The EU has made a commitment to promote LGBTI rights internationally. Yet as Markus Thiel explains, the EU’s strategy has often lacked coherence, not least due to differing views among member states. Drawing on a new book, he outlines an approach for rethinking the EU’s role in LGBTI rights promotion.

The EU emphasises human rights, including for LGBTI individuals, in its internal and external policies and thus sets a powerful example globally. Yet a number of disputes over these rights policies and the way they are promoted have emerged in bilateral relations between the EU and other states in recent years. What are the causes for these tensions, and how can they possibly be mitigated?

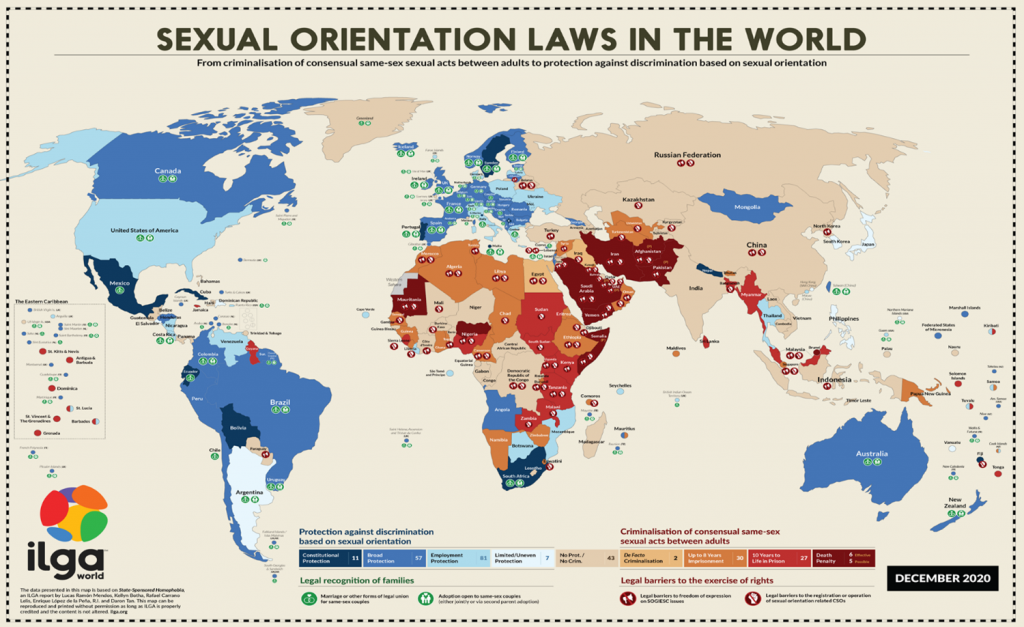

Given Europe’s colonial history, the fact that the bloc is collectively the world’s largest provider of development assistance and the increased politicisation of LGBTI individuals (see the ILGA map below), it is important to assess how the EU and its members promote LGBTI rights internationally. In a new book, I argue that while the EU contributes to a rights-enabling global environment, its often incoherent, highly visible and normative diffusion strategy evokes norm contestation. A self-reflective reassessment of the EU’s external LGBTI rights promotion could help avoid these negative unintended consequences, and address human rights deteriorations more sustainably within often broader democratic regressions.

Figure: Sexual orientation laws in the world

Credit: ILGA World

The EU’s institutions attempt to jointly formulate and implement guidelines for the external promotion of LGBTI rights, though no uniform rights standards exist within the region. Accordingly, each institution contributes to this policy area depending on their legal competence to act, and the degree of agreement over LGBTI rights.

For example, while the European Commission and the European Parliament mainly monitor LGBTI rights in potential accession and neighbourhood countries, in 2013 the European External Action Service developed specific guidelines for countries it engages with. Differences among EU member states in terms of rights recognition, however, condition the rather weak consensus on external LGBTI rights promotion. Such incoherent formulation and execution of rights policies is noticed by other countries as well.

Moreover, the EU’s LGBTI rights promotion is advanced through political conditionality in candidate states or in states that aim to receive access to its markets, visa liberalisation, or aid disbursements. My review of the EU’s annual Human Rights Reports over the past decade detected a ten-fold increase in LGBTI rights issues in third countries, which is further evidence of a heightened sensitivity to these issues.

