Why was support for Brexit so widely divergent across the UK? Drawing on a new study, José Javier Olivas Osuna, Max Kiefel and Kira Gartzou-Katsouyanni illustrate that while a variety of economic and cultural explanations for the result have been put forward, these processes were shaped at the local level. They find that citizens with similar socio-demographic profiles adopted very different attitudes toward Brexit depending on the local context in which they lived.

The 2016 Brexit referendum exposed and arguably exacerbated significant levels of political discontent and polarisation in Britain. The referendum also unveiled stark geographic discrepancies in terms of citizens’ views across the UK. The Leave vote ranged from just 21.4% and 21.5% in Lambeth and Hackney to 73.3% and 75.6% in South Holland and Boston.

In a recent study, we sought to find out more about these disparities by investigating five cases – Barnet, Ceredigion, Mansfield, Pendle and Southampton. During our research, we engaged with local stakeholders such as local politicians, business owners, civil society activists and journalists within these areas to validate our findings. Our research provides some important insights about the local factors that helped shape the result.

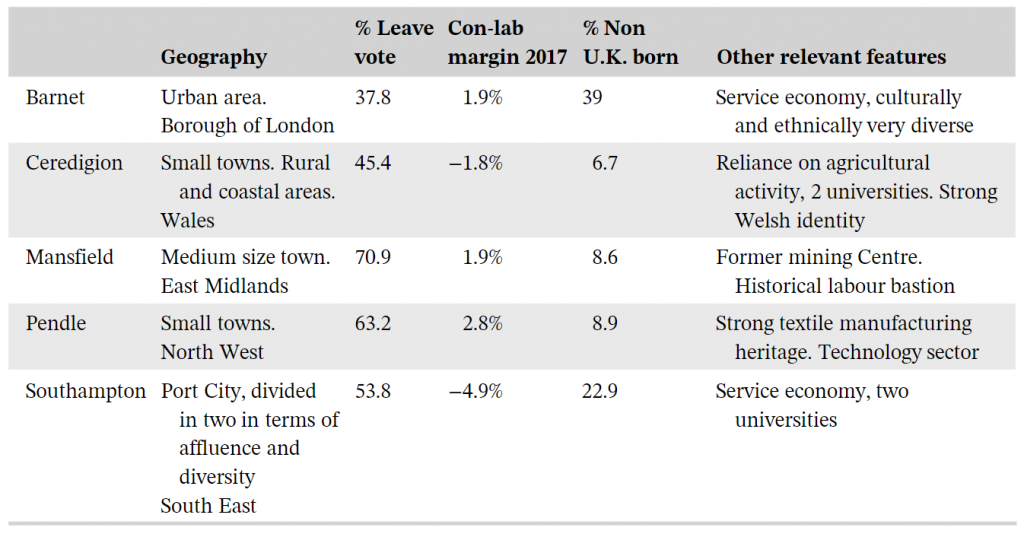

Table 1: Key characteristics of the case studies

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on ONS and Electoral Commission data.

Britain offers an archetypal example of the way in which discontent and a lack of trust in politics have spread across the European Union. It is impossible to fully explain the outcome of the Brexit referendum without considering this loss of trust. Over the last fifty years, the UK has seen a steady rise in political discontent and an accompanying decline in support for politics. The global financial crisis and subsequent austerity policies contributed to this loss of political trust, and by 2016, only 26% of low-income Brits trusted the government.

It is well established that populist leaders can fuel and instrumentalise a lack of public confidence and socio-economic and political crises to advance their agendas. Crises are considered to be a window of opportunity in this sense as they erode trust in representative institutions, fuel grievances, and serve as justification for radical measures. Brexit was no exception to this. UKIP and other members of the Leave campaign actively promoted distrust in the political establishment and the EU in an attempt to establish an antagonistic dynamic pitting the ‘people’ against the ‘elite’.

