Millions of Ukrainian citizens have fled to other European countries since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war. However, there remains much that is unknown about the needs of Ukrainian refugees and their views on the support they have received. Steffen Pötzschke, Bernd Weiß, Anna Hebel, Joachim Piepenburg and Oleksandra Popek present preliminary findings from a new online survey that sheds light on the situation faced by those who have arrived in Germany and Poland.

As of 8 May, an estimated 5.9 million Ukrainians have fled their country to escape the Russia-Ukraine war. In response, most European countries have opened their borders and assisted people to the best of their abilities. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Poland alone has taken in more than 3.2 million refugees from Ukraine since late February. In Germany, the Federal Police reported that 402,651 Ukrainian refugees had arrived in the country by 4 May.

To organise and coordinate relief activities and related policies, actors such as government agencies, supranational organisations, and non-governmental organisations need timely information on these refugees. While surveys can be utilised to provide such information, the recruitment of refugees is difficult in a situation such as this as the population of interest is in constant flux and might not be reached by established sampling techniques.

Against this background, we conducted a web survey of Ukrainian refugees* in Germany and Poland, using targeted advertisements on Facebook and Instagram for participant recruitment during the second half of April. Our study was conducted in the Ukrainian language and targeted adults (18 years and older) in both countries who had left Ukraine since the beginning of 2022.

While we believe that sampling through social networking sites is an appropriate method for gathering crucial information in the absence of other sampling frames, it is necessary to highlight the limitations of this non-probabilistic sampling approach. Most importantly, descriptive results obtained by any non-probability method can usually not be generalised to a larger group of interest.

Consequently, we can only report findings on participants in our survey without claiming that these might apply to Ukrainian refugees in general. However, since more reliable sampling strategies are largely unavailable at short notice, surveys such as ours can at least provide some information where none would otherwise be available. More importantly, our research can point at issues, questions, and problems that warrant further systematic investigation.

Demographic characteristics of the sample

Between 15 April and 1 May, a total of 1,271 adults participated in our survey. In the following, we focus on a subsample of 1,194 respondents for whom we can provide the below-mentioned information. Slightly more than half of them (666 – 56 per cent of the total) were in Germany, while 44 per cent (528) were located in Poland at the time of their participation. All but one of these individuals were either born in Ukraine or held Ukrainian citizenship.

It has previously been reported by UN agencies and news outlets that women strongly outnumber men amongst Ukrainian refugees in many host countries; consequently, it is unsurprising that an overwhelming majority of 88 per cent of respondents in our study were female. This gender distribution amongst Ukrainian refugees is at least partially due to the fact that men of Ukrainian nationality between 18 and 60 years of age are currently prohibited from leaving the country.

Regarding refugees’ social support and psychological well-being, as well as their needs in terms of housing and geographic placement, the question of whether they migrated alone or in larger groups is relevant. Amongst our respondents, only a minority (23 per cent) left Ukraine alone. In contrast, more than three-quarters left the country accompanied by family members, friends, or acquaintances they had already known before embarking on their journey. Six out of ten respondents left Ukraine with groups that included at least one child under the age of 18. More than a fifth of participants were accompanied exclusively by minors, i.e., without other adults in the group.

Time since arrival, registration, and housing

Using social networking sites, we were able to survey respondents shortly after they had arrived in Germany or Poland. As mentioned above, all respondents included in this analysis had left Ukraine since 1 January. Unfortunately, 26 per cent did not provide a valid and complete date for when they entered Germany or Poland. However, of the remaining respondents (878) four per cent came within less than 24 hours before taking the survey, ten per cent resided at least one day but less than four weeks in either country, and 69 per cent did so for four to just under eight weeks.

With respect to official statistics and the ability to receive government aid it is, of course, also relevant to know whether refugees register in a timely manner with authorities. Regarding individuals who fled Ukraine, this is all the more important as they can legally enter Schengen countries without the need for additional documentation.

