Populist parties typically voice strong criticism of the establishment, but what happens when these parties join national governments? Drawing on a new study, Pedro Riera and Marco Pastor illustrate that populist parties are vulnerable to losing support when they become junior members of a governing coalition. These parties tend to lose more votes when they are ideologically radical, when the coalition they join is ideologically homogenous, and when the coalition holds a majority in parliament.

Populist parties have risen to prominence across advanced democracies in recent decades, especially in Europe, where proportional electoral systems give them better opportunities to obtain representation. In some cases, these parties have fizzled out after a few electoral cycles. In most cases, though, populist newcomers have succeeded in joining the club of parliamentary insiders and have even risen to the highest levels of office, as with Fidesz in Hungary, Syriza in Greece, and Law and Justice in Poland.

In response to this populist challenge, mainstream parties have been increasingly confronted with the following dilemma: either to create a cordon sanitaire by rejecting any association with populist actors, or to invite these parties into government by forming a tainted coalition.

On the one hand, established parties in some countries have used the cordon sanitaire strategy, like in Sweden with the Sweden Democrats, in Germany with the Alternative for Germany, in the Netherlands with the Party for Freedom, and in France with the National Rally (formerly, National Front). On the other hand, some populist parties have been invited into coalition governments, such as the Freedom Party in Austria and the League (formerly Northern League) in Italy, or have established confidence and supply arrangements, like the Danish People’s Party.

Proponents of the cordon sanitaire approach have argued that marginalising populist parties hurts them because it makes them less appealing to strategic voters. It also signals to moderate voters that they are ‘beyond the pale’ and makes it harder for them to attract competent and likeable candidates. Moreover, inviting populists into government gives them greater legitimacy and visibility and can contribute to ideological polarisation.

However, as proponents of the tainted coalition strategy have noted, ostracising populists also risks galvanising their support in subsequent elections. Instead, inviting them into coalition governments can dilute their populist appeal. This approach can stifle their growth because of the ‘costs of governing’ – the principle that political parties lose electoral support when they enter office.

In a recent study, we look at how populist parties are affected at the ballot box after joining coalition governments as junior members. Using a comprehensive dataset compiled by Heike Klüver and Jae-Jae Spoon, we analyse the vote shares of 266 parties that either joined coalitions as junior partners or stayed in opposition across 196 elections in 28 European countries between 1972 and 2017.

