Why does the gender balance among politicians vary so substantially across different locations? Drawing on a new study, Moa Frödin Gruneau illustrates that the historical persistence of traditional family structures has a clear relationship with the number of women in politics today.

Despite numerous attempts over the years to increase the share of women among politicians, politics more often than not remains a man’s game. But why is the gender imbalance in political assemblies across the world so difficult to change?

Previous research has suggested numerous reasons for the underrepresentation of women in politics. These include that women have less ambition than men, that voters prefer male candidates, and that women face larger structural constraints, such as having to combine a career with homemaking. However, it remains an open question as to why we see variation in the level of constraints women face, and why the demand from voters for women in politics varies across time and place.

History matters

In a new study, I focus on the historical persistence of traditional family structures. The reasons to do so are threefold. First, history matters for present day gender roles. Second, gender-traditional norms and family structures put constraints on women’s careers. Third, attitudes toward gender roles are transmitted across generations.

My results show that some of the variation in the gender composition of political assemblies can be explained by deeply rooted historical family structures. More specifically, using the case of local politics in Sweden, I combine data on marriage patterns from the 18th and 19th centuries with present day data on local political representation, and find that where family formation patterns were more traditional in the past, there are fewer women in politics today.

There are a number of reasons to have confidence in these results. First, focusing on a single country makes it possible to hold several competing explanations constant. For example, by focusing on variation within Sweden, we can be sure that differences in electoral systems do not explain the differences between different localities. Second, by using historical data from before the introduction of democracy, we can be sure that the reason for persistence cannot simply be that more women in politics leads to women-friendly social structures. Third, I rely on high quality data from population registers for both historical and present-day measurements.

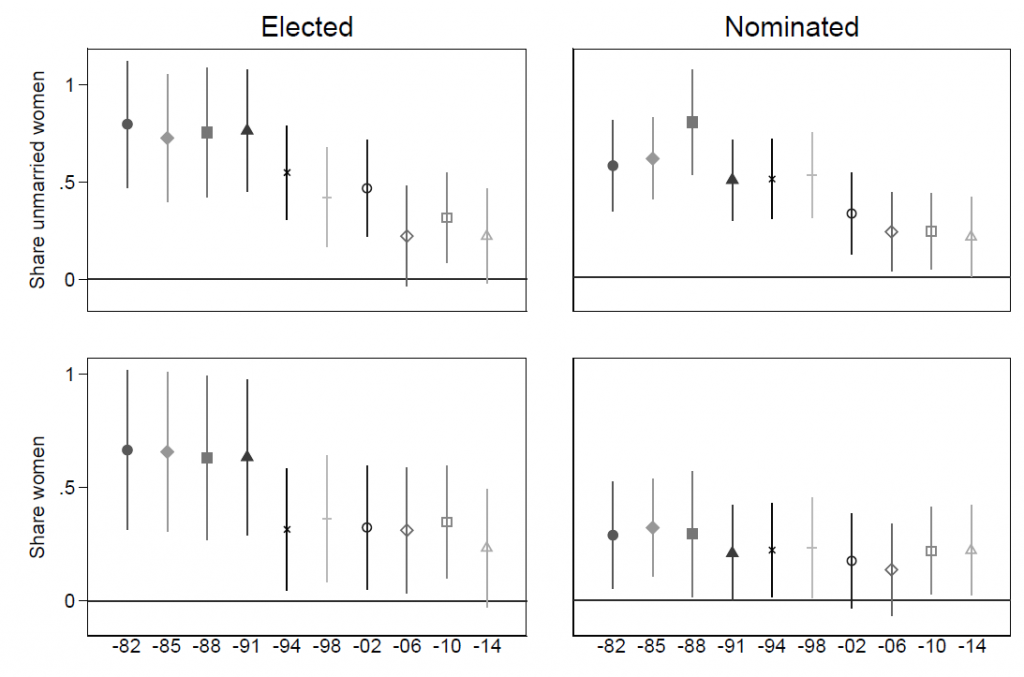

Figure 1: Historical gender norms and gender balance in local politics

Note: Coefficients from bivariate regression models, by year, all elections 1982–2014. Source: Statistics Sweden and Tabellverket.

I study correlations between three different things. First, as illustrated in Figure 1, I find that where the share of women in the population was high and the share of unmarried women was high in the 18th century, the share of women in politics is relatively high today. Second, present day marriage patterns are correlated with present day gender balance in politics. Where marriage rates are high and divorce rates are low, there are fewer women in politics. Third, historical marriage patterns are correlated with present day marriage patterns. Where the share of unmarried women was high in the past, the marriage rates are more likely to be low today.

When it comes to alternative explanations for this relationship, the long time span makes it difficult to rule out other explanations for the persistence of these social structures. An additional analysis, does, however, show that things such as labour market structure and early industrialisation have limited impact on the relationship between marriage and women’s political representation.

Change remains possible

What can we learn from the study? Well, if historical social structures matter, this may explain not only the variation we see in political representation but also things commonly seen as explanations to such variation. For example, persistence of traditional historical norms may well explain differences in levels of political ambition among women, differences in the structural constraints that women face, and differences in voter demand for women in politics.

Does this historical persistence mean that nothing can be changed? Interestingly, the correlations with the 18th century are much stronger in the 1980s than in the 2010s. Thus, the results not only show that gender inequalities can be persistent over centuries, but also that a lot can change in just a few years.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in Politics & Gender

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: CC-BY-4.0: © European Union 2021– Source: EP