Countries in Latin America and Europe, despite their substantial differences, are currently wrestling with a similar strategic question: whether they should engage in regional integration or ‘go it alone’. Carlos Cruz Infante and Roland Benedikter present a detailed comparison of Latin America and the EU across six key indexes. Their findings suggest there remain substantial advantages to pursuing regional integration – and the proposed Mercosur-EU agreement may pave the way to a closer alignment between the two areas.

Covid-19 has had a significant impact on every aspect of life in Latin America, much as it has in Europe. In general, the less wealthy a country is, the worse the situation has been. The World Bank estimated in 2020 that extreme poverty would grow significantly across the world for the first time in twenty years as a result of the pandemic. It is expected that Latin America will contribute substantially to this trend, while the European Union will be less affected.

In many Latin American countries, with their notorious systemic dysfunctionalities, Covid-19 has put institutional frameworks under strain. The pandemic has tested the capacity of states to cope effectively with social unrest and health emergencies, while also raising doubts about the ability of democratic systems to deal in symbolic and political terms with the crisis.

The rise of ‘vaccine nationalism’ has also cast doubt over the benefits of regional integration. While it is widely acknowledged that distributing vaccines through transnational cooperation is the most effective way for a highly interconnected world to overcome the pandemic, many countries in Latin America have continued along the distinctly nationalist path they have been on since 2019.

In the EU, in contrast, member states have managed to stick together, ordering vaccines jointly and maintaining a high degree of coordination, against the odds. Yet comparisons with the UK, which left the European Union at the beginning of 2020, have become unavoidable. Although Britain’s exit from the EU has had a negative impact on trade, the country’s new political independence has been viewed as a major advantage during its vaccination campaign. The UK managed to approve and acquire Covid-19 vaccines more rapidly than its former European partners, leading to a substantially quicker vaccination rate.

This situation has been watched closely in Latin America. A similar debate is playing out between the supporters of regional integration and those who prefer a global order made up of sovereign nations that, inspired by Donald Trump and Boris Johnson, put their own interests ‘first’. The EU’s errors and the extent to which UK politicians have been able to cite their vaccine rollout as proof of the merits of Brexit have been bad news for the supporters of regional integration in Latin America.

However, while international cooperation may slow down some initiatives in the short-term, there remain potential long-term benefits from pursuing closer cooperation. The OECD, for instance, has identified three advantages that are important in the current context. These are the extent to which cooperation can promote development processes through best-practice comparisons; the effect of cooperation on knowledge exchange and mutual learning; and the fact that cooperation creates new capacities to adapt to national and global reforms.

All of this raises the question of whether the EU’s regional integration approach remains a model for Latin America to follow or whether, like the UK, these states may be better off going it alone. This question is particularly relevant given the EU and Mercosur signed a trade agreement in 2019, following 20 years of negotiations, which, if ratified, promises to tie the two geopolitical areas closer together.

What does the data say?

To answer this question, we present a comparison between 17 Latin American countries and the EU’s 27 member states. While many states in Latin America envisage pursuing regional integration according to the EU model, this process remains at an early stage. As such, this comparison gives an indication of the potential benefits that may be acquired from following the EU model.

We use six well-known indexes covering democracy, the ease of doing business, freedom, corruption, happiness, and global health security. It is essential to note that this exercise is not an evaluation of development patterns between Latin America and the EU. Instead, the aim is to assess how regional cooperation has homogenised quality of life standards across the EU.

As will be seen, one of the most striking elements of this comparison is the extent to which countries in Latin America, despite having a better shared and unifying cultural and linguistic matrix than Europe, exhibit significantly more variation in terms of progress and well-being than the EU’s member states. This underlines that while collective action may be slower than the actions pursued by a single state like the UK, the EU’s members have a more evenly distributed level of well-being than other regions where international or regional cooperation is not as advanced.

