The credit ratings of European countries have remained relatively stable during the Covid-19 pandemic, despite a sizeable increase in public debt. Judith Arnal, Pedro Cuevas, Isabela Delgado, Javier Muñoz and Lucia Paternina of the Spanish Treasury assess why this time appears to have been different from previous crises.

Credit rating agencies play a crucial role in reducing asymmetric information in financial markets, with the ratings provided being used for a wide variety of purposes. However, financial literature provides evidence that credit rating agencies behave in an excessively procyclical manner, assigning worse credit ratings in a recession than the actual profile of the issuer would deserve.

Credit ratings are key in terms of enabling access to funding by sovereigns, financial and non-financial corporates. Thus, any additional procyclicality will unnecessarily impair access to funding sources. This situation becomes more acute when financial agents lose their investment grade rating (becoming so called “fallen angels”), triggering additional losses and fire sales. Still, even if the rating of the issuer is well above the investment grade threshold, the existence of sovereign ceilings can also lead to an inadequate valuation of the credit profile of an issuer. In a nutshell, excessive procyclicality of ratings is a clear issue from a financial stability perspective.

Rating assessments during the Covid-19 pandemic

The pandemic caused by the Covid-19 crisis has led to a setback in the world economy, which is unprecedented since the Second World War. However, when compared with the financial crisis that started back in 2008, the number of downgrades, both for sovereigns and corporates, has been significantly lower. Thus, it turns out that this time has been different.

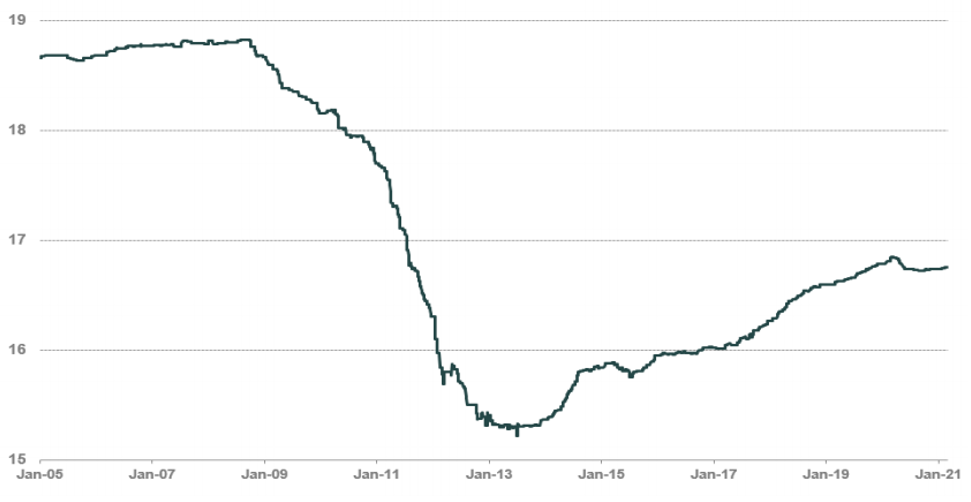

Starting with sovereigns, as can be seen in Figure 1, during the previous financial crisis, there was an average decrease of four notches between 2008 and 2013. Yet, the decrease was irregular, with a significant worsening between 2010 and 2012 that came to a relative halt as of July 2012, thanks to the stabilising effect of Mario Draghi’s commitment to do “whatever it takes”. The recovery of credit ratings started in 2014, but by the beginning of March 2020, it still fell short of pre-crisis levels. In fact, at the beginning of March 2020, the average rating of euro area sovereigns was firmly in the middle ground between the beginning and the end of the financial crisis: two notches above its 2013 levels, but still two notches below early 2008.

Figure 1: Eurozone sovereign average rating between 2005 and 2021

Note: The figure shows the average credit rating for members of the Eurozone between 2005 and 2021. The ratings are shown on a scale between 21 (AAA, stable) and -1 (SD). Source: DBRS, Fitch, Moody’s and S&P.

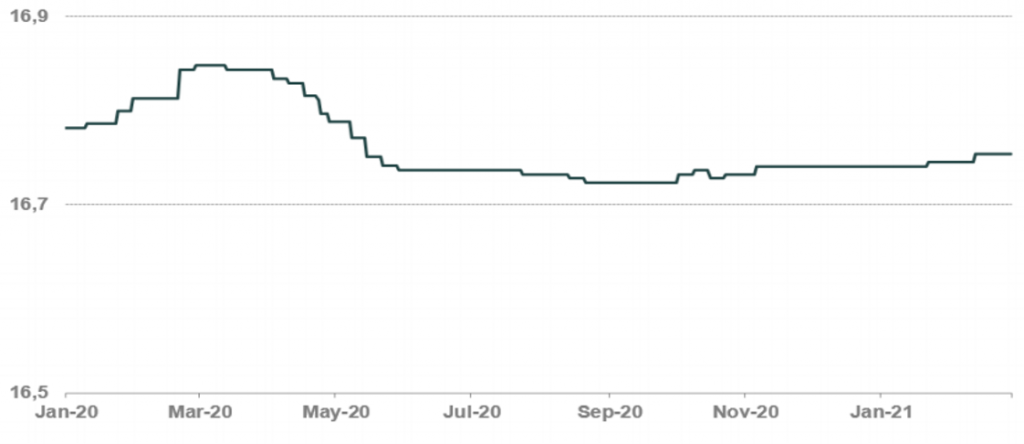

However, during the Covid-19 crisis, the adjustment has taken place especially in terms of outlook changes, with only a few rating downgrades in the euro area, as shown in Figure 2, and an even higher number of rating upgrades, the latest one being the upgrade of both rating and outlook by S&P of Greece.

