A popular explanation for the Eurozone crisis is that differences in wage bargaining institutions led to a major divergence in labour costs between northern and southern member states prior to the crisis. Drawing on a new study, Lucio Baccaro and Tobias Tober find that while this explanation led to wage moderation and labour market reforms being pursued in these countries following the crisis, there is little evidence competitiveness losses were caused by differences in collective bargaining institutions. Rather, differences in nominal wage growth are much better explained by patterns of domestic credit creation. They also find that wage moderation does not stimulate exports in the Eurozone, with one exception: Germany.

Ten years after the start of the Eurozone crisis, we still do not have a consensual account of what caused it. This limits our ability to learn from it and deploy the appropriate policy responses if a new crisis starts. In political economy, there are two conflicting explanations of the crisis. The first emphasises labour markets and collective bargaining institutions (see here, here, and here). The second underscores the role of international financial flows (see here, here, and here).

According to the first explanation, the Eurozone crisis was primarily caused by differences in collective bargaining institutions, which produced a stark divergence in unit labour cost trajectories between northern and southern countries. Northern countries with their ‘coordinated’ wage bargaining systems have the ability to contain nominal wage growth. However, the ‘uncoordinated’ wage bargaining systems of southern countries lack this capacity. In particular, this is due to the wage militancy of public sector unions in southern countries, which are unconstrained by competitiveness concerns.

This implies that wage inflation is higher in southern countries than in northern countries. In a single currency, competitiveness losses cannot be compensated by exchange rate devaluations, and this leads to real depreciation of the northern countries and real appreciation of the southern ones. Furthermore, different rates of inflation combined with a single interest rate set by the European Central Bank (ECB) lead to different real interest rates, boosting domestic demand in southern countries and depressing it in northern ones. This configuration of circumstances produced the current account imbalances (deficits in the south, surpluses in the north) that were a signature feature of the Eurozone in the pre-crisis period.

The proponents of the finance-centric view acknowledge the differences in competitiveness and unit labour costs between northern and southern countries but argue that they are the result of financial dynamics set in motion by the introduction of the euro. By eliminating exchange rate risks, the euro provided northern countries with an opportunity to search for higher returns by exporting their savings to southern countries. This caused an expenditure boom in southern countries, which in turn produced a deterioration of competitiveness and associated current account imbalances. An alternative version of the finance-centric view emphasises domestic credit creation stimulated by excessively low real interest rates, rather than cross-border financial inflows. However, both versions agree that collective bargaining institutions have little to do with the reasons why the southern countries lost competitiveness vis-à-vis the northern ones.

Motivated by this debate, in a recent study we estimate several statistical models to assess the respective roles of wage bargaining institutions (more or less coordinated) and credit flows (domestic or cross-border) in explaining nominal wage growth in the Eurozone between 1999 and 2014. We find that wage bargaining coordination is not statistically associated with wage growth, while credit growth (particularly domestic credit) shows a robust positive association with changes in wages. This leads us to conclude that comparative political economy has exaggerated the role of collective bargaining institutions in generating competitiveness losses in the European periphery, and that the finance-centric view of the crisis is correct in arguing that differences in nominal wage growth are much better explained by patterns of domestic credit creation.