As a result, LGBTI rights have been promoted as benchmark criteria for EU membership, as a condition to receive development aid, or in the EU’s actions in the UN’s Human Rights Council. Part of the issue is that the EU views LGBTI rights norms as constitutive for its political identity, yet they are perceived as regulative for other countries. This has led to noticeable tensions with countries in the Global South. EU delegations ‘on the ground’, however, aim at trust-building and a depoliticisation of LGBTI rights, as well as the EU’s interventionist approach on this policy.

Norm diffusion or contestation?

The most obvious case for EU LGBTI rights promotion policies can be found in countries that aim to join the Union. Here, the ‘Copenhagen criteria’ for accession specify among other conditions a respect for fundamental as well as minority rights. In the process, candidate states experience a politicisation of LGBTI rights through required policy changes and visibility measures.

After obtaining membership, some states roll back on these ‘Potemkin reforms’, which are often superficial and reversible. This has occurred, for instance, through a popular referendum aimed at revoking initially instituted equality rights in Croatia. Romania has also held a similar referendum, though without any success, while a referendum on LGBTI rights is set to be held in Hungary next year.

These reversals show that LGBTI rights promotion is contingently based on political commitments by states and the advocacy of (trans)national activists, and necessitate a domestic internalisation of tolerance norms. Similarly, the 16 countries ranging from Ukraine to Morocco included in the EU’s ‘neighbourhood’ policy, where the membership perspective remains distant, show few positive results. Despite required commitments to human rights and gender equality, reviews have shown that self-serving EU relations have often obstructed rights advances, while most democracy indicators attest to stagnation as well.

In terms of development policies, alongside different geographical preferences and colonial linkages, the primacy of establishing trade relations continues to make a coherent development policy difficult to achieve. Furthermore, conditionality, i.e. the reduction or negation of aid when set conditions are not fulfilled, is embedded in unequal power relations between the EU and the Global South. Disputes with individual recipient countries or joint EU-Africa summit clashes over the EU’s rights promotion highlight the EU’s interventionist strategy, particularly when its rights agenda is being viewed as hypocritical in face of its protectionist trade, security, and refugee policies.

In the United Nations, the EU accesses and strategically uses UN bodies and other regional organisations, though the EU’s status as a UN observer constrains its work there as well. Another EU-internal issue emanates from the fragmentation of EU representative and executive functions. For instance, in the UN the EU member states pursue their foreign policies as principals, but the EU’s diplomatic service is tasked with coordinating common policies. The UN’s Human Rights Council represents an opportunity structure for the promotion of LGBTI rights globally, yet the way sexual rights norms are visibly highlighted in often asymmetrical power relations to individual states and blocs leads to polarisation.

Rethinking rights promotion

Considerable constraints such as the volatile standing of EU LGBTI policies (within the EU), as well as rapid but reversible normative transformations (in the case of EU enlargement) remain. Externally, limited incentives and selective engagement (in the case of EU Neighbourhood Policy), post-colonial resistance and conditionality (in the case of development policy), and a politics of optics (in the case of UN rights promotion) should prompt the EU to rethink existing promotion strategies. Given the normative disparities, geopolitical pressures, and constraining limits of the EU’s LGBTI promotion thus far, a broader focus on civil pluralism and democratic consolidation would make rights promotion more sustainable, and the EU a more effective actor.

Among the EU’s institutions and member states, awareness of the need to support human rights defenders has increased over recent years. This becomes evident in the gender-rights focused policy-frameworks and the augmented budgets for external civil society, human rights and democracy promotion policies.

A more reflective intersectional multi-actor strategy could mitigate culture wars and buttress democratic pluralism abroad by taking into account country-specific socio-economic needs, and the participation of a number of non-state actors including domestic rights NGOs, educational institutions and the media. It might also include a strategic widening of the LGBTI rights discourse towards broader civic pluralism in order to build alliances and avoid a stigmatising, narrow outlook on human rights. While no ‘magic bullet’ in these complex issues exists, an extended scope of actors and activities provides a more holistic way for the EU to promote human rights.

For more information, see the author’s new book, The European Union’s International Promotion of LGBTI Rights: Promises and Pitfalls (Routledge, 2021)

Note: A version of this article appeared first at The Loop. The article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Norbu GYACHUNG on Unsplash