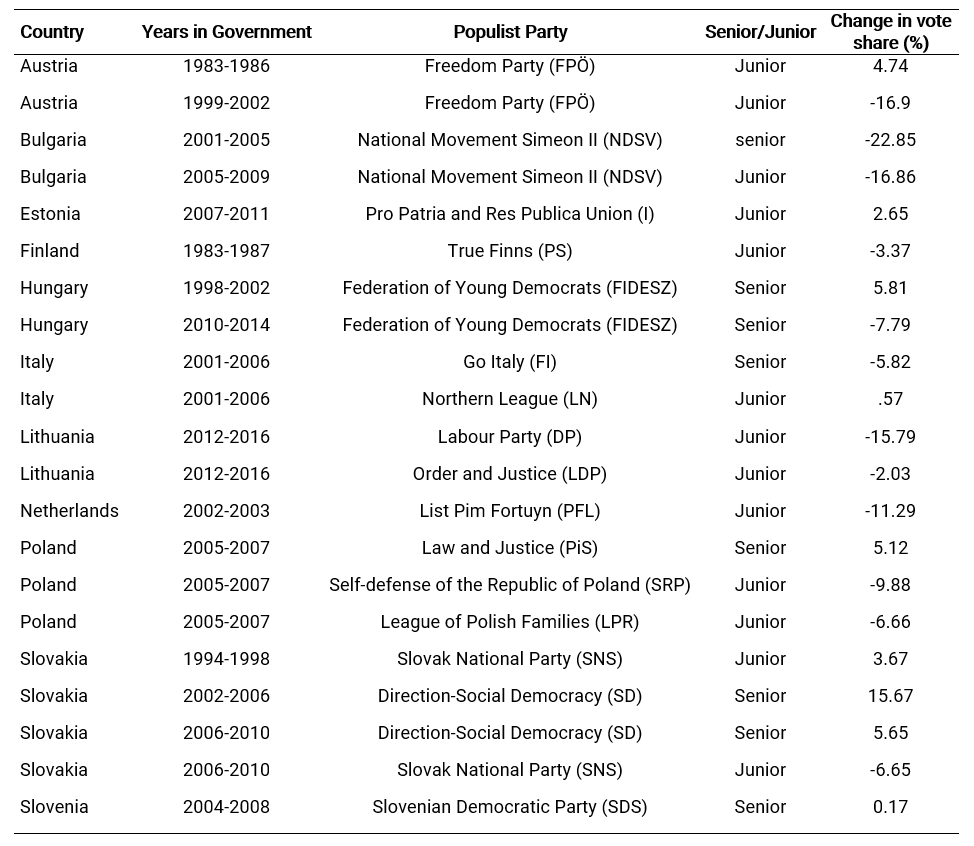

Parties are classified as populist or non-populist based on the Popu-List dataset. The regression models we estimate control for vote share in the previous election, share of seats in parliament, ideological radicalism and intra-cabinet conflict. Table 1 summarises the populist parties in the sample that joined coalition governments.

Table 1: Governments including populist parties in sampled countries (1972-2017)

Note: Compiled by the authors.

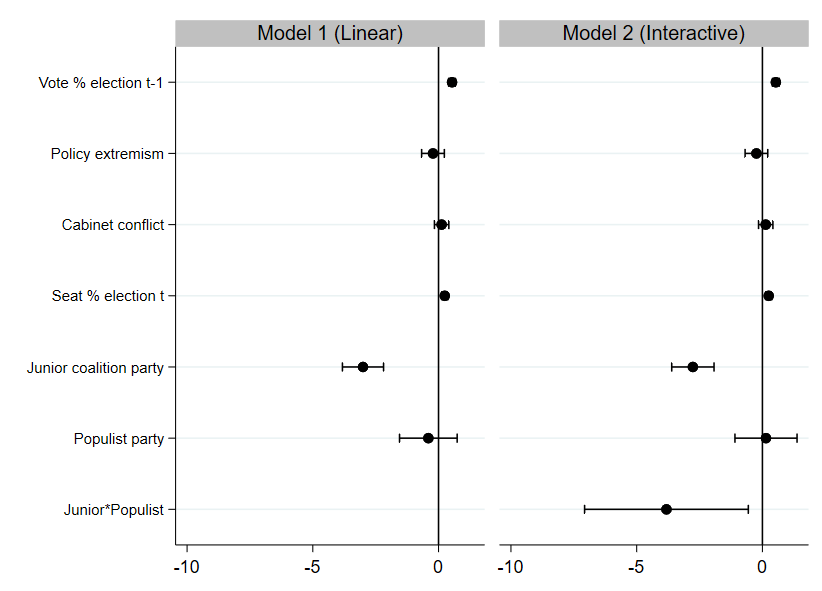

The first analysis, summarised in Figure 1, shows that parties that join coalitions as junior partners tend to lose 3.2 percentage points in their vote share at the next election. This is likely because junior partners get fewer benefits from office, have less control over the agenda, and have less personnel capacity to manage both governmental and partisan affairs. However, the results show that junior partners lose 7.1 percentage points when they are also populist parties. This suggests that joining coalition governments tends to be particularly damaging to populists.

Figure 1: Determinants of the electoral performance of junior coalition members and their opposition parties when they are populist

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Party Politics.

