The concept of ‘transnationalism’ refers to the extent to which an individual’s background, interactions and practices extend beyond national borders. But do more ‘transnational’ citizens identify to a greater extent with the work of the European Union? Drawing on a new study, Anna Kyriazi and Francesco Visconti illustrate that those who display high levels of transnationalism also appear to have more engagement with EU politics.

The EU is a union of democracies, but can it be transformed into a genuine supranational democracy? Major post-Lisbon developments do not give too much reason for optimism. The handling of the Eurozone crisis, in which unelected and unaccountable institutions (the infamous ‘Troika’) dictated policies to member state governments was widely seen as trampling over popular sovereignty.

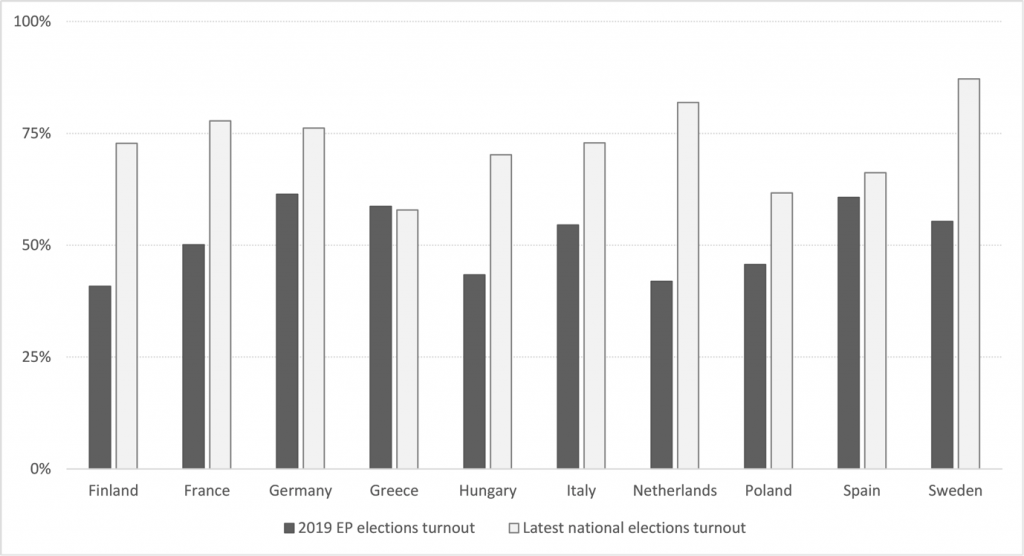

Since then, we have witnessed a systematic assault on liberal democratic institutions in several EU member states, most prominently in Hungary and Poland, which the EU has been reluctant to confront until fairly recently. Discussions over the EU’s so-called ‘democratic deficit’ tend to flare up also around European Parliament elections, held every five years, which regularly showcase a vast gap between national and European turnout levels across the Union (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Comparison between turnout levels in national and European elections in selected member states

Note: The figure shows turnout figures from the 2019 European Parliament election and the national election held immediately before the 2019 vote. The turnout data was sourced from the European Parliament (for European elections) and the Political Data Yearbook produced by the European Journal of Political Research (for national elections).

Why do people not participate more in EU politics when they have a chance to do so? One of the most common explanations is that citizens perceive the EU as being too technocratic and too distant. Citizens do not understand how the EU works, they do not identify with it, and they are therefore uninterested in EU affairs.

This is in line with a general tendency, documented by studies on local democracy and ethno-regionalism, for people to get more involved in politics as the political unit becomes smaller. In one intriguing study, Mabel Berezin and Juan Díez Medrano also found that support for the EU depended quite literally on physical distance, i.e., how close, or far away from Brussels (the EU’s administrative and political centre) individuals lived.

This suggests there is a perceptual and affective barrier to EU-level political participation. But are there ways to overcome this barrier? In a recent study, we argue that cross-border interconnectedness and transnational social exchange is an avenue for EU politics to become more supranational. The key explanatory variable we consider is ‘individual transnationalism’, which refers to “the extent to which individuals are involved in cross-border interaction and mobility”.