Figure 2: Eurozone sovereign average rating during the Covid-19 pandemic

Note: The figure shows the average credit rating for members of the Eurozone from January 2020 until March 2021. The ratings are shown on a scale between 21 (AAA, stable) and -1 (SD). Source: DBRS, Fitch, Moody’s and S&P.

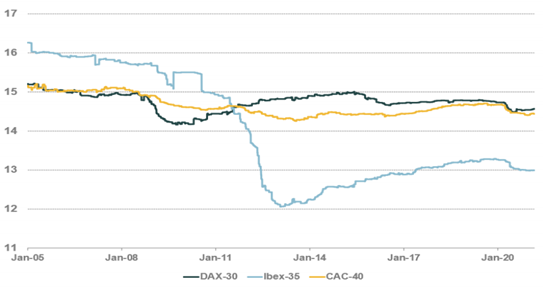

As far as corporates are concerned, initially, with the 2008 financial crisis, they were not as affected as sovereigns. Yet, the situation changed with the start of the sovereign debt crisis and the intensification of the bank-sovereign feedback loop. However, the situation has not been homogeneous in Germany, France and Spain, due to the sovereign ceilings, the relative weight of the banking sector in the major stock indexes of these member states and other idiosyncratic factors.

During the Covid-19 crisis, starting in March 2020, corporates suffered only a slight deterioration in their credit rating, in many cases only through an outlook downgrade or a rating watch. Changes were of around a quarter of a notch. The Dax-30 was the first to hit the ground, in June 2020, while the CAC-40 and the Ibex-35 did so in December. Now, the situation seems rather stable, though in the case of the Dax-30, a slight improvement has been registered. The evolution of the credit ratings of sovereigns and corporates can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Stock indexes average ratings between 2005 and 2020

Note: The figure shows the average stock index rating between 2005 and 2020. The ratings are shown on a scale between 21 (AAA, stable) and -1 (SD). Source: DBRS, Fitch, Moody’s and S&P.

There are a number of reasons that can explain why ratings have been substantially less procyclical during the Covid-19 crisis compared to the previous financial crisis.

First, while it is natural to observe negative rating actions by credit rating agencies during recessions, each crisis is unique, and rating actions should be tailored to their specific circumstances. In this case, the idiosyncratic nature of the health and economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic is a likely explanatory factor behind the different role of credit rating agencies in this crisis.

Second, another aspect that has made a difference in the Covid-19 crisis has been the decisive policy response. At no point during the pandemic was there a debate about the need to support the economy or were austerity measures on the table. On the contrary, it has always been clear, both for governments and other authorities, that support measures should be taken, and the debate has been rather focused on the form and design of the measures and their scope. At the European level, the response to the crisis has come in the form of fiscal, monetary and macro-prudential measures.

Another differentiating element is the ratings’ starting level. In 2007, both sovereign and corporate ratings were at very high levels, thus leaving room for further downgrades. After the financial crisis and the eurozone debt crisis, the recovery to previous rating levels has been very gradual and by the beginning of 2020, in general, not even half of what was lost between 2007 and 2014 had been recovered.

Fourth, in practice, sovereign ratings act as rating ceilings for most domestic issuer ratings. Therefore, sovereign rating downgrades can result in widespread credit downgrades. In comparison with the previous financial crisis and the eurozone debt crisis, when a high number of sovereign ratings fell by several notches, for the time being, only three have seen their ratings lowered since March 2020, while another four have improved them.

Finally, the strengthening of the regulatory and supervisory framework for credit rating agencies in the EU via the reforms of 2009, 2011 and 2013, has undoubtedly helped reduce any procyclical behaviour in credit rating assessments. Still, though these measures have meant good progress in ensuring financial stability, credit ratings still play a key role in investment policies and in the operational framework of central banks, which still raises macro-prudential issues.

The reduced procyclicality observed during the Covid-10 crisis is good news in terms of financial stability. Once the Covid-19 crisis has fully come to an end, a further analysis would be welcome. Moreover, in order to corroborate that a change in the pattern of procyclical ratings has indeed taken place, this analysis should be run and tested against a more traditional, endogenous type of crisis. Still, we hope it will take us several years before this hypothesis can be tested.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying working paper which was recently presented at a Bruegel event.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Paul Fiedler on Unsplash / Matthew Henry on Unsplash