Digitalisation has profound implications for employment, but are there meaningful differences in how European countries view the process? Drawing on a new study, Matteo Marenco and Timo Seidl show how discourses on digitalisation vary across Europe.

From the precarity of platform work to the rise of robots, digitalisation is fundamentally changing the nature of work. But as social scientists have been quick and correct to point out, digitalisation is not a force of nature that just sweeps over societies. Rather, it is shaped by how policymakers react to it: from how much they invest in digital skills to how they regulate new forms of work.

These reactions have not been the same everywhere. In the case of Uber, for example, responses have ranged from a welcome embrace and accommodating regulatory adjustments to complete rejection and legal bans. However, it is not just that the responses were different. It is also that the digitalisation of work is not even the same problem everywhere. Take again the example of Uber. In some countries, debates centre around labour law. In others, the debate is about taxation. And in still others, it’s about competition law.

What this teaches us is that digitalisation is not only regulated differently, but also talked about and thought about differently. And that these differences are reflective of underlying institutional differences that shape and constrain how actors view digitalisation. If a country has a generous tax-based welfare system, it is more likely to view the rise of platform companies as a taxation issue, rather than simply a labour law issue. Digitalisation is thus not necessarily a common shock that affects all societies in the same way. Rather, it is “refracted into divergent struggles over particular national practices”.

In a new study, we build on this theoretical argument and empirically investigate how digitalisation is framed and fought over in eight European countries: France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the UK. We collected and automatically translated several thousand newspaper and policy documents on the digital future of work to investigate, respectively, the communicative discourse between policymakers and the public and the coordinative discourse among social partners. The documents were either on the emergence of new forms of online and offline work intermediation through digital platforms (the ‘gig economy’); or the growing use of advanced digital technologies like artificial intelligence to further rationalise the production process (the ‘new knowledge economy’).

We used several text-as-data methods to capture both the tone (sentiment analysis) and the content of discourse (keyword-extraction methods, topic modelling). We also relied on interviews and qualitative analysis of documents to not only interpret the quantitative results but also to uncover the agency actors have within a given institutional context. We find clear ‘country effects’ in national discourses on the digital future of work. Not only are some much more positive than others. They also focus on very different issues.

The discursive construction of the future of work

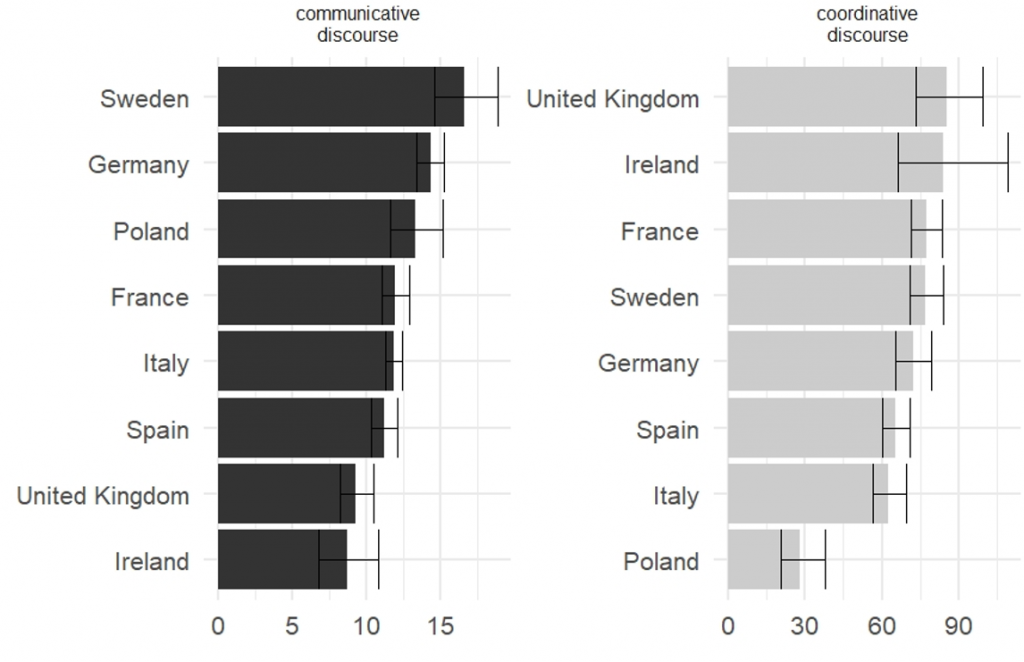

Let’s start with the tone of discourse. The sentiment of words is a good proxy for a country’s view of digitalisation: is it perceived as something bad, threatening, and destructive? Or as something good, promising, and useful? Figure 1 shows the results of our sentiment analysis. It shows, for example, that the discourse in Sweden is very positive, reflecting Sweden’s long-standing tradition of proactively and inclusively adapting to technological change. This makes digitalisation a lot less scary. “In Sweden”, as the then Swedish Minister for Employment and Integration, Ylva Johansson, put it, “if you ask a union leader, ‘Are you afraid of new technology?’ they will answer, ‘No, I’m afraid of old technology. The jobs disappear, and then we train people for new jobs’”.

Figure 1: Sentiment analysis of discourse on digitalisation in selected European countries

Note: The figure gives an indication of how positive the discourse on digitalisation is in each country. Positive views toward digitalisation are reflected by a larger score.

In the UK and Ireland, by contrast, the public is much more worried about the effects of digitalisation on an already quite precarious labour market. In this context, the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain, for example, could successfully dramatise gig work by arguing that digitalisation “isn’t just about the gig economy. All business is going more and more digital, leaner and leaner. Next, it will be banking and retail. These bad practices have to be stopped now”. Governments and businesses, on the other hand, are quite sanguine about technological change, hoping to capitalise on the relatively strong position of Irish and UK companies in digital sectors.

