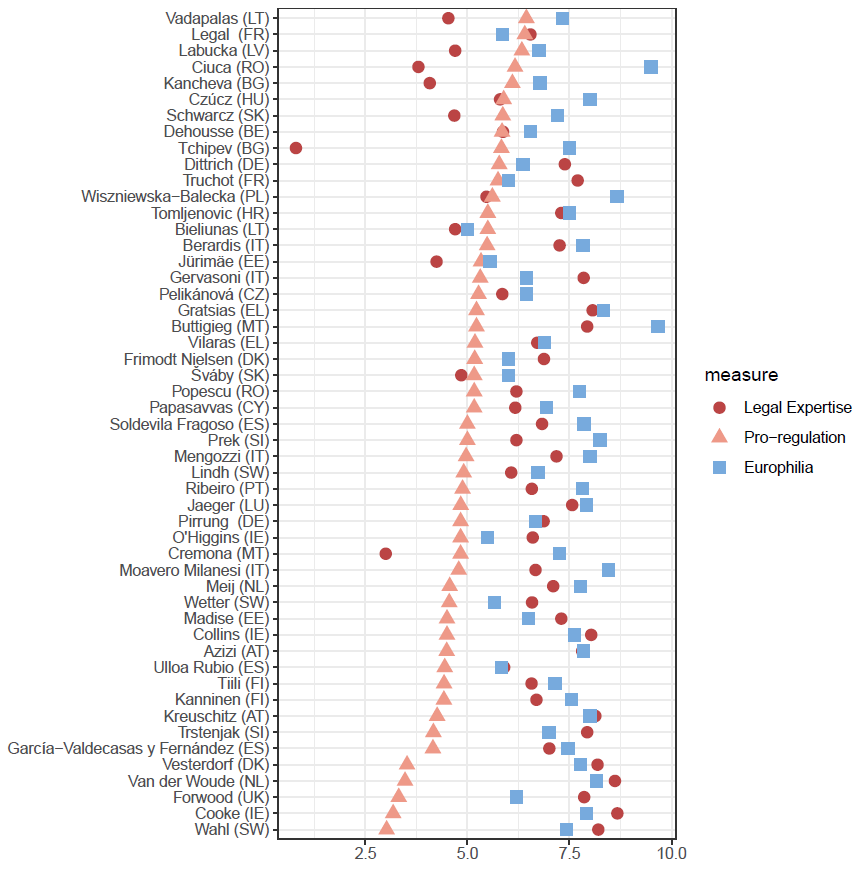

In a recent study, we seek to shed new light on the effect of ideology on EU courts by using an alternative measure of judicial ideology. We asked 46 legal experts to rate 51 judges of the General Court of the European Union on three dimensions: (1) attitude towards market regulation, (2) attitude towards European integration and (3) legal expertise. We then took the average of these ratings to compute the judicial scores displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Judicial scores of General Court judges generated from expert ratings

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in European Union Politics.

Consistent with prevailing perceptions in legal circles, former civil servants (such as French judge Legal or German judge Dittrich) score high whereas judges with a background in private legal practice (including Dutch judge Van der Woude and British judge Forwood) score low on the pro-regulation dimension. Scores on this dimension are also correlated with attributes of the appointing member states, such as perceived ease of doing business and membership of the former Socialist bloc, which suggests systematic cross-national disparities in appointment dynamics.

Drawing on these judicial scores, our study found robust evidence that, in competition and state aid cases, panels with a more pro-regulation median judge favoured the European Commission over private litigants. Whereas EU studies imply that attitudes towards integration should define the dominant ideological cleavage on EU courts, we found less robust evidence for the influence of Europhilia.

To be sure, ideology cannot explain all variations in judicial outcomes. Yet its effect is far from negligible. A one-unit increase in the pro-regulation score of the panel median reduces the probability that the panel will rule against the European Commission by 10 to 19 per cent. The effect of Europhilia is somewhat smaller and varies between 4 and 7 per cent, depending on econometric specifications.

While our empirical findings challenge the premise of much of the EU judicial politics literature that Europhilia forms the primary dimension of contestation among EU judges, they are consistent with research on US federal courts, which has shown that variations in attitudes towards private business define the central ideological cleavage in economic cases.

Our empirical analysis does not rule out the possibility that the weight of ideological motives might differ in other areas of EU law, notably where disputes pertain to the interpretation of competence provisions and the allocation of powers between EU institutions and national governments. Yet our study shows how our measurement strategy might help future researchers to surmount the practical hurdles stemming from the opacity of the internal deliberation process. Slowly but surely, social science will pierce the veil of secrecy of EU courts.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in European Union Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Court of Justice of the European Union