In a new study, Tim Vlandas and Daphne Halikiopoulou present new empirical evidence about the effect of jihadist terrorist attacks on far-right party preferences in Europe. Their findings suggest that terrorist attacks are unlikely to decisively change party preferences, despite attracting significant public attention and affecting political attitudes.

Terrorism has become an increasingly salient issue across Europe in recent years. This presents far-right parties with the opportunity to link this issue to the main issue they “own”, namely immigration, to expand their electoral appeal. Many far-right parties utilise this opportunity by framing terrorism as an immigration issue: they often place terrorist incidents within a broader context of a value conflict and argue that terrorism is enabled by mass immigration. How successful is this strategy?

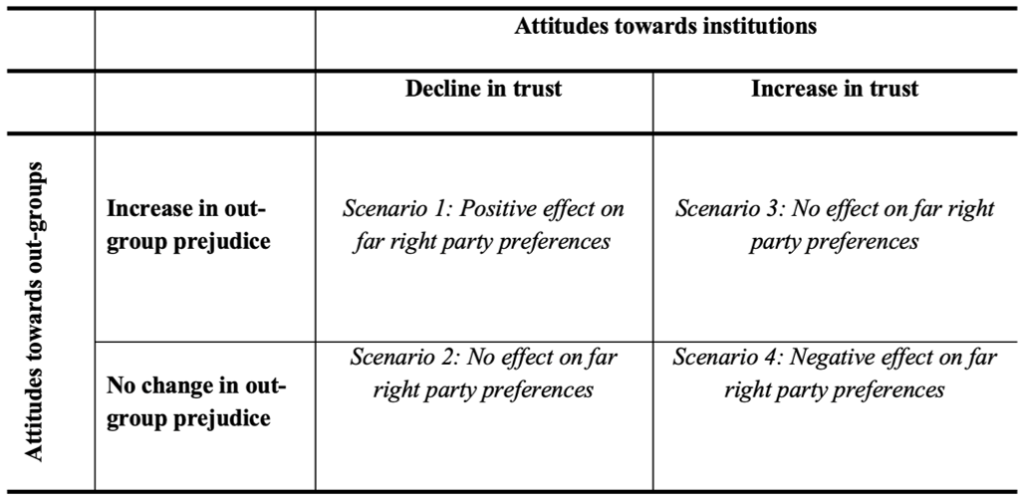

In a new article, we theorise and test three distinct hypotheses about the impact of jihadist terrorist attacks on far-right preferences, taking into account different combinations of potential attitudinal changes including out-group prejudice and trust in institutions, which have been linked with party support. Table 1 below summarises the ways in which distinct combinations of these two types of attitudes may lead to four potential scenarios.

Table 1: Conceptualising the relationship between jihadist terrorism, attitudes and far-right party preferences

Source: Vlandas T. and Halikiopoulou D. (2024)

First, we expect a simultaneous increase in out-group prejudice and institutional distrust resulting from a jihadist terrorist attack to benefit the far right (Scenario 1). Second, if jihadist terrorist attacks either (a) simultaneously increase out-group prejudice and institutional trust or (b) simultaneously reduce out-group prejudice and institutional trust, then we should expect a null (i.e. non-significant) effect on far-right party preferences (Scenarios 2 and 3). Under both these latter circumstances, the two attitudinal dimensions cancel each other out.

Third, if jihadist terrorist attacks increase institutional trust but not out-group prejudice, then they are likely to deter people from far-right parties when these are not in government, favouring instead mainstream parties and/or the incumbent as a result of a “rally around the flag” effect (Scenario 4).

In sum, an increase in far-right party preference is likely only when out-group prejudice increases and trust in institutions decreases. Under the remaining three scenarios, far-right party preference will either stay the same or decrease, either because out-group attitudes remain unchanged or because institutional trust increases.