This includes physical mobility and contacts, but people need not migrate for their realm to become ‘transnationalised’ – a term, borrowed from a ground-breaking study by Theresa Kuhn, which refers to any form of social exchange and cultural competence that spans national borders. This can be reading books in a foreign language or having colleagues who are from another EU member state, among others. As Ulrich Beck wrote two decades ago, “‘transnational’ implies that forms of life and actions emerge whose inner logic comes from the inventiveness with which people create and maintain social lifeworlds and action contexts where distance is not a factor”.

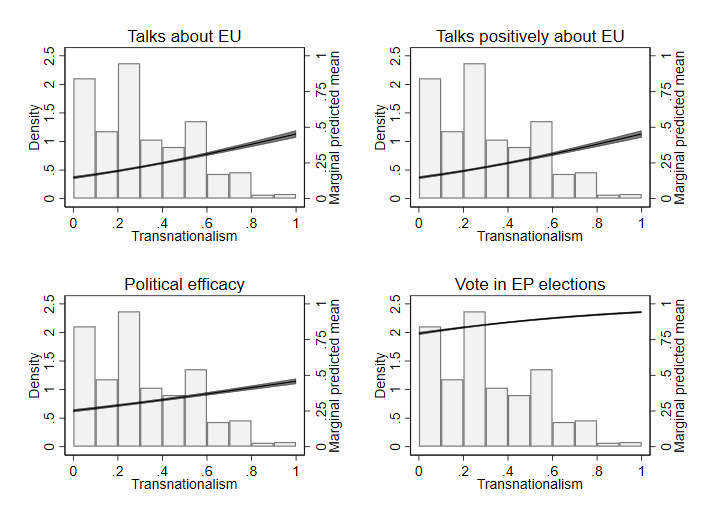

We examined various forms of European political participation, from voting in European Parliament elections, to supranational political efficacy, to simply talking (positively) about the EU. We argue that transnational backgrounds, practices, and competences transform the way people perceive the European political space: they alert them to the supranational scope of the political process; they make them more knowledgeable about European politics; and they increase the degree to which they care about fellow European citizens.

Self-interest is also part of this process. Transnational individuals are among the so-called ‘winners’ of globalisation and its European variant, EU integration, and therefore they may perceive that the stakes of European politics are higher for them as compared to less transnational individuals. The results of our analyses, which are based on survey data collected in ten EU countries after the 2019 EP elections, consistently show that the more transnational an individual is, the more they are likely to engage in such activities (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Transnationalism and EU politicisation

Note: The figure shows the marginal effects of transnationalism on components of EU politicisation using data from the ‘Reconciling Economic and Social Europe: The Role of Values, Ideas and Politics’ (REScEU) project. For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper.

As cross-border social exchange intensifies in the integrating EU, this also means that people will become more and more involved in EU-level politics. In the long run, this could partly correct the EU’s democratic shortcomings and increase its legitimacy. However, this comes with some drawbacks, too.

On the one hand, transnationalism is not evenly distributed across societies: people from a higher social class, in higher status occupations, and with higher educational attainment tend to be more transnational as well as more involved in politics. In other words, transnationalism boosts the participation of those who are already among the most resourceful and the most interested in politics.

On the other hand, the positive influence of transnationalism on participation in supranational politics may be accompanied by a relative detachment from national-level politics. That is, the participation of transnational citizens in supranational politics is not complementary to their participation in national politics, but rather is something that is in competition with their engagement with national-level politics.

Nevertheless, the roads toward more robust forms of democratic inclusion at the EU level are many, and cross-border interconnectedness is only one of them. Proposals such as the currently on-going Conference on the Future of Europe, or the European Citizens’ Initiative, among many others, also have an important role to play in boosting political participation and securing popular consent for EU integration.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Electoral Studies

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: CC-BY-4.0: © European Union 2021 – Source: EP