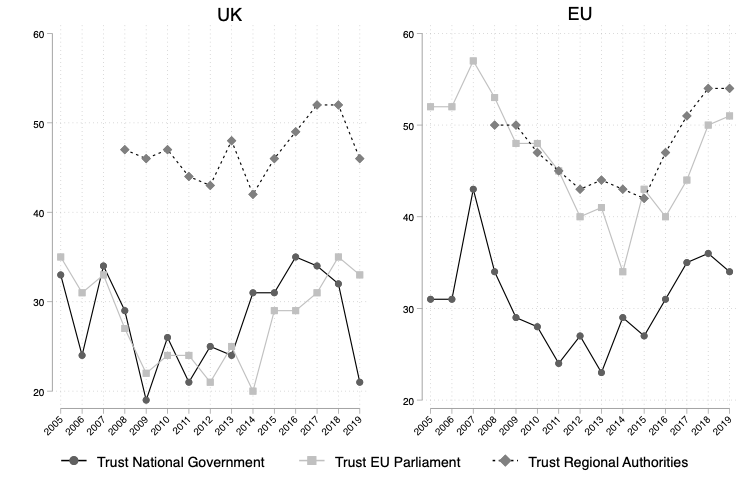

Figure 1: Trust in national governments, the European Parliament, and regional authorities in the UK and the rest of the EU

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on Eurostat data.

Several economic and cultural factors have been identified as sources of political discontent and support for Leave during the 2016 referendum. Some authors have suggested the result stemmed from frustration among the ‘losers’ from globalisation and the neoliberal growth model. Others have pointed to English nationalism and negative attitudes toward migration as the key cultural drivers of Euroscepticism.

However, when analysed from a local perspective, it becomes clear that these competing cultural and economic causes of discontent are deeply intertwined. One of the key findings from our research is that the sense of political disempowerment, neglect and negative attitudes vis-à-vis migration that many Leave voters expressed were ingrained in and reinforced by locally specific socio-economic and political trajectories.

Local structural factors and the erosion of political trust

Our fieldwork indicated that a strong sense of disempowerment and loss of sovereignty were the main sources of political dissatisfaction. Interviewees claimed these grievances transcended individuals and were attributed to the entire community. Responses suggested that the neglect of post-industrial areas was attributed in part to a lack of political attention.

One respondent, for instance, indicated that ‘Mansfield as a town, like many others in Britain, has been overlooked’, while Ben Bradley, the MP for Mansfield, described the town as being ‘left behind in terms of the government caring about things outside of London’. Another respondent from Nelson, a town located in the Borough of Pendle, expressed similar views, noting that cities ‘are grabbing everything’, while ’towns are left behind’ and ‘people feel abandoned by the elites’.

These localised feelings of neglect and disempowerment were ripe for mobilisation via the Leave campaign’s call to ‘take back control’ and regain sovereignty. In all of the Leave areas we studied, including Mansfield, Pendle and Southampton, migration was widely acknowledged by interviewees as the ‘main issue’ that local Leave campaigns focused on. Eastern European migrants were often specifically identified as likely to take low-skilled and low-paid jobs.

