The tendency for citizens to ‘rally round the flag’ during a crisis led many observers to assume the Covid-19 outbreak would be a negative development for the electoral fortunes of populist parties. Yet as Brett Meyer explains, this pattern has been far from uniform across western Europe. Drawing on a new study, he highlights several structural changes brought on by the pandemic which may ultimately play to the strengths of populist politicians.

It has become clear that Covid-19 hasn’t been the severe blow to populism that some commentators had predicted. And this is in part because, contrary to the experience with Donald Trump in the United States, most populist leaders around the world took Covid-19 seriously. But populist leaders who took Covid-19 seriously still varied in how they took it seriously, with several using it as an opportunity to further their illiberal projects by implementing excessive emergency powers and cracking down on the opposition.

In a new study, I have examined the responses of populist opposition parties to Covid-19 in nine western European countries and their governments’ efforts to fight it. This is not the first multi-country piece on populist responses to Covid-19 in western Europe – previous work has shown that most populists in Europe have taken Covid-19 seriously and have used it to push themes for which they had been arguing before the pandemic, especially the need for stricter border controls.

However, I wanted to investigate further the differences in responses across populist parties to their governments’ actions. While some populist politicians like Geert Wilders and Marine Le Pen made a splash in the early weeks of Covid-19 for their attacks on their governments, we heard much less about populist responses in the Nordic countries and Germany. I also wanted to understand how the economic fallout from Covid-19 might affect support for right-wing populist parties in the future. I engaged with recent work on structural changes in labour markets and how employment affects voting preferences to achieve this.

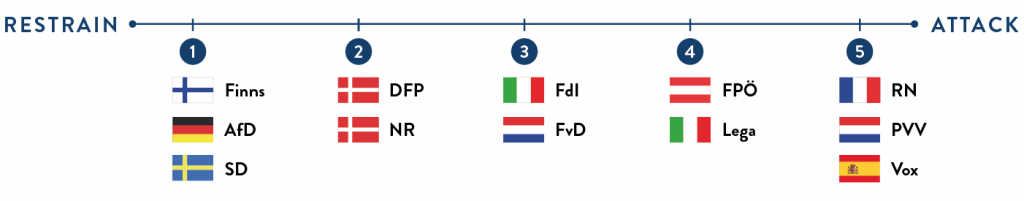

I divided the examination of western European populists’ responses to Covid-19 and their governments’ actions into two periods: the first few weeks of the pandemic; and the rest of the summer of 2020. While all parties that I examined appeared to take the virus seriously in the early weeks of the pandemic, I found substantial variation in their responses to their governments’ actions. These ranged from immediately attacking their governments for not closing the borders and enacting stricter lockdowns to supporting their governments’ policies and admonishing party members who criticised them. I developed a five-point scale of the degree to which these parties attacked their governments in the early weeks of Covid-19, which is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: ‘Restrain-attack’ scale of cultural populist response to governments during the early weeks of the Covid-19 pandemic

Note: Abbreviations are as follows: Finns – Finns Party; AfD – Alternative for Germany; SD – Sweden Democrats; DFP – Danish People’s Party; NR – New Right; FdI – Brothers of Italy; FvD – Forum for Democracy; FPÖ – Freedom Party; Lega – League; RN – National Rally; PVV – Party for Freedom; Vox – Vox.

