Issues surrounding Muslims have become a prominent feature of French politics. Drawing on a new study, Steven M. Van Hauwaert and Manlio Cinalli present a novel measure of how views toward Muslims have changed within France, and how government policies have responded to these shifts in public opinion.

Issues related to Muslims play an important role in today’s politics, especially in France, where Republican values and secularism are foundational principles. Much of the scholarly discussion of the topic relates to Muslim migration and integration in its narrowest sense. While such studies undoubtedly have value, other aspects of the study of Muslims remain underexplored. In a recent study, we take a more overarching approach and relate contentious politics surrounding Muslims in France to various components of the public and policy spheres.

The public’s views toward Muslims

There has always been an extensive and visible presence of Muslim migrants in France. Combined with the secular nature of French Republicanism, this has given rise to contentious politics surrounding Muslims. But to understand this phenomenon, it is important to grasp what French citizens really think and want in relation to this issue.

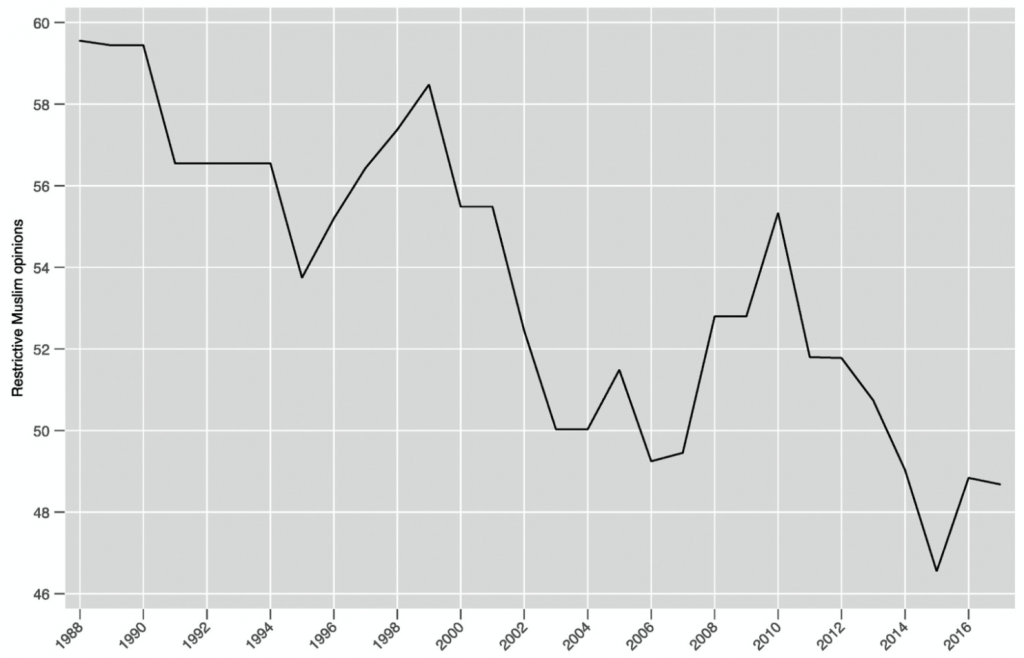

We use unique data from the Global Public Opinions Project and rely on a dyadic ratios algorithm to construct the first ever aggregate-level measure of how citizens feel about Muslims. This measure, which we label ‘Muslim opinions’, is shown in Figure 1 below. The measure ranges from support (low values) to opposition (high values) vis-à-vis Muslims.

Figure 1: Views toward Muslims in France (1988-2017)

Note: A higher value in the figure indicates citizens in France have a more restrictive view toward Muslims, with a lower value indicating citizens have a more supportive opinion. For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study.

The figure illustrates a long-term near-linear decline in restrictive opinions toward Muslims amongst French citizens. This might be surprising considering recent scholarship suggests European politics has been undergoing a right-wing shift (a so called droitisation), particularly in relation to migration issues. Yet, there is little to no evidence of this in our research, at least not amongst French citizens vis-à-vis Muslims.

In fact, we observe the opposite trajectory in France: opinions toward Muslims have moved in tandem with some of the broader social progression and emancipation processes that identify many contemporary liberal democracies. We do notice some signs of cyclicality, as well as two noteworthy episodes where opinions became more restrictive, namely in the mid- to late 1990s and the mid- to late 2000s. The latter relates to a series of Islamic terrorist events and the 2005 French riots, respectively. Neither of these shocks, however, appear to have had a lasting effect.

