Policymakers frequently use education as a welfare policy instrument. But can these policies have unintended consequences? Christos Genakos and Eleni Kyrkopoulou present findings from a case study in Greece where a social policy aimed at helping poor families and alleviating inequality has had a counterproductive effect by lowering the academic performance of other students.

Education, with its multifaceted role, is a key social policy instrument that has been used to address inequality of opportunities and the structure of society by mixing students from various socioeconomic backgrounds in public schools, by allowing school choice, or through specific policies such as affirmative action in university admissions or desegregation programmes in schools. Such policies are strongly predicated upon the assumption of significant positive peer effects. We analyse one such example, where university access is used as a (non-cash transfer) social policy to help large and financially constrained families.

To gain university entry, students in Greece participate in a national examination system. Based on their grades and their declared preferences, students get allocated to different universities and departments. After this allocation, the Ministry of Education operates a special transfer system, as part of its social policy, to assist large and financially constrained families. This policy gives students from such families who have gained entry to a university far from home the opportunity to ‘transfer’ to a similar subject university department in (or near) their hometown, giving them the opportunity to reduce living costs.

However, if transferred students are of lower academic quality than the ‘receiving’ students who were already in this department, this raises the possibility that the policy could have a negative effect on their receiving peers. Various changes in the relevant legislation have resulted in a large, quasi-random, variability in the number of transferred students over time, creating serious problems both at the leaving and at the receiving departments.

We present the first systematic examination of transferred university students’ impact on the academic performance of students in receiving departments. Our study belongs to the ‘exogenous movement of people’ category of natural experiments. Similar studies have previously been done to assess the impact of a desegregation programme that sends students from Boston schools to more affluent suburbs, and the effect on schools receiving evacuees following Hurricane Katrina.

We look at a university environment rather than schools, where the empirical literature reports mixed evidence on peer effects so far. As Alfredo Paloyo highlights in a recent review: “at the university level, peer effects are modest if non-existent for academic performance”.

We constructed a novel dataset from the best undergraduate economics department in Greece by linking students’ personal and pre-university academic performance characteristics with their entire university academic performance record until graduation. Looking at the academic performance of transferred students before going to university, it is clear that both their school grades and their performance on the standardised national examinations are significantly lower than those of their peers in receiving departments.

But the key question we wanted to analyse is whether the presence and increasing number of transferred students exerts any influence on the academic performance of students in receiving departments. On the one hand, if the number of transferred students in a given class is small, one could hypothesise that their impact during lectures would be limited. Also, assuming that transferred students are the worst performers in exams, this might even help students in receiving departments get higher grades, if some form of grade normalisation is used.

On the other hand, one could envisage that these large differences in academic capabilities could have a negative impact on the students in receiving departments. Transferred students may find it difficult to follow the pace in classes, or may delay or distract the lecturers with questions, hence making classes too easy or boring and exerting a negative effect on their receiving peers. Therefore, the impact of transferred students on receiving students is theoretically ambiguous.

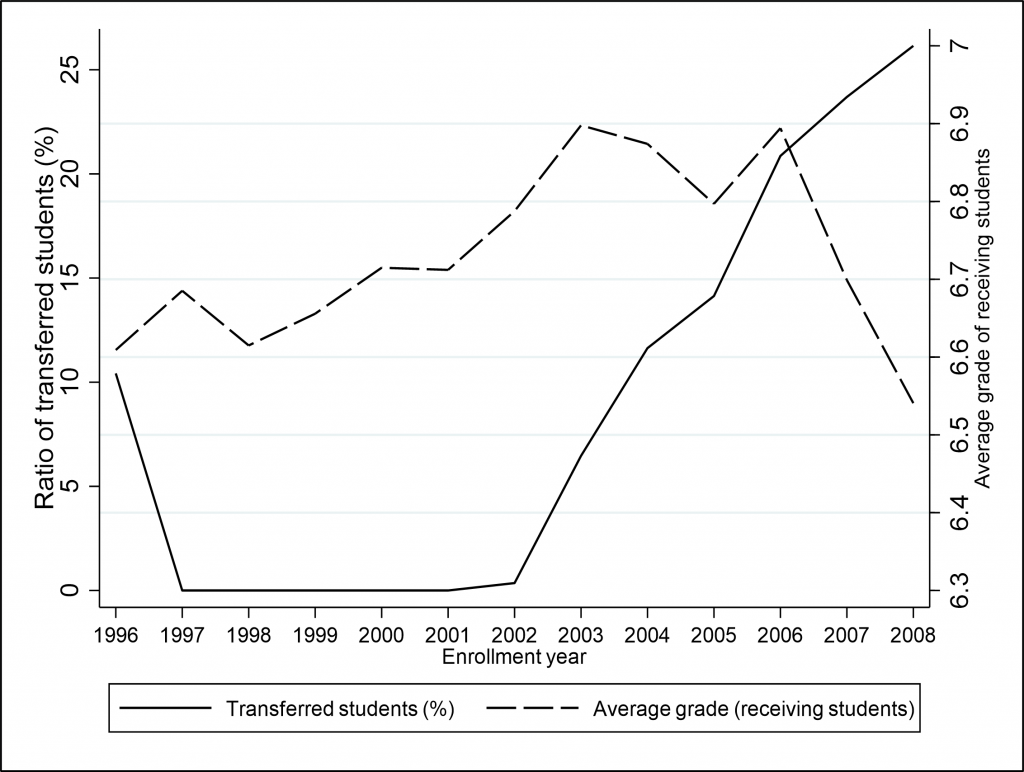

Figure 1 plots the average grade of receiving students (right-hand axis) and the percentage of transferred students by enrolment year (left-hand axis). While the average grade of students in receiving departments was increasing until 2003, since then it has followed a strong negative trend. At the same time, the percentage of transferred students was either zero or very small until 2003, then increased by a phenomenal amount to more than a quarter of the student population after just five years. The negative association between the share of transferred students and the average grade of students in receiving departments after 2003 provides an indication of a strong negative effect.

Figure 1: Percentage of transferred students and average grade of students in receiving departments

Note: The figure plots the average university grade of students in receiving departments (dotted line) and the ratio of transferred students, defined as the percentage of transferred students over the total number of students (continuous line).

Analysing the data, both at the aggregate (course) level and at the individual student level, we provide consistent evidence showing that transferred students exert a large negative effect on students in receiving departments. One standard deviation increase in transferred students leads to a 0.5 standard deviation decrease in grades and lowers the probability of passing a course by 0.1 standard deviations, on average.

This effect is larger as the percentage of transferred students increases and is stronger at the lowest quartile of the ability distribution and becomes less intense as we move to higher quartiles, leaving the top quartile intact. In other words, we find consistent evidence that it is the weakest students that are most affected. Finally, we highlight that in our setting the negative effect mainly operates through courses that are heavy on mathematics and statistics.

Overall, our research shows how a social policy that is meant to help financially constrained families and to alleviate inequalities has gone bad educationally, by lowering the academic achievements of receiving students. We very much hope that our research contributes to a more holistic cost-befit analysis of this policy that can examine its impact from the transferred students’ perspective, as well as look at the evidence from other departments and different academic fields.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying CEP Discussion Paper No. CEPDP1851

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Jordan Encarnacao on Unsplash