Ronald Inglehart’s ‘value change’ theory states that as countries develop and meet the material needs of their citizens, the views of their voters should increasingly come to be shaped by ‘postmaterial’ concerns. Using manifesto data from 1990 to 2019, Federico Trastulli tests whether this principle also holds for the platforms of political parties. He finds that with the exception of green parties, western European parties still place substantially more emphasis on material issues in their manifestos.

One of the many contributions of Ronald Inglehart, who passed away on 8 May, was the theory of ‘value change’. This posits that as advanced industrial societies increasingly meet the material needs of their citizens, the values, attitudes, and political opinions of these citizens will come to be shaped more prominently by non-material questions.

Despite the popularity of this theory, a sizeable portion of the political science literature still focuses on the fundamentally materialist ‘left-right’ axis when explaining political behaviour. Most of these studies have tended to assess the so called ‘demand side’ of electoral politics, namely the role that values, attitudes, and opinions have in shaping voting outcomes. Yet, the ‘supply side’ of political competition, namely the positions taken by political parties, is also potentially important. For instance, if the theory of value change held true, it would be possible to observe a progressive emergence of ‘postmaterialist’ issues in the platforms of political parties.

The multidimensional policy space present in western Europe offers an ideal environment to put this theory to the test. In a new study, I use data from the Manifesto Project (MARPOR) to assess whether materialist or postmaterialist issues were more salient in the national election manifestos published by parties in western Europe between 1990 and 2019.

I find little evidence for the value change hypothesis in my analysis. Western European political parties generally emphasised materialist issues significantly more than postmaterialist ones in their electoral manifestos during the period covered in the study. Indeed, over 85% of the manifestos I analysed placed greater emphasis on materialist issues than they did on postmaterialist themes.

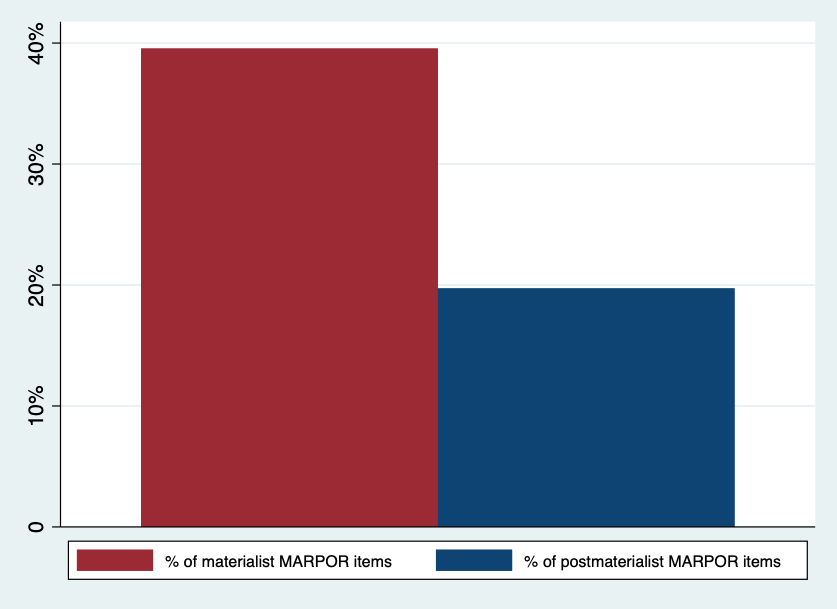

On average, materialist themes were emphasised twice as much as postmaterialist ones in any given manifesto. In total, just under 40% of an average manifesto was focused on materialist issues, while just under 20% was dedicated to postmaterialist issues. Figure 1 below provides an illustration of these findings.

Figure 1: Average emphasis on materialist and postmateralist issues in western European party manifestos (1990-2019)

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying study.