Muslim-related policies

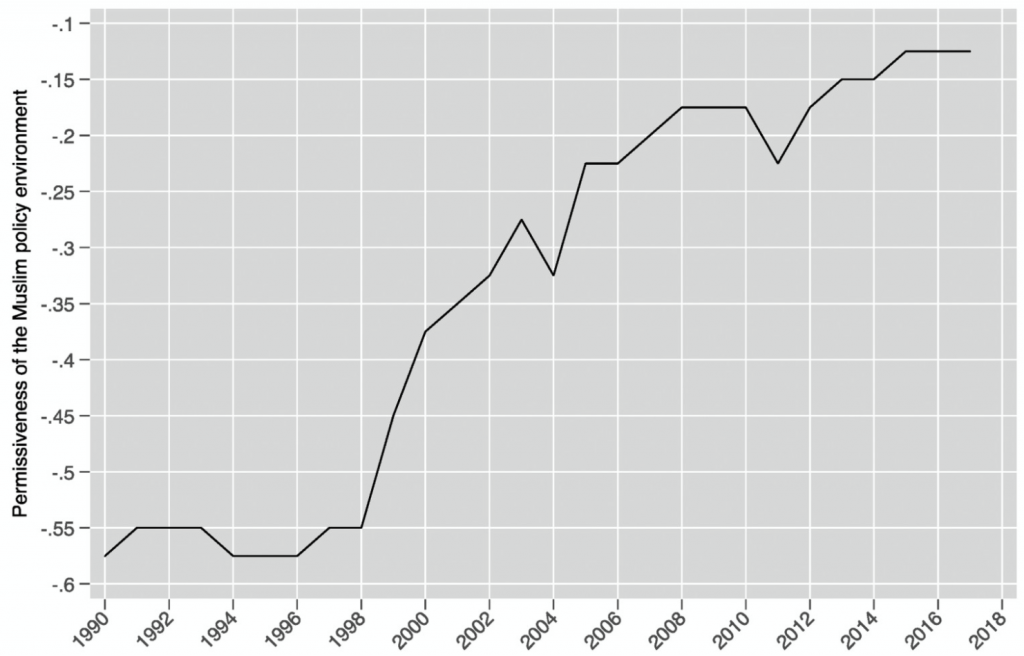

Two intertwined components of the political sphere reflect the above-mentioned political demands, namely claims by political parties, i.e. how parties change, and policymaking. Here, we focus on the latter and use our own data to provide insights into the actual policy environment surrounding Muslim-related policies. We collected a unique series of 19 Muslim-related policy indicators that cover the period from 1990 to 2017. For each year, we then construct an average index across those indicators that ranges from -1 (most restrictive) to +1 (most permissive). Figure 2 presents the evolution of the aggregated policy indicators’ annual averages.

Figure 2: Muslim-related policies in France (1990-2017)

Note: A higher value in the figure indicates policies in France have become more permissive toward Muslims, with a lower value indicating policies have become more restrictive. For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study.

Two interesting observations stand out. First, the initial period covering the 1990s and the 2000s saw Muslims become more visible in the policy sphere, with governments increasingly recognising Muslims. While the policy measure reaches a more neutral position (close to zero) from the mid-2010s onwards, the fact it remains below zero highlights that policies in France continue to be somewhat selective in the opportunities they provide for Muslims.

Second, the aggregate policy measure nearly systematically (and linearly) becomes more permissive over time. This movement towards a more ‘open’ policy sphere is particularly prevalent since the mid-1990s. Altogether, however, this does not mean that contentiousness has decreased. Rather, it suggests that a fairly restrictive policy sphere in the period between the 1980s and the 1990s has systematically evolved into a less restrictive one.