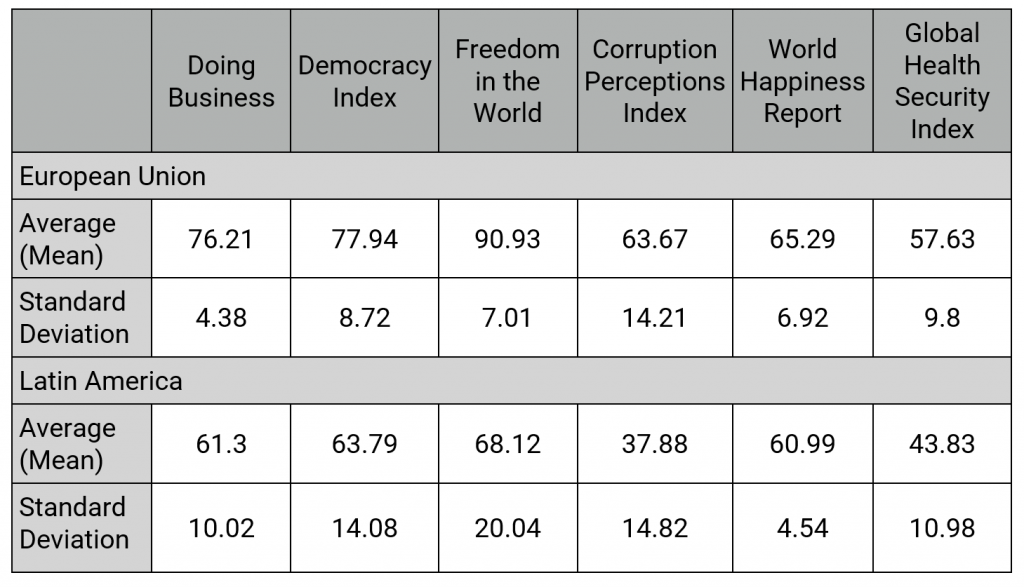

The table below shows the average scores for both the EU and the selected Latin American countries across the six indexes. As expected, the EU receives better average scores than the latter – and one reason could be that it has a more advanced level of alignment between its members. In the same table, we indicate each region’s standard deviation from the average. This deviation rate allows us to understand how homogeneous or disperse the data is among societies in the same area.

Table: Distribution of index scores in the EU and Latin America

Note: The index scores have been standardised to a scale from 0 to 100. In each index a higher score is a more favourable outcome. The 17 Latin American countries are the Ibero-American countries for which updated data were available in all six indexes: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Paraguay, Panama, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. The six indexes are the Democracy Index 2020 (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2021); the Doing Business 2020 Index (World Bank, 2021); the Freedom in the World 2021 Index (Freedom House, 2021); the Corruption Perceptions Index 2020 (Transparency International, 2021); the World Happiness Report 2020 (World Happiness Report, 2021); and the Global Health Security Index 2019 (Nuclear Threat Initiative, Johns Hopkins University, The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2020).

As seen in the table, the EU’s average score in every index is higher than the respective Latin American score. This correlates with generally higher development levels. However, our focus is on the distribution of the scores, as measured by the standard deviation. The EU tends to exhibit a lower dispersion in its outcomes, which indicates a better overall level of alignment and homogeneity among EU member states than those in Latin America. It is notable that the EU’s scores are substantially more aligned than those for Latin America in relation to democracy and the ease of doing business.

With respect to perceptions of corruption and global health security, the EU’s average values are higher, but the standard deviations are relatively similar in the EU and Latin America. This indicates that in these sectors the internal alignment among EU nations is significantly less evolved than in the other sectors, and that there are greater than usual differences between its member states. Although both the EU and Latin America exhibit a lack of convergence in these sectors, the lack of convergence in the EU is more notable given the deviations are significantly higher than in other sectors.

