The adoption of information and communications technology has given rise to a skill bias: those with higher-level skills have had their employment prospects enhanced, while those with lower-level skills have been more likely to find their jobs replaced by machines. Drawing on evidence from Germany, Sebastian Diessner, Niccolo Durazzi and David Hope illustrate that this skill bias has had a far wider societal impact than is commonly recognised, with many of the core institutions that underpin advanced political economies being adapted to enable firms to meet the new challenges of the knowledge economy.

The transition from Fordism to today’s ‘knowledge economy’ has seen extensive technological and institutional change across the globe. Among other things, it has been marked by the widespread adoption of information and communications technology (ICT) in virtually all spheres of economic and societal life.

As labour economists have argued prominently, the widespread adoption of ICT in the workplace has given rise to a ‘skill bias’: that is, higher-level general skills (as obtained through higher education) are complementary to ICT, whereas lower-level skills are more likely to be substituted by computers or machines. As a result, highly-skilled workers have experienced substantial wage premia and improved employment prospects in the knowledge economy, at the expense of workers lower down the skills distribution.

In a new study, we argue that this skill bias has had even wider societal ramifications, affecting some of the core institutions that underpin advanced political economies. As firms grapple with the risks and opportunities that stem from technological change, they have come to compete for increasingly scarce highly-skilled personnel. In response, governments and social partners have sought to adapt institutional frameworks to better enable firms to meet the mounting challenges they face in the knowledge economy. We refer to this phenomenon as ‘skill-biased institutional change’ and illustrate it in the context of an eminent advanced economy: Germany.

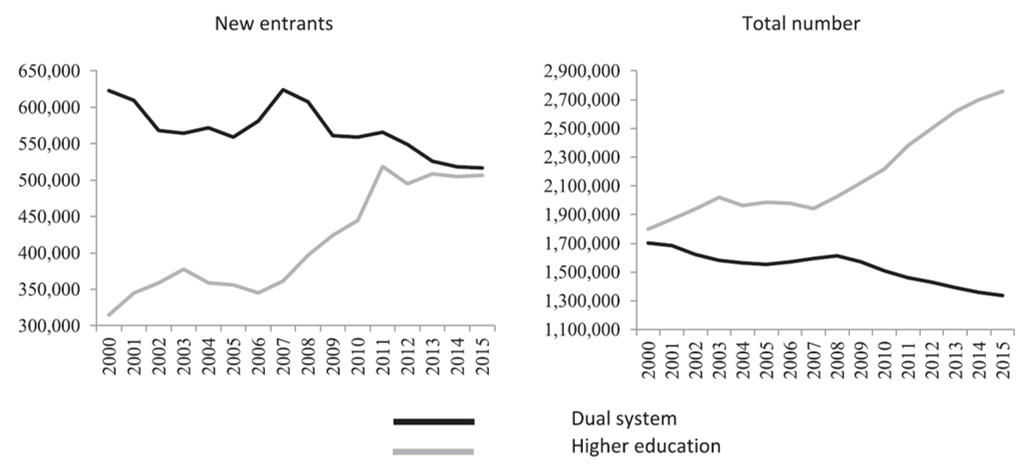

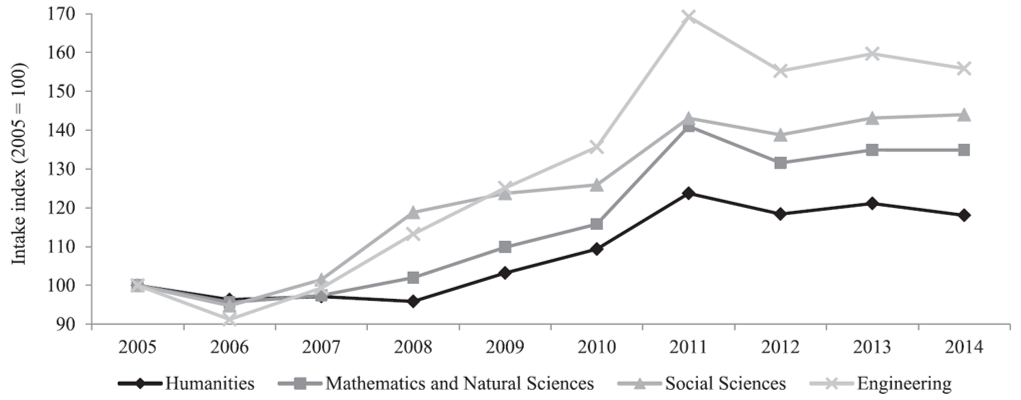

Our analysis shows that the German political economy and its export-oriented manufacturing sector have undergone fundamental technological change since the turn of the century. Simultaneously, core institutions in the realms of skill formation, industrial relations, and social policy have been reformulated to meet firms’ increasing demands for workforces with higher-level general skills (especially in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics, or STEM, subjects). This has been reflected, among others, in both the size and the relative intake of new entrants to higher education in Germany since 2000 (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Size of higher education and dual vocational training systems in Germany (2000-2015)

Source: Diessner, Durazzi and Hope (2021)

Figure 2: Relative intake of students by discipline in German higher education (2005-2014)

Source: Diessner, Durazzi and Hope (2021)

Moreover, whereas a profound liberalization of Germany’s labour market institutions and welfare state against the resistance of trade unions has been documented in the extant literature, we find that firms have sought to exploit these developments not merely to cut costs at the lower end of the skills distribution, but also to redeploy wages and non-wage benefits to attract and retain the highly-skilled workers that have become central to production strategies in the knowledge economy (see Table 1).

Table 1: Share of total labour compensation by skill group in German manufacturing (2002 and 2017)

Note: University graduates refer to those with educational attainment at ISCED levels 5 and 6. Figures in parentheses refer to the number of persons employed in each skill group. Source: Diessner, Durazzi and Hope (2021)

These findings have implications for our understanding of the underlying logic of institutional change in advanced democracies. While existing perspectives argue that the key dividing line in labour markets today runs between core and peripheral sectors (as argued by dualisation scholars) or between capital and labour (as argued by liberalisation scholars), we show that skill levels constitute an underappreciated site of segmentation across workforces in the knowledge economy. Viewed through this lens, capital and highly skilled workers emerge as the winners of technological and institutional change, while labour lower down the skills distribution is increasingly losing out.

More research is needed to substantiate whether the patterns we observe in Germany can be observed across Europe and beyond. There is good reason to believe this may be the case, however, as many advanced economies (including the Nordic countries and the Netherlands) have moved further out of traditional manufacturing than Germany and are increasingly focused on high-value-added services and ICT-intensive manufacturing. We thus hope that our new perspective can spawn a fruitful research agenda exploring ‘skill bias’ as a key driver of institutional change during the transition to the knowledge economy.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper at Politics & Society

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Scott Graham on Unsplash