Congruence across the policy and public spheres

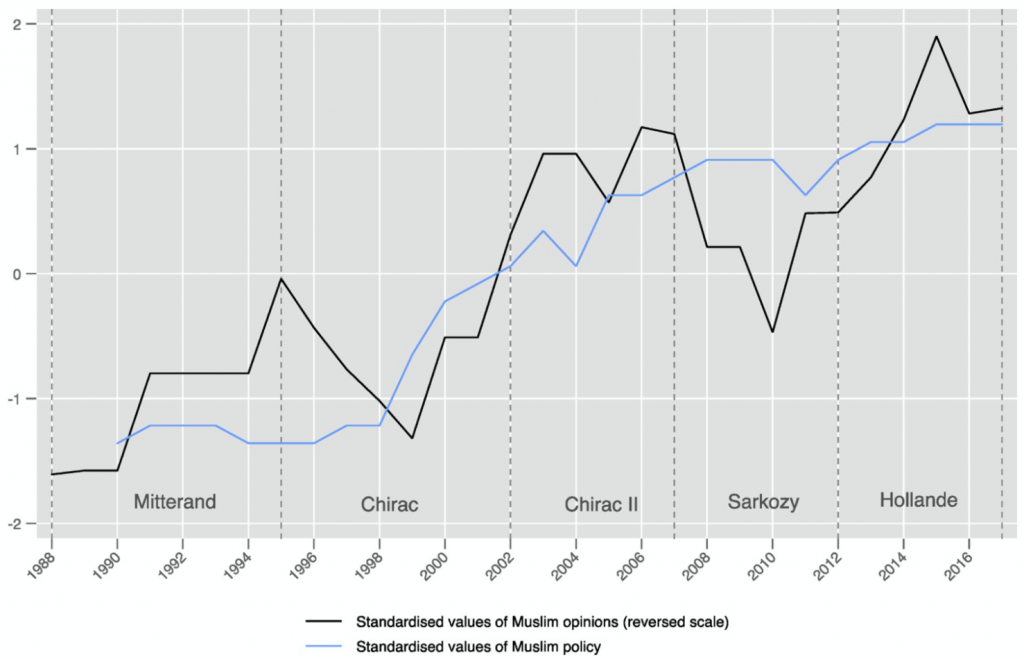

Having considered the salience of Muslim-related issues, we therefore expect ideological congruence between citizens and government preferences in this domain. To provide a more detailed analysis of this, we overlap the previous opinion and policy figures.

For comparative purposes, we standardise both variables. Additionally, we reverse the scale of Muslim opinions so that higher values indicate more support for Muslims. Figure 3 illustrates a dialogue of sorts between the movement towards a less restrictive policy sphere and less restrictive opinions in the public sphere (pairwise correlation = 0.84). This leads us to believe that, concerning the contentious politics surrounding Muslims in France, what citizens want is also reflected in what governments do (and vice versa).

Figure 3: Views toward Muslims and policies toward Muslims in France (1988-2017)

Note: A higher value in the figure indicates citizens in France have a more supportive view toward Muslims and that policies toward Muslims are more permissive, with a lower value indicating the opposite. The vertical lines indicate presidential elections in France. The names highlight presidents. Until 2002, the standard term in France was seven years. After 2002, it became five years. For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study.

While we do not find perfect congruence, there is some indication that an increase in anti-Muslim opinions might be favourable for right-wing presidential candidates (Chirac I and Sarkozy). As a whole, we find important indications of congruence between what citizens want and what governments give them. That is, policy and opinion measures suggest that citizens’ political inputs and governments’ outputs move together through time. This is exactly what we would expect in a salient domain and for a politicised issue such as the politics surrounding Muslims. Naturally, congruence across public and policy spheres is not perfect, as there remains a certain degree of imbalance between policy and public opinion.

What is important to highlight here is that a limited degree of incongruence is not necessarily problematic, for two important reasons. First, there are other actors (e.g. parties and interest groups) that have a policy impact. While most democratic systems pursue high levels of congruence, none achieve this flawlessly for the simple reason that interests across issues are often conflicting and policy may operate at a much slower pace than the formation of public opinion. Second, limited levels of incongruence are not necessarily problematic from a normative perspective. Only structural incongruence can be problematic for the implementation of democratic principles and overall democratic functioning. This is not the case here.

Altogether, our findings suggest French democracy is relatively effective, at least regarding issues related to Muslims. While this finding is in line with theoretical expectations from the macro polity literature, it is nonetheless a surprising observation in France specifically. That is to say, considering the Republican and secular framework that underpins societal and political developments in France, we would expect this to restrict the political and societal translation of any phenomenon that challenges it. Yet, under these circumstances, we nonetheless find high levels of congruence in a relatively unfavourable setting. This renders us hopeful about democratic representation and the normative functioning of democracy, even in a contentious field and a relatively disadvantageous context.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study in Ethnic and Racial Studies

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Shutterstock