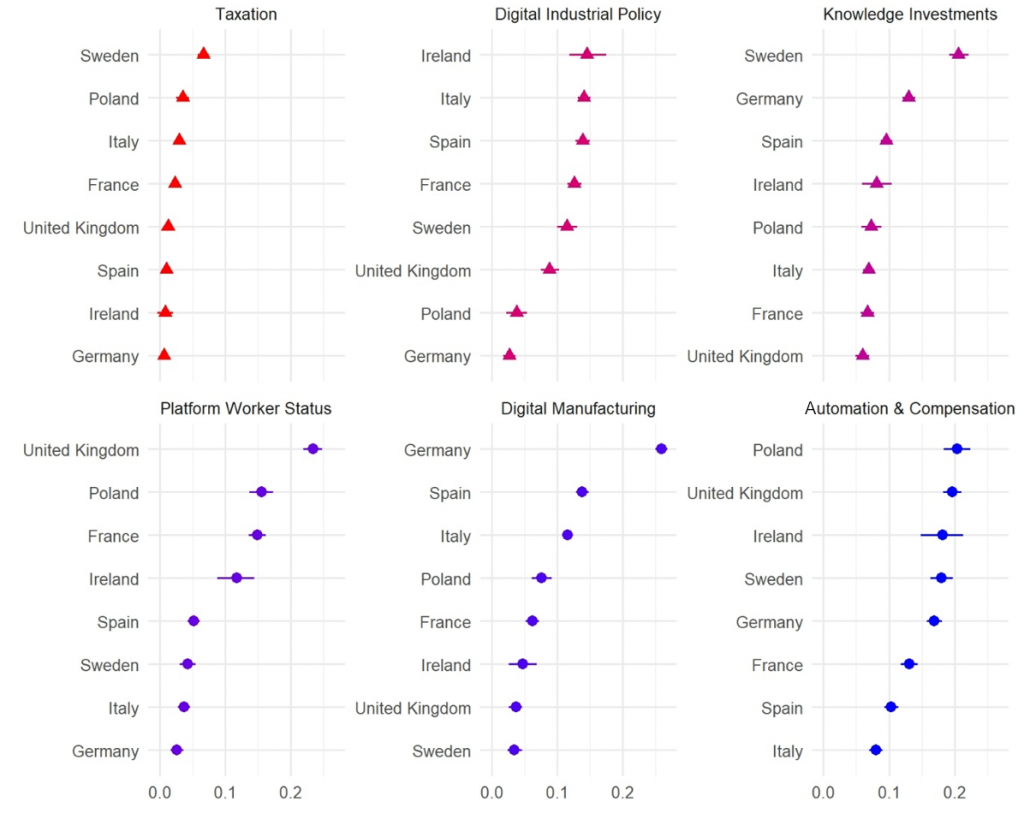

Regarding content, we also find marked differences in what countries perceive to be the pressing issues. Figure 2 shows the prevalence of different topics. We again see that Sweden focuses on taxation and investments in knowledge-based capital like education, epitomising concerns over the welfare state but also a future-oriented, embracing view of digital change. In the UK, the focus is much more on the status of platform work and the compensation of workers in response to automation, expressing a more defensive view of digitalisation. In Germany, meanwhile, the focus is on digital manufacturing, reflecting the country’s concern with its industrial sector and intense debates around Industry 4.0.

Figure 2: Prevalence of topics in discourse on digitalisation in selected European countries

Note: Estimated effect of country variable on the prevalence of topic clusters. Colour gradients indicate the ratio of the estimated effect of the discourse type variable, with red colours representing a higher conditional expectation to find the respective topic packages in coordinative (as opposed to communicative) discourses, and blue colours representing the opposite. Triangles indicate that the effect of the coordinate discourse was stronger than the effect of the communicative discourse, i.e. that the ratio of the two was greater than 1.

What is striking about Germany is that various actors – like the Ministry of Employment but also Unions – have tried to meet the challenges of digitalisation head on, instead of being defensive about them. This goes to show that actors have the discursive agency to reframe debates along new lines. In the case of Germany, social partners managed to focus the debates on issues that they could find common ground on, such as flexible working time, training, or data protection. This is reflected in Figure 3, which shows pairs of words that are central to the discourse in each country.

Figure 3: Most important keywords in the discourse on digitalisation in selected European countries

Note: Keywords across countries, with most important keywords for the communicative (black) and coordinative (grey) discourses.

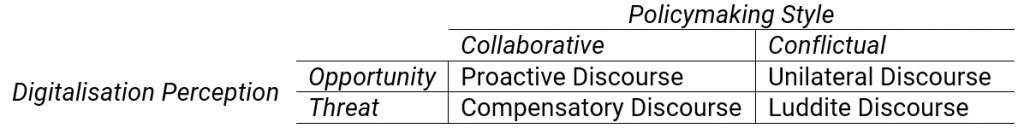

To summarise, we find clear country differences in how digitalisation is discursively constructed. Moreover, these differences reflect institutional differences, with some limited leeway for discursive agency. Table 1 distinguishes between four ideal-typical discourses, depending on whether digitalisation is viewed as a threat or as an opportunity and whether the policymaking style in a country is collaborative or conflictual. For example, if the policymaking style is collaborative and digitalisation is viewed as an opportunity, a proactive discourse dominates in which digitalisation is embraced and the emphasis is on investments that help workers and companies survive and thrive in a digital economy.

Table: Four ideal-typical discourses on digitalisation

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper.

Understanding the terms on which digitisation is framed and fought over helps us understand how and why countries react to it the way they do – and thereby shape and refract one of the most important transformations of contemporary economies and societies.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the European Political Science Review

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: ThisisEngineering RAEng on Unsplash