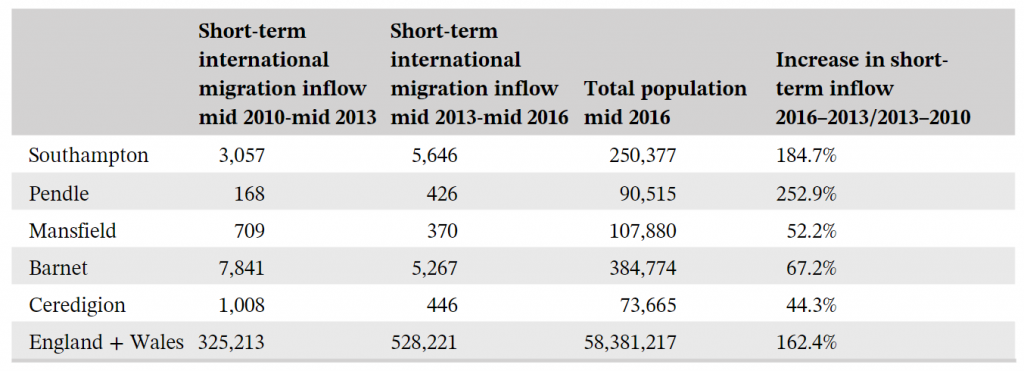

It is important to note, as Table 2 shows, that these subjective perceptions do not necessarily align with objective realities. For example, wage stagnation in the UK has been found to be associated with the financial crisis and not migration. Our findings appear to support the conclusion that anti-migrant sentiments are not correlated with the size of the migrant population in a specific area and only partially with short-term increases in migration.

Table 2: Short-term international migration inflows

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on ONS (2018) data.

Negative attitudes toward non-EU citizens and British ethnic minorities were also associated with Brexit. Migrants and non-white British groups were portrayed as being insufficiently integrated with the rest of the local community. The Leave campaign also sought to portray national and local identities as being under threat using anti-immigration discourses. Specific local issues related to migrants and British minorities were important in articulating a latent demand for this kind of defensive argument.

Additionally, local economic problems interacted with the above-mentioned sources of discontent and helped shape collective interpretations and choices during the referendum. Regeneration policies had failed in many towns, particularly in the North of England, which created visible imbalances. In areas with a declining or stagnating economy, like Mansfield and Pendle, residents were increasingly concerned with a perceived lack of opportunities and government neglect. Decreasing wages, scarcity of job opportunities, and strain on public services, which Leave campaigners attributed to immigrants and EU membership, were found to be largely caused by long-term economic issues in the area.

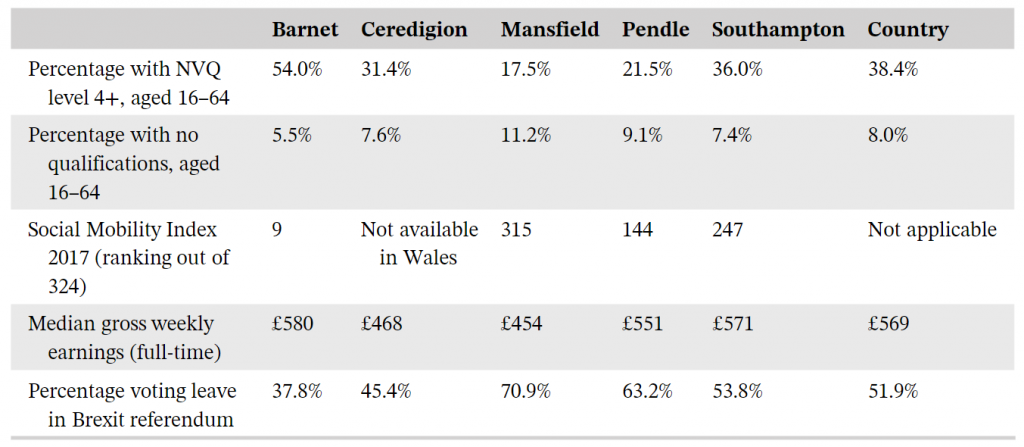

Table 3: Education, social mobility and the Leave vote

Source: Annual Population Survey (APS), Social Mobility Commission (2017), and Electoral Commission (2017b). Social Mobility Index (Nomis, 2018a; 2018b).

Geographic features and a lack of infrastructure, which residents mentioned as a strong competitive handicap, were also sources of discontent. Mansfield was described as, ‘a long way off the motorway (…) getting in and out is a nightmare’, while Pendle was repeatedly described as ‘the cul-de-sac’ of Lancashire. The perception that these local authorities were removed, economically and culturally, from the rest of the country appears to have been a strong factor in fostering feelings of being ‘left-behind’. This contrasts with places like Barnet, which are embedded in large urban areas and close to economic and political power hubs, where the majority voted Remain.