Finally, and surprisingly, happiness, as measured by the World Happiness Report, is more evenly distributed among Latin American countries than it is among the EU’s member states. The EU has a higher overall level of happiness, but the values are relatively similar in both geopolitical areas, with a score of 65.29 in the EU and 60.99 in Latin America.

In defence of regional integration

Our initial hypothesis was that we may get an indication of the benefits of regional cooperation by identifying more evenly distributed index scores among the highly integrated member states of the European Union. This is what the six indexes seem to suggest.

There is evidence that economic and political integration is an advantage in fighting inequality, which ranks as the greatest challenge of the 21st century on the global stage. Moreover, there are implications for global peace as countries that have similar scores due to integration, despite their cultural differences, are likely to prefer cooperation over competition.

This is why the former President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, among others, was right to label the EU a “peace project”. Latin America currently lacks this dynamic, in spite of its nascent attempts to pursue regional integration. Juncker was also right about something else: namely that the world “needs Europe”. The world needs Europe because a successful post-Brexit EU may serve as an example of the benefits that can be acquired from regional integration.

Nevertheless, even though our comparison between the EU and Latin America partially confirms our initial hypothesis, it also raises new questions. First, in terms of the observable functioning of institutions, EU countries tend to standardise upward in relation to democracy and the ease of doing business. This is a good thing as this process will foster higher social standards and reduce inequality via redistribution and protection for workers. This is one of the main achievements of the EU and it makes continental Europe one of the least unequal geopolitical areas in the world, in stark contrast to Latin America.

Second, perceptions of corruption and global health security have similar levels of alignment in the EU and Latin America. The question is why this continues to be the case despite Europe’s higher levels of integration. One possibility is that EU citizens are departing from a very high standard in their perceptions of corruption. An alternative explanation is that the EU must do much more to apply the same standards of the rule of law to all of its member states.

Third, overall levels of happiness are surprisingly similar in the EU and Latin America, in contrast to the other indexes. This may suggest that happiness is not necessarily tied to a high degree of regional integration or to the other factors measured by the indexes.

Given these findings, there is an important lesson for both Latin America and the EU. If consistent, strong and sustained relations between societies helps align their institutional framing and functioning, this is likely to lead to more efficient and faster development. Thus, regional integration is still worth the endeavour. This means first that efforts to increase cooperation between Latin American countries should continue, and second, that the community approach of the EU, rather than a ‘new nationalism’, should be taken as the model for further Latin American integration and development.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council

There are two fundamental reasons for the slower roll out of vaccines in the EU compared with the UK.

(1) Astrazenaca has delivered about a quarter of the doses it promised to the EU and almost all the doses it promised to the UK.

(2) the EU has exported about 40% of vaccines produced (with only one shipment, 250,000 doses to Australia, blocked) while the UK has exported none of its production and has indeed imported from the EU and sought to import from India.

So the EU, and the vaccine-producing member states, are putting into practice their stated values of regional and global solidarity.

However one wishes to describe the values of Brexit Britain, the UK is not really living up to its foreign policy review described by the UK foreign secretary as “Britain: a force for good in the world”.

An alternative to Mr Romberg’s explanation might be:

1. The UK was much faster in its vaccine strategy. It implemented this via commercial contracts with vaccine suppliers much earlier than the EU and also funded the development of the Oxford/Astra Zeneca at an earlier point in time.

2. The UK did not denigrate the Oxford/ Astra Zenica vaccine as did a succession of EU politicians causing their populations not to trust it. So many vaccines which could have been used in the EU, and already in the EU, were not used.

3. The UK regulators were quicker to approve the use of the various vaccines.

4. The “regional solidarity” seems to be a myth in a number of poorer EU members, for example, Hungary and Romania.

5. As for the UK being a force for good in the world, it will be interesting to assess the financial contributions of individual EU states to the COVAX initiative as compared with the UK.

6. As the world is vaccinated the cost advantage of the not for profit Astra Zeneca vaccine will be seen as a major contribution to the global good.