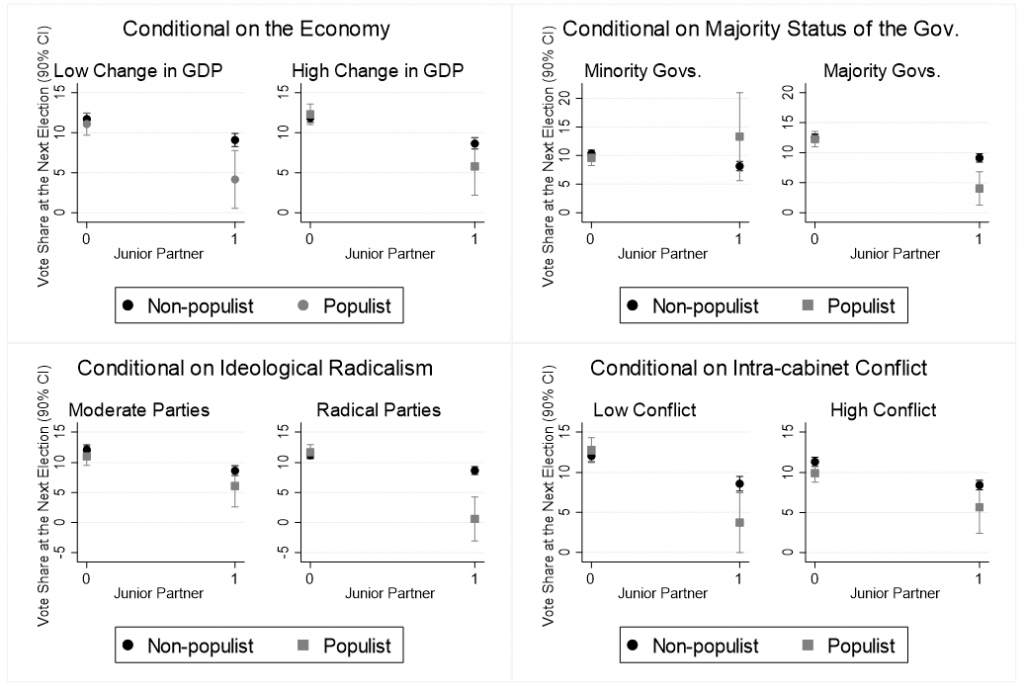

In the second analysis, summarised by Figure 2, we examine four possible explanations for why junior partners lose even more votes when they are populist: economic mismanagement, lack of antagonism against the establishment, ideological backlash, and loss of populist ethos. These hypotheses are tested by splitting the sample by the median of different proxies and comparing the costs of governing across different types of governments.

Figure 2: The cost of governing for populist parties

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Party Politics.

The first explanation we test is that populists lose votes when they enter coalitions as junior partners because the economy performs worse, and voters blame them for their economic mismanagement. Parties tend to lose votes when the economy does poorly, even for multi-party governments, albeit to a lesser extent. However, populist parties do not seem to be affected by the state of the economy. When we compare situations of low and high GDP change over the term (see upper-left panel of Figure 2), we find that the effect of entering a coalition government for populist parties is practically the same in both situations.

The second explanation we test is that populists lose additional electoral support when they join governments with parliamentary majorities because it becomes harder for them to portray themselves as fighting a corrupt and powerful elite when their government has unconstrained power. Since grievance and the feeling of being muzzled are essential, when they form part of a minority government, they can still claim to be oppressed by the parliamentary majority that opposes their coalition. Indeed, we find that when the cabinet holds more than 50% of the seats in parliament, voters are more willing to defect from a governing populist party, as the cost of governing for populist parties is 4.9 percentage points higher in majority governments (see upper-right panel of Figure 2).

The third explanation we test is that populist junior partners lose more votes because of their ideological radicalism and their subsequent higher vulnerability to disappointing their supporters once they enter government. The results support this explanation, showing that the cost of governing for populists that are ideologically radical increase to 8.6 percentage points, three times bigger than for non-populist radical parties.

The final explanation we test is that entering government can erode the populist ethos that is quintessential for this type of party. Parties can use intra-cabinet conflict to differentiate themselves from other coalition members and signal their disagreements to voters. For populists, this can be the easiest and most effective way to put their anti-establishment credibility on full display. Therefore, populists in coalition governments that fail to cause some trouble may disillusion their supporters more quickly.

As expected, the cost of governing for populist parties is much higher when there is a low level of intra-cabinet conflict. When this happens, the anti-establishment stances of the populist parties become blurred, and they lose on average 5.6 percentage points in the next election. In contrast, the cost of governing does not increase for populist parties when the cabinets they belong to present high ideological heterogeneity.

In sum, populist parties suffer higher costs of governing when they join coalitions as junior partners, and three moderating variables help us explain why. Junior populists tend to lose more votes when they are ideologically radical, and when the coalitions they join are ideologically homogenous and hold a majority in parliament. However, economic conditions do not seem to play an important role.

The implications of these findings are straightforward: populists lose support when they are bogged down by majority coalitions with senior partners that share similar ideologies. Therefore, mainstream parties that hope to hinder populist challengers ought to invite them to large coalitions that are ideologically homogeneous. Meanwhile, populist parties that aim to grow should refrain from joining these coalitions. And if that proves untenable, they should strive to join minority coalitions that are ideologically heterogeneous.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Party Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council