Pride and economic change

Distrust of political elites and the EU’s institutions in the areas we studied can be explained by the interplay of economics and cultural grievances within specific local contexts. These contexts filtered and shaped individual and collective interpretations of the competing Brexit campaign ‘top-down’ narratives, overshadowing expert data and ‘neutral information’.

Citizens interpret facts in relation to their life experiences and immediate social context. Their political understanding is constructed by common-sense assumptions and routinised practices. The slogans and simplistic arguments disseminated nation-wide by the Leave campaign and reproduced by the tabloid press gradually became internalised and routinised in some communities, combined with bottom-up interpretations of specific local cultural and socio-economic issues.

Pro-Brexit narratives, which became predominant in areas such as Mansfield and Pendle, contributed to the entrenched views that hindered meaningful discussion post-referendum. We found people in these areas often had a shared sense of pride in ‘sticking to their decision’ and an anti-elite sentiment built on the principle that ‘you cannot tell the people that they were wrong voting Leave (…) [or] what to think’. Several participants in our study showed reluctance to question certain assumptions and others were reticent to reveal their support for Remain in public or on the record. This seems to reflect processes of ‘informational coercion’ and certain levels of cognitive dissonance.

The strength of these narratives, combined with the weakness of local Remain campaigns, partially explains why many people in areas like Mansfield and Pendle chose to support Leave. According to some predictions, these areas were likely to be negatively impacted by Brexit, yet many voters still chose to back Leave and were not receptive to arguments rooted in expertise or data that cast doubt on some of the claims made against the EU.

Selective use of references to tangible issues in the community also strengthened the resonance of Leave discourses. This included issues such as the transformation of local economic activity, changes in the local landscape, the decay of infrastructure, grievances with neighbouring cities, and increased strain on the healthcare system and education.

These discourses offered a view of the British people as being betrayed by metropolitan and European elites. Brexit was framed as an opportunity for change and a way to restore a sense of local pride and ownership in the community – something that had been eroded through economic transformations linked to globalisation. Nostalgia, resilience and optimism were common ingredients combined to dismiss the predicted risks associated with Brexit or justify the process as a ‘necessary evil’.

Ultimately, political trust influenced voting behaviour, but it did not act purely as an exogenous variable. This ‘revenge of the places that don’t matter’ can be considered part of a process of ‘crisis building’ or ‘manufacturing’. Political trust was purposely undermined by the Leave campaign to trigger a protest vote against the British and EU establishment.

The radical solution they offered was theoretically intended to shield ordinary people from unwanted changes at the identity level while truncating a perceived path of relative economic decline and political disempowerment. It remains to be seen if pro-Brexit politicians succeed in addressing the sources of discontent that led people to vote Leave, but there is no doubt they succeeded in delivering a crisis.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in Governance

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Ian Cylkowski on Unsplash

Remarkable that the authors were not able to uncover the democratic deficit created by Devolution as a driver for brexit.

In 1998, a minority of the uk population in the ‘celtic’ nation were given additional rights and privileges over and above the rights and privileges given to british citizens in general; this policy is called ‘Devolution’. The primary argument behind Devolution is that it gives people in the ‘celtic’ nation greater control over their own lives. Devolution rights and privileges have not been provided to English people, who only have rights as British citizens.

During the Brexit process, leave voting people consistently expressed the desire for more control over their lives. The demography of the leave vote is higher in England than it is in the ‘celtic’ nation. It seems obvious that the inequality of Devolution is a significant driver of the leave vote. However, the authors have chosen not to ‘discover’ this inconvenient truth and have instead attempted to write off this inequality by implying that those disadvantaged by the racial inequality of Devolution are themselves racists.

