Research suggests that sport can have a positive effect in fostering social cohesion among those from different backgrounds. Yet to have this effect, it is necessary to overcome instances of discrimination that can prevent people from participating. Drawing on a field experiment in Norway, Robert Dur, Carlos Gomez-Gonzalez and Cornel Nesseler highlight the importance of using evidence-based policies to reduce discrimination in amateur football.

As football (or soccer) grows in popularity and reach, so does the need to understand its social impact. Amateur football has the potential to be a powerful social integration tool. Everyone understands its language and cultural barriers are low. Research shows how participating in a diverse football team can build social cohesion and improve perceptions and behaviours toward members of minority groups.

A key question is, however, whether it is actually easy to join an amateur football club, in particular for minority group members. Motivated by the large experimental evidence of ethnic and racial discrimination in labour markets, housing, education, and even dating, we have analysed discrimination in amateur football in a new study.

The project started in Switzerland. We contacted amateur football clubs via email, either using typical Swiss or foreign-sounding names, asking if it was possible to participate in a trial practice. Comparing the response rates between groups is a straightforward way to detect discrimination. The results revealed that people with a foreign-sounding name in Switzerland are approximately 10 percentage points less likely to receive a positive response to a request for a trial practice.

The results from this experiment attracted some attention, and the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Stiftung für Wissenschaftliche Forschung funded the scaling of the project in 22 European countries. Focusing on the most sizable foreign groups in each country, we found that individuals with foreign-sounding names are significantly less likely to receive a response. This result is consistent across all countries in the sample, although there are differences in magnitude. The lowest differences are below 4 percentage points in Ireland, France, and Portugal, whereas the highest are above 20 percentage points in Croatia, Hungary, and Austria.

The next logical research step was to test measures to reduce discrimination. Despite the clear societal relevance, causal evidence on how to reduce discrimination is rare. We collaborated with the Norwegian Football Federation (NFF) to design a policy that could reduce discrimination in amateur football. We designed a low-cost intervention in the form of an email message and tested its effectiveness in a field experiment.

The email pointed to the important role football can play in promoting inclusivity and reducing racism in society and called on the coaches to be open to all interested applicants. It also mentioned that studies had shown that discrimination in amateur football exists. The predicted and intended effect of the email was that coaches would be more likely to respond positively to requests to join a trial practice by people with a foreign-sounding name.

The NFF sent this email to coaches at a randomly selected half of all amateur clubs in Norway. We then waited for two weeks and contacted coaches at all amateur clubs with fictitious applicants asking to participate in a trial practice. Each club received only one email request, randomly signed by an individual with a foreign-sounding (Polish, Lithuanian, or Somalian) or Norwegian-sounding name. We categorised all the responses from the coaches and stopped collecting responses after six weeks.

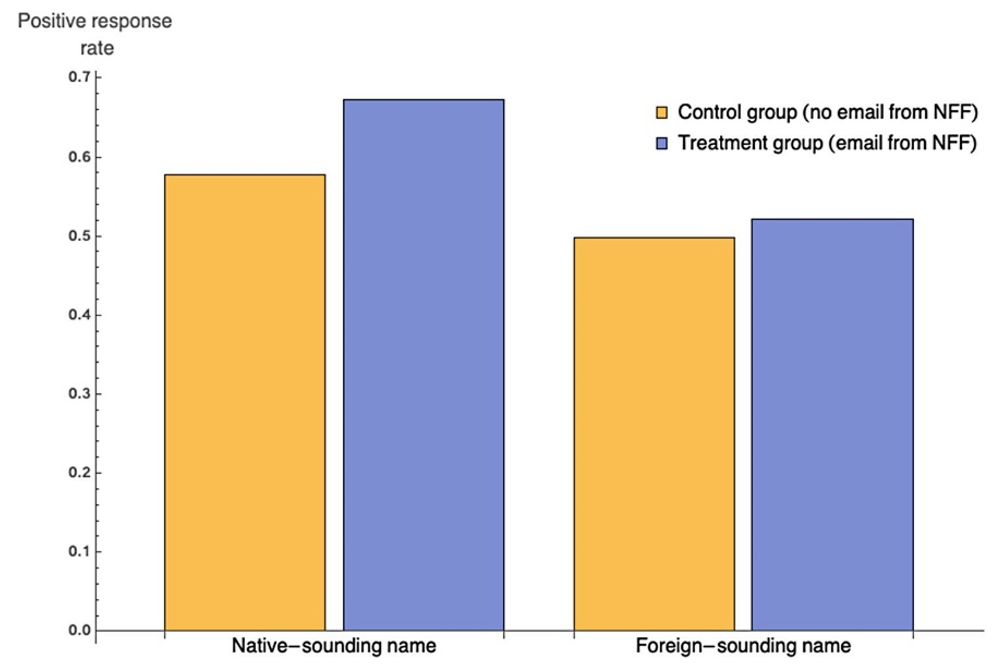

We obtained two main results. First, as in our earlier studies, we find substantial discrimination: people with a foreign-sounding name receive fewer responses. In this case, the difference in response rate is 8 percentage points. Second, the intervention from the NFF had an unexpected effect. Rather than shrinking the gap between people with native and foreign-sounding names, the email widened it, to more than 15 percentage points. Figure 1 shows this result below.

Figure 1: Share of positive responses to applications with native and foreign-sounding names for treatment and control group coaches

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies.

Strikingly, the increase in the gap is caused by coaches becoming much more open to requests from people with Norwegian-sounding names. A possible interpretation is that the email from the NFF encouraged coaches to expose more natives to intergroup contact by letting them join their team.