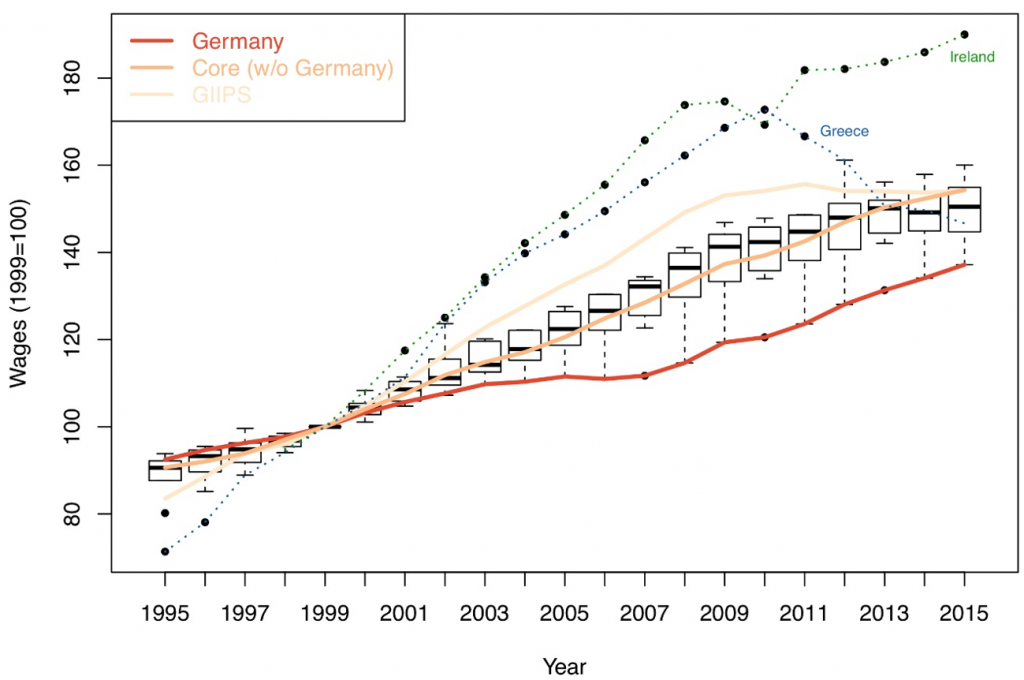

Nonetheless, we also find sharp differences in wage dynamics across Eurozone countries, although they are not clearly linked to the degrees of coordination of the wage bargaining systems. In particular, wage growth in Germany was exceptionally moderate, not only in comparison with Mediterranean countries but also with other continental countries. German nominal wages decreased by 11 percent between 1999 and 2014 relative to the average trade partner in the Eurozone. In the paper, we link wage moderation in Germany to the transition of the German economy from a wage-led growth model, in which domestic demand (financed by real wage increases) acts as a primary driver of growth, to a primarily export-led growth model.

Figure: Nominal wages in eleven members of the Eurozone (1995-2015)

Note: The figure shows how nominal wages changed in Germany, core Eurozone countries (excluding Germany), and Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain (GIIPS) from 1995 to 2014 with a value of 100 indicating the level of wages in 1999.

In a second set of analyses, we test whether wage developments in Germany and other countries affect bilateral exports in the Eurozone by estimating models in which bilateral export growth is a function of the relative (bilateral) growth of nominal wages and the relative (bilateral) growth of labour productivity. Whether unit labour costs matter for exports is another issue about which there is no consensus in the literature, in particular with regard to Germany.

A long tradition in political economy sees German exports as relying on a quality – as opposed to any cost or price – advantage. Some authors argue that the German export success has nothing to do with wage or unit labour cost moderation and is instead due to the country’s high non-price competitiveness. Others retort that Germany’s export success is the result of a ‘beggar-thy-neighbour’ strategy in which domestic wages and demand repression has engineered a real exchange rate devaluation at the expense of other countries in the Eurozone.

We find that Germany is the only country in the Eurozone for which wage moderation is a significant predictor of export growth. This effect is largely due to the very high wage cost sensitivity of sectors of medium and medium-low R&D intensity in Germany (e.g. rubber and plastic products, basic metals, textiles, food products, furniture). Our results indicate that Germany’s wage moderation vis-à-vis other Eurozone countries accounts for 27% of the growth of German exports to these Eurozone countries before the crisis (20% including the crisis years until 2014). In contrast, the contribution of German relative productivity growth was negligible (3% before the crisis). The bulk of German export growth was due to the increase of domestic demand in Eurozone partners (54% before the crisis).

These findings suggest the need to move away from black and white arguments about the role of wages in the Eurozone. On the one hand, there is no evidence that wage bargaining institutions are responsible for the loss of competitiveness of southern countries. Reforms aimed at liberalising them further are unlikely to address the competitiveness problem and will only weaken aggregate demand even further. On the other hand, wage moderation gave a non-negligible contribution to the German export success. Importantly, our analysis suggests that foreign demand is the most important determinant of export performance in almost all Eurozone countries. Thus, a coordinated demand stimulus combined with a strategy of reflation in Germany would likely help to redress imbalances and boost growth across the Eurozone.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying article in the Review of International Political Economy

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Markus Spiske on Unsplash