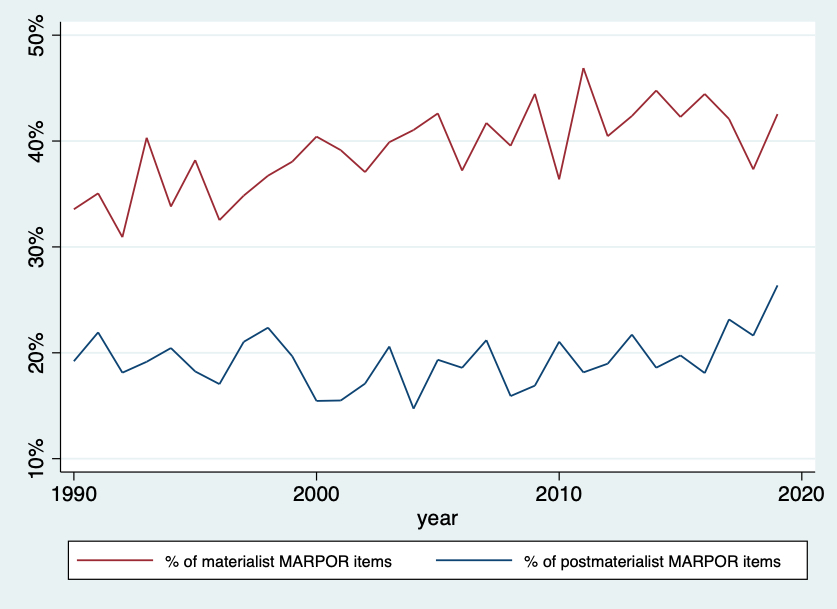

This raises the question of how this balance has changed over time. Contrary to the value change theory, the distance between the emphasis on materialist and postmaterialist issues in manifestos has remained relatively consistent over the last three decades, as shown in Figure 2 below. During the early 1990s, the gap was closer, but still sizeable. On average, postmaterialist issues have hovered around the 20% mark, with no discernible trend until the late 2010s, when there is an observable rise. This may be linked to issues such as Europe’s migration crisis and the increasing prominence of environmental concerns. In contrast, there has been a clear increasing trend in the emphasis on materialist issues in manifestos.

Figure 2: Change in the average emphasis on materialist and postmateralist issues in western European party manifestos over time (1990-2019)

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying study.

I also separated manifestos into four geographic clusters. In every cluster, materialist issues received greater emphasis, however there were some interesting differences between each of the four areas. As Figure 3 below shows, the gap between materialist and postmaterialist issues was narrower in Continental Europe than in the other areas. A potential explanation for this is that the Continental Europe area features several radical right parties, such as the Front National in France and the Alternative für Deutschland in Germany, as well as green parties, for instance in Austria, Belgium and Germany.

Figure 3: Average emphasis on materialist and postmateralist issues in western European party manifestos by geographic area (1990-2019)

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying study.

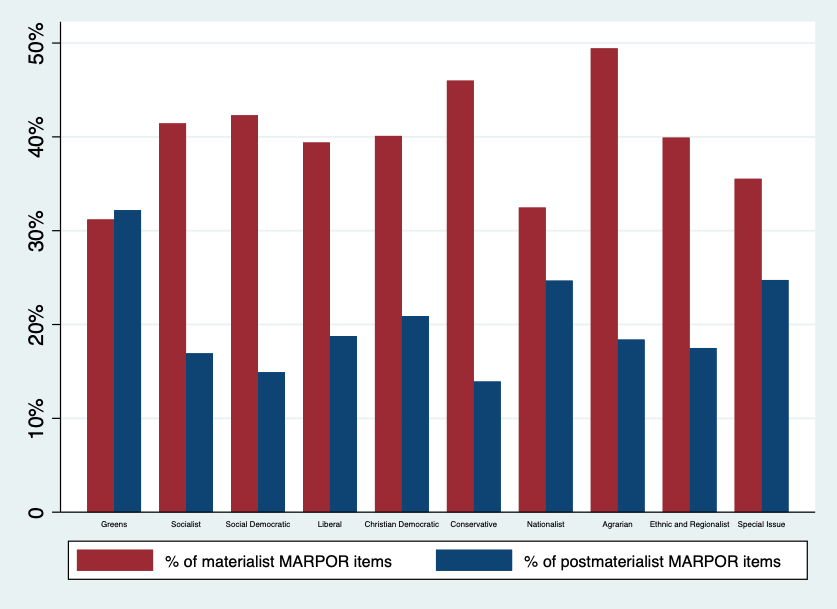

Finally, when the manifestos are separated into different party families, green parties can be seen as a clear outlier to the general trend. As Figure 4 below shows, these parties tend to emphasise postmaterialist issues more than materialist ones in their manifestos. This is logical as the focus of green parties is on protecting the environment, which classifies as a postmaterialist issue.

Nationalist and special issue parties also tend to have a more balanced split between materialist and postmaterialist issues than the parties in other groups. This is unsurprising as nationalist parties are located at one end of a ‘postmaterialist axis’ ranging from ‘green/alternative/libertarian’ to ‘traditional/authoritarian/nationalist’ positions. Similarly, special issue parties, by definition, generally mobilise support around issues that lie beyond the boundaries of left-right politics. In contrast, mainstream party families have a substantial gap between materialist and postmaterialist issues in their manifestos, which is expected given they are strongly associated with traditional left-right issues.

Figure 4: Average emphasis on materialist and postmateralist issues in western European party manifestos by party family (1990-2019)

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying study.

Over the past thirty years, almost all western European parties have emphasised materialist issues significantly more than postmaterialist issues in their manifestos – and increasingly so over time. This conclusion seemingly contradicts the postmaterialist value change thesis with respect to the supply-side of electoral politics. Yet, this picture can only be partial. A key question that remains is whether these findings also hold for the demand-side of electoral politics, namely the views of voters.

One the one hand, if a similar trend were observed on the demand-side, this would imply we should reject the value change thesis in its entirety. On the other, if citizens have indeed adopted a more postmaterialist outlook, then it would raise several questions concerning the responsiveness of parties and what ultimately shapes their strategic behaviour. Either way, these dynamics surely constitute fertile ground for future research.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper at Italian Political Science

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Bündnis 90/Die Grünen Nordrhein-Westfalen (CC BY-SA 2.0)