An “unexpected event during survey design” in four European countries

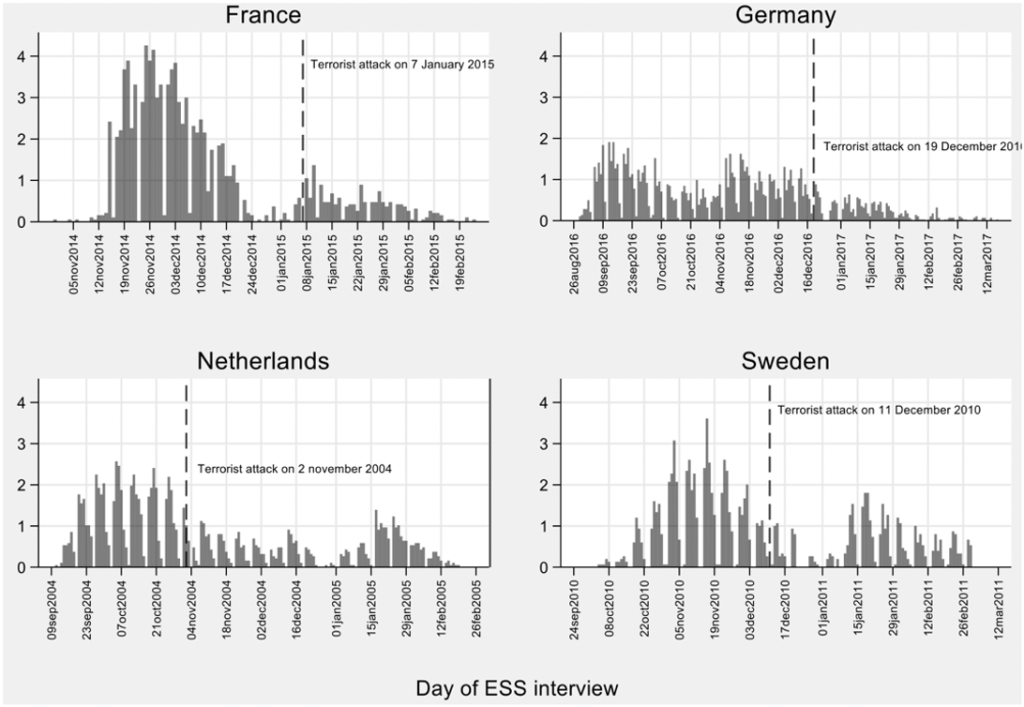

To test the potential effect of jihadist terrorist attacks on far-right preferences we use the “unexpected event during survey” research design, which exploits the occurrence of a salient and unforeseen event during the fieldwork of a public opinion survey. Specifically, we merge data from the Global terrorism dataset and the European Social Survey (ESS) to identify those terrorist attacks that occurred during the ESS fieldwork period.

Four jihadist terrorist attacks match this combined criterion: attacks in the Netherlands (2004), Sweden (2010), France (2015) and Germany (2016) (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Jihadist terrorist attacks as a random shock to survey respondents

Source: Vlandas T. and Halikiopoulou D. (2024)

While these four attacks varied in intensity, number of casualties and target range, they shared certain important similarities which suggests they are comparable. First, all attacks were cultural-ideological in nature, perpetrated in the name of Islam and specifically targeting the western democratic way of life and its ideals. Second, in all cases the perpetrator(s) had links to broader Islamist networks. Third, while two of the attacks were indiscriminate (Germany and Sweden) and the remaining two were targeted towards specific individuals (Netherlands) or organisations (France), they all aimed at harming civilians for their beliefs, as well as damaging private property. Finally, all attacks received significant media and public attention.

These commonalities in terms of the motives and background of the perpetrators suggest all these attacks would likely strengthen far-right party support through the prejudice mechanism, which expects an increase in anti-immigration attitudes. All attacks had the potential of having an intended intimidating effect on the public, potentially eliciting blame attributions to foreigners and Muslim individuals perceived as foreigners regardless of their citizenship status, and triggering a range of negative emotions including anxiety, fear and anger.

The non-effect of terrorist attacks on far-right party preferences

While jihadist terrorism is often seen as an opportunity for far-right parties to capitalise on anti-immigrant and Islamophobic narratives, we find no statistically significant effect of jihadist terrorist attacks on self-declared proximity to the far right. Consistent with this null effect, we do find some evidence supporting both the prejudice and trust mechanisms.

This suggests the two dimensions may be cancelling each other out, since greater prejudice increases support for the far right while the opposite is true for higher trust. In terms of prejudice, the effect of jihadist terrorist attacks on overall negative attitudes towards immigrants and refugees is positive and statistically significant; in terms of trust, jihadist terrorist attacks are associated with greater confidence in parliament and satisfaction with government.

Our findings contribute to our understanding of how terrorism might impact on domestic politics. First, we provide strong empirical evidence that in the western European context, jihadist terrorist attacks are unlikely to decisively change party support, despite potential changes in political attitudes.

The absence of a direct causal link between terrorist attacks and far-right party preferences in our sample challenges the idea that jihadist terrorism fuels right-wing extremism in the European context. This also highlights significant variation between European countries, where terrorist attacks are perceived as being instigated by foreign groups even if the perpetrators are homegrown militants, and non-European countries such as Turkey or Israel, where terrorist incidents are largely caused by domestic armed conflicts.

Second, heterogeneity analysis reveals interesting variation among respondents. Individuals typically associated with far-right party support, such as the unemployed, are deterred from far-right parties after jihadist terrorist attacks. Conversely, jihadist terrorist attacks have a positive effect on individuals not typically associated with the far right, for example respondents with tertiary education.

Certain socio-demographic and attitudinal characteristics such as gender and subjective income insecurity do not seem to moderate the effect of jihadist terrorist attacks, although they have been linked to far-right party support. This suggests that while there may not be an average population-wide effect, there may be a composition effect resulting in changes in the make-up of the pool of people who feel close to the far right. It is plausible that some individuals are galvanised by terrorist attacks, while others are simultaneously deterred. In the longer run, this might lead to changes in party positions.

Third, our findings respond to recommendations for more visible reporting of nonsignificant results and illustrates how these may advance debates in the social sciences. We contribute to the understanding of the ways in which citizens behave politically in the aftermath of jihadist terrorist attacks in western Europe by showing that despite triggering some changes in attitudes, jihadist terrorist attacks are unlikely to augment far-right party support.

This is important, particularly in the context of a far-right populist hype, as the dissemination of research impacts not only academia but also the policy world. Far-right parties attempt to capitalise on terrorist attacks using perceived shifts in political preferences as justification for their exclusionist platforms. In turn, centre-right parties often adopt co-optation strategies based on similar perceptions about public preferences and the ensuing need to “re-capture” this electorate from the far right. If we are right, at least in Europe, their bids are exaggerated and potentially self-defeating. Responses to jihadist terrorist attacks may be limited in size and duration offering less fertile ground for far-right mobilisation than is often assumed.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Perspectives on Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Hadrian / Shutterstock.com