Nul points. Must try harder

If you look at data from surveys like BSA, SSA and so on then Scotland has been more Europhile than England since at least the early 1990s. Just claiming Scottish devolution is the root cause of English Euroscepticism without providing any evidence beyond correlation isn’t much of an argument. All you’re really doing here is taking an issue you happen to care about and projecting it onto the rest of the electorate.

I am not ‘just’ presenting a correlation. The whole ethos of devolution is to empower those privileged by it with greater control; English citizens are denied these privileges; leave voters explicitly cited the quest for more control. How much more clear could it be and yet no mention of devolution in this article. Par for the course. Scapegoat the disadvantaged as usual.The eu over-represents small parties and ‘celtic’ nations in particular; naturally those privileged ‘celts’ reciprocate while English people resent the racial inequality.

Brexit is primarily a domestic rebalancing of power within the british isles. English people have a right ti be treated equally and fairly

I have little doubt that your point is valid, though it doesn’t fully explain why Wales voted to Leave, albeit by a rather smaller margin than England. What does need explaining though is how the Leave campaign was so easily able to persuade the electorate that their strong sense of disempowerment and loss of sovereignty, along with the neglect of post-industrial areas, had anything at all to do with the EU rather than to failures by successive UK governments. In fact it seems highly unlikely that the UK government, now on its own, will provide anywhere near the same level of funding for deprived areas of the UK as was previously available from the EU. The remedies for the unquestionably justified grievances were at all times in the hands of the UK, and there were no relevant EU restrictions on the UK preventing it from doing all that could be to modernise the poorer areas.

Excellent points solchap. One could point to the steady drip-drip-drip of negative coverage with regard to the EU that has existed since we joined in the early ’70s. Strikes me that many folks did not have much of a sense of why the UK was part of the EU beyond a vague notion of the single market. I recall some mention a long time ago of a school curriculum that would include discussion of what the EU is, how it works, the pros and the cons for the UK etc etc. But that was shot down pretty quickly, as if speaking about it in school lent the EU a legitimacy it did not deserve. Given the lack of information about the benefits of EU membership (the negatives being well-covered in the media) it doesn’t surprise me that areas that benefitted economically from EU funding voted against the EU. Any ongoing frustration, as you note, should be with the failures of successive UK governments. The bitter irony is, and as the authors point out, there’s plenty of areas where people feel forgotten and marginalised, and leaving the EU won’t improve that situation at all. So, instead of perhaps seeing an improvement in people’s attitudes in these areas with regard to frustration with politics, now that we are no longer part of the EU we are likely to see even more disappointment and confusion. Time will tell. The general point being made about devolution requires more evidence to convince me – I daresay if we went out on the streets and asked people about the ‘West Lothian Question’ they wouldn’t have a clue what we were going on about. I think it’s fairer to say, as has been noted, that people who voted leave were more concerned about the idea of an interfering EU than they were about Scots having more rights.

Interesting piece of research highlighting the importance of local contexts in shaping both cultural and economic concerns.

Completely agree with Harry L’s comments. Feels like Peter Davidson was reading a different article entirely – correlation is not causation, and he provides no empirical support for his critique unless you count the phrase “it seems obvious…”The criticism that the authors imply those looking to devolution as an explanation for devolution are racists is ridiculous. Where did that come from?

Very interesting investigation, thanks. It is perhaps a shame the article is sometimes written from a standpoint of ‘these voters obviously got it wrong, the authors know what’s actually best’. A bit more objectivity would have been helpful – there was surely some rational self interest at work for many working class brexit voters – perhaps just as much as there was for middle class remainers.

(continued from above) eg limiting mass immigration might be expected to reduce competition and increase pay for semi/unskilled jobs, it may also reduce pressures on public services eg council housing. Recovering sovereignty could enable increased political influence for marginalized communities, including increasing pressure on gov’t to ‘level-up’. These look like rational, perhaps evidence based reasons for Mansfield and other such communities to vote Brexit some/ all of which have been borne out.