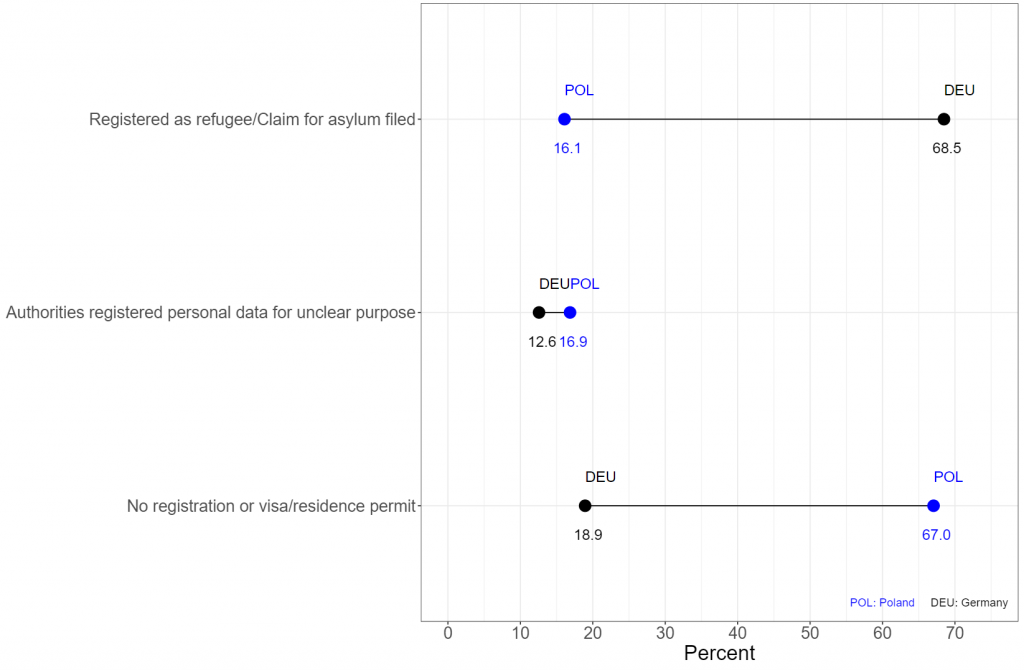

Twelve participants held either German or Polish citizenship. Clear differences regarding official registration are visible between respondents of the remaining sample in the two surveyed countries (see Figure 1). While almost 70 per cent of those interviewed in Germany had at least been registered as refugees or even filed official claims for asylum, the same held true for only 16 per cent of respondents in Poland. However, 67 per cent of respondents in the latter country specified that they had not been registered by or with the authorities at all. In comparison, this was the case for only 19 per cent of the participants in Germany.

Figure 1: Registration status with governmental authorities of refugees by host country

Source: Compiled by the authors.

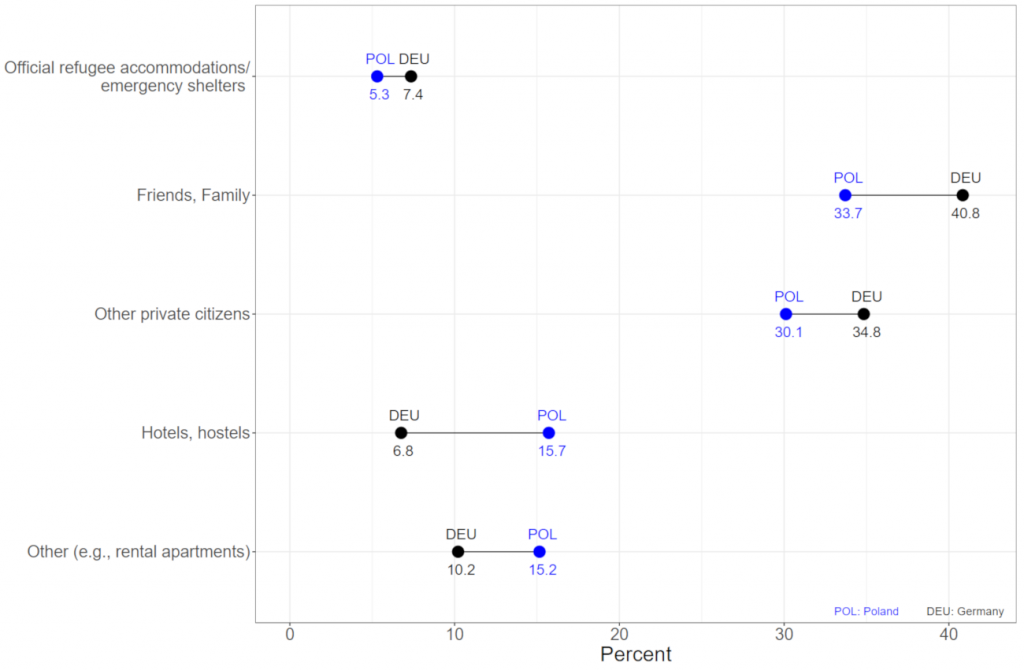

Another important question is refugee housing. From an individual perspective, the placement in government-run facilities might, on the one hand, allow easier access to information and direct assistance. On the other hand, lodging with friends, family, or other (German or Polish) citizens might provide social contact and access to informal networks.

From an institutional perspective, this issue is of interest as it might be seen as an indicator of the level to which governments need and are able to provide refugees with housing themselves or are reliant on private citizens to do so. Furthermore, the willingness of millions of private European citizens in host countries to open their flats and houses to Ukrainian refugees is certainly a strong sign of solidarity with those in need. However, it is also clear that private households cannot care for such guests indefinitely, nor should refugees permanently have to forgo the privacy of individual housing.

Figure 2: Housing of refugees by host country

Source: Compiled by the authors.

As Figure 2 shows, only a few of the respondents in our study were actually housed in official refugee accommodations or corresponding emergency shelters at the time of the survey. While a clear majority stayed in the homes of private individuals in both countries, the specific percentages of respondents who stayed either with friends and family or with other private citizens were somewhat higher in Germany than in Poland. In contrast, significantly more of those surveyed in Poland stayed in hotels or hostels than was the case in Germany.

Assessment of received assistance

Finally, our survey also asked respondents to rate their satisfaction with the help Germany and Poland had thus far provided on a scale from one (very unsatisfied) to seven (very satisfied). We found, on average, a high level of satisfaction about the help respondents had personally received, with only minor differences between the two countries. Respondents in Poland were slightly more content (an average score of 6.0) than those in Germany (an average score of 5.7).

However, differences were apparent in the assessment of the help Ukraine as a whole had received from Germany and Poland since the beginning of the war. Survey respondents in Poland were overall very satisfied with the performance of the Polish government and state, even more so – to a slight degree – than with the help they had personally received (an average score of 6.4). In Germany, on the other hand, the support provided by the state to Ukraine was rated less positively, with an average value of 4.3.

* The authors would like to make clear this article uses the term “refugee” in a broad sense that is not limited to its legal meaning.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: UN Women Europe and Central Asia (CC BY-NC 2.0)