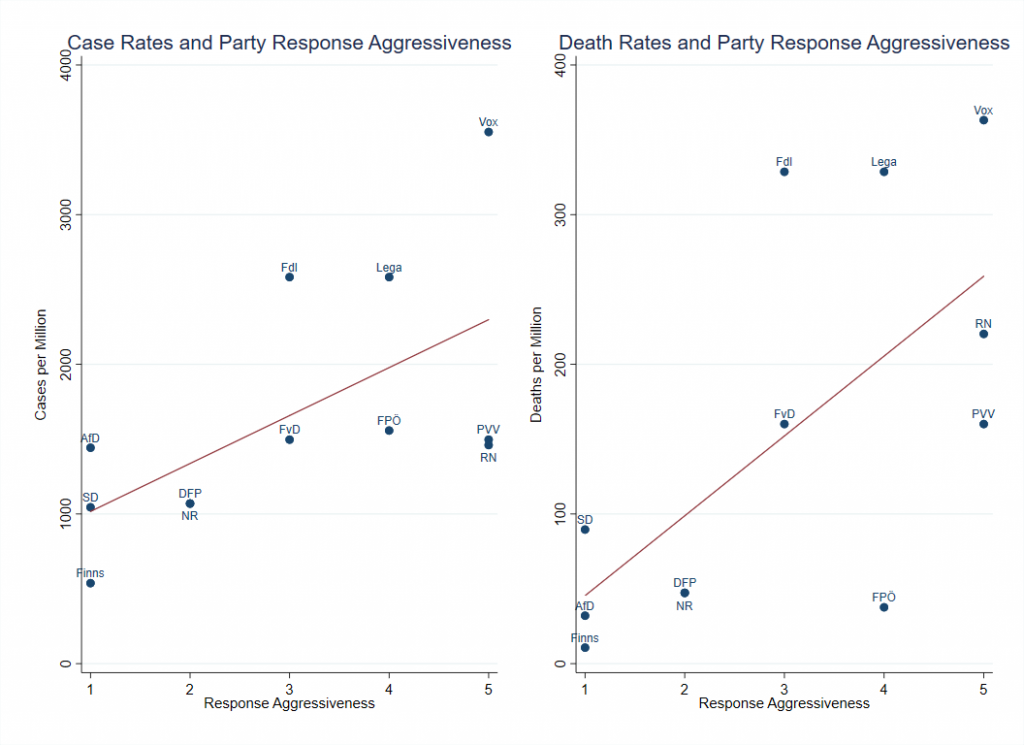

Notice that some of the countries in which populists attacked their governments, like Italy and Spain, were among those that had the worst outbreaks in the initial weeks of the pandemic while many of the parties which refrained from attacking their governments were in the Nordic countries and Germany, where cases and deaths in the initial weeks were low. I investigated the relationship between case/death rates after roughly one month under the pandemic and parties’ responses to their governments. The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Case/death rates and party response aggressiveness

Note: Cases per million and deaths per million are calculated by the author using population figures from the end of 2019.

Figure 2 indicates a positive relationship between case/death rates and party aggressiveness during the first few weeks of the pandemic. But the interpretation of this relationship is not straightforward. On the one hand, we might expect parties to be more likely to attack their governments when the problem is worse because this signifies a policy failure. In the early weeks of Covid-19 however, knowledge about the virus was poor and ideas for how to respond were limited to near-total lockdowns. On the other hand, the public tends to ‘rally around the flag’ to support their leaders in times of crisis and it might be expected that attacking the government during the height of a pandemic would cost parties support.

Rather than being a response to their governments’ Covid-19 policies, it is likely these responses say more about these parties’ future political aspirations. Parties which restrained themselves, like the Finns and the Sweden Democrats, have been trying to demonstrate to mainstream right parties that they can be suitable partners in future coalition governments. This concern is less relevant for aspiring country leaders like Marine Le Pen or Matteo Salvini of the Italian Lega, a party which has already been in governing coalitions like the Austrian FPÖ, or a party like the PVV, which has basically ruled out participation in government.

While several parties restrained from attacking their governments during the early weeks of the pandemic, they became more critical into the summer. All parties coalesced around three main criticisms of their governments: that government policymaking was neither inclusive nor transparent; that restrictions on personal freedoms were excessive; and that governments weren’t doing enough to support small businesses that had been most adversely affected by lockdowns. Several parties also criticised their governments for not focusing more attention on controlling the spread of Covid-19 in nursing homes.

Covid-19 and support for populist parties

This leaves the question of how the economic fallout from Covid-19 might affect support for populist parties in western Europe moving forward. Historical research has shown that right-wing populists benefit in the wake of financial crises, although so far Covid-19 has only induced a standard recession, not a financial one.

But Covid-19 has sped-up structural changes to the economy that potentially have major implications for right-wing populist support. Brick-and-mortal retail and small businesses have been losing ground to online shopping platforms like Amazon for years. Covid-19 has been a large positive shock in this respect, increasing the online purchase of consumer goods and groceries across the US and Europe.

While many blue collar workers in the US have done well during the pandemic, with a large increase in employment/wages in order fulfilment and construction jobs, the fallout will likely be heavy on small business owners. They are already disproportionately likely to support right-wing populists in Europe and populists may be able to increase their support among this group.

Perhaps of even greater long-run consequence, improvements in remote work platforms and other business software are allowing for the replacement of knowledge economy workers with “telemigrants” and “white-collar robots.” According to economist Richard Baldwin, up to 80% of these jobs could be susceptible. This would be a massive shock for workers in this sector, who have benefitted from past structural transformations.

It could be a blow not just to their wages, but to their social status. And recent work shows that the loss of social status related to employment or even just the perception that you might lose your social status, rather than economic hardship per se, increases support for right-wing populists. While knowledge economy workers are currently among the least likely groups to support right-wing populists, an implication of these findings is that this may not always be the case.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.