The Swiss town of Moutier has voted to leave the canton of Bern and join the neighbouring canton of Jura. Sean Mueller explains the complex history surrounding the decision.

On 28 March, a majority of 55% of voters in the Swiss town of Moutier decided to leave the canton of Bern behind and join the canton of Jura. You are forgiven for thinking we have all been here before, for we have – almost four years ago.

A slightly smaller majority of voters reached the same conclusion in the summer of 2017, but that result was later cancelled because too many irregularities had taken place before and during the vote. The voting booth is no stranger in this corner of the world, but more so than elsewhere in Switzerland, Moutier is connected to some peculiarly heated issues.

History, identity and canton-building

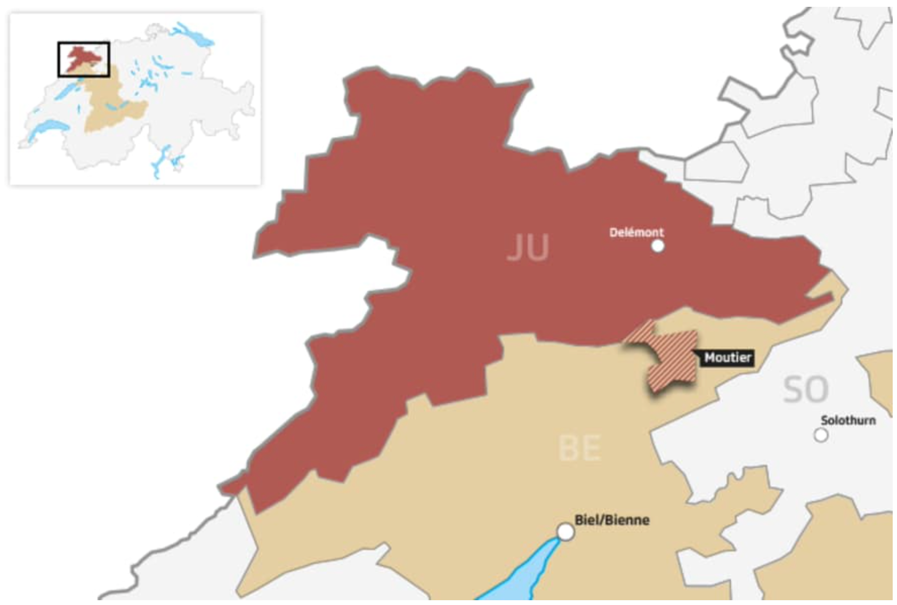

First, some context. The choice facing voters on 28 March was between Jura, with its 74,000 inhabitants, and Bern, with over a million (Figure 1). But why do voters have strong feelings about the cantons they are part of in the first place?

The 26 Swiss cantons are the historical, legal, political and social foundation of the Swiss federation. Most of them were there long before contemporary Switzerland was created in 1848. Still today, they levy all direct taxes, manage education and universities, run hospitals and car registrations, and have their own police force, courts and prisons.

Figure 1: Moutier and the cantons of Jura and Bern

Source: Swissinfo

Even nominally national policies such as military drafting, social benefits, the issuing of passports and naturalisation are managed with more or less cantonal autonomy. So, to be a canton is essentially the same as having the right to vote, since even at national level when it comes to constitutional questions all cantons – no matter their size – count the same.

Moutier and the ‘Jurassic question’

The referendum on 28 March was the latest development in a never-ending saga within Swiss politics known as the ‘Jurassic question’. Indeed, there have been no fewer than seven referendums in the last 50 years that concerned whether Moutier should be located in Bern or Jura.

The history that underpins this issue is complex and goes back to a decision made at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to assign a predominantly French-speaking area in the Jura mountains to the canton of Bern, where a majority of the population speaks German. This area subsequently became known as the ‘Bernese Jura’.

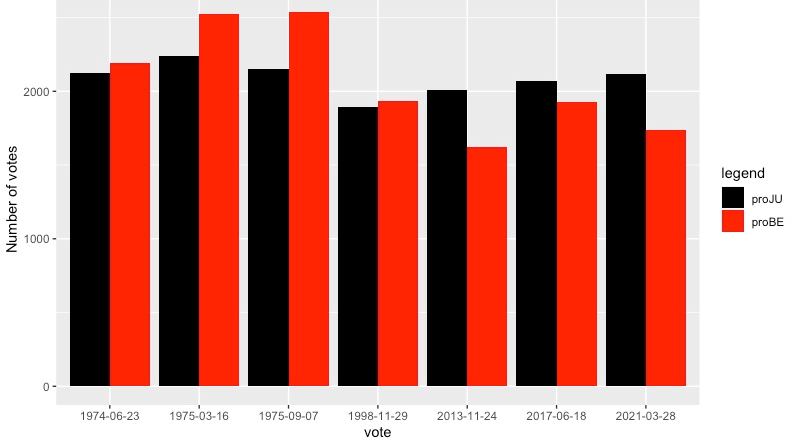

Responding to demands for secession from within the Bernese Jura, three referendums were held in the 1970s on whether a new canton should be created and what its precise territorial contours should be. This process ultimately led to the establishment of the canton of Jura, which was officially founded in 1979. However, only three of the seven historical districts in the area voted to join Jura, with the rest preferring to remain part of Bern – though one of these districts, Laufen, later left Bern to join the canton of Basel-Landschaft. In the 1970s, a majority of voters in Moutier opted not to embark on the new canton building project. An even smaller majority came to the same decision in a vote in 1998 (Figure 2).

Yet another referendum in 2013 revisited the issue, offering a second chance to the three districts that had remained with Bern to change their mind and establish a larger canton of a ‘united’ Jura. Once again, a majority of voters in all three districts opted to remain within Bern – but this time in Moutier, the result was different, with a majority backing the plan. The two votes that have been held since have confirmed this decision, with the ‘yes’ camp even gaining a few more adherents. Figure 2 shows how the size of the ‘pro-Jura’ and ‘pro-Bern’ camps has changed in the seven referendums held since 1974.

Figure 2: Size of the ‘pro-Jura’ and ‘pro-Bern’ camps in Moutier (1974-2021)

Note: The black bars indicate the number of voters that preferred to join the canton of Jura while the red bars indicate the number that preferred to stay in the canton of Bern. Data from the State Chancellery of Bern and the city of Moutier.

What explains this change of events? Lacking detailed survey data, we are forced to turn to aggregate results. In a previous study, I (along with my co-authors David Siroky and Michael Hechter) traced the cultural roots of the 2013 results at local level.

We concluded that preferences reflect culture, structural factors and the rational choices of voters. Culture explains the origins of political preferences through distinct cultural legacies. Structural factors constrain the effects of political preferences on collective action and decision-making. And rational choices can explain what people choose on the basis of those preferences.

Some eight years later, this explanation still holds. The dominant source of cultural legacies that we identified is Catholicism (and the French language) which confers “distinct political preferences for more statism”. Statism, or state interventionism in the economy and society, is better realised in Jura (which is 64% Catholic) than in Bern (which is 48% Protestant).

But even if preferences are fixed within groups, the groups themselves can change in size and relevance. And that is (probably) the second element of the explanation for why Moutier voted to join Jura, despite opting to stay in Bern in the 1970s. As Figure 3 shows, the main group in favour of staying within Bern, French-speaking Protestants, has declined in absolute size, while the main secessionist group, French-speaking Catholics, has grown.

Figure 3: Size of the four main cultural groups in Moutier (1970-2000)

Note: The figure shows the size of four main cultural groups within Moutier (Swiss citizens aged 18 and above). Swiss women only obtained the right to vote in federal (and Bernese cantonal and local) matters in 1971. Source: Census data as cited in Siroky, Mueller and Hechter (2015).

Lessons learned?

Only time will tell whether this was really the last piece of the Jurassic puzzle, the final vote to end them all. After all, we thought the same about the referendum in 2017, only to then be told by the (Bernese) courts that too many suspicious events had taken place.

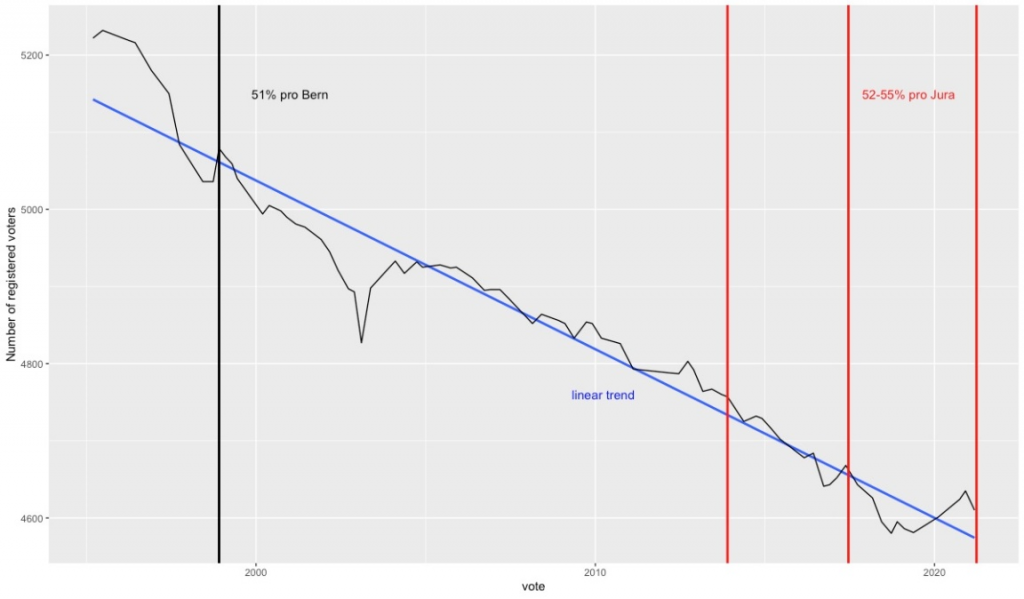

Back then, though no crime had actually been proven, given the tight margin of just 137 votes in favour of secession, cancellation and repetition seemed a prudent decision. Across Switzerland, local governments such as Moutier are in charge of the electoral registry and there was simply no way to tell whether an increase in the number of registered voters prior to summer 2017 was legitimate or not. Figure 4 illustrates how the size of the electorate has changed in Moutier since the mid-1990s.

Figure 4: Size of the electorate in Moutier for federal matters (1995-2021)

Note: The figure shows the evolution of the electorate in Moutier with a blue linear trendline and vertical lines indicating the last four referendums. Source: R-package swissDD from Politan

This time around, probably also because of Covid-19, the electoral campaign was less aggressive, the officials more muted, and voting was made more secure. In short, even in a country that votes almost daily, and even in a region accustomed to deciding its territorial belonging via referendums, improvements were made. It speaks to the goodwill of all those involved that such learning actually took place. And if that was still not enough, there is always the potential to hold another vote.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Hadi (CC0 1.0)

An interesting piece, thank you. I must confess this issue is new to me, but as a hereditary freeman of Berwick-upon-Tweed (an ancestor was mayor of the town in the 1790s) a very similar issue may well soon become fully active there. Berwick is on the North bank of the river Tweed, and is unquestionably geographically in Scotland. It was taken by the English over 700 years ago and changed hands another twelve times. After a long period of independence from both countries, over the pat century or so it has been increasingly absorbed into Northumberland, and is now a full part of England. An informal referendum there a few years ago indicated that a majority would prefer to be in Scotland. Those in Berwick certainly look with some envy on the greater financial support given to the neighbouring costal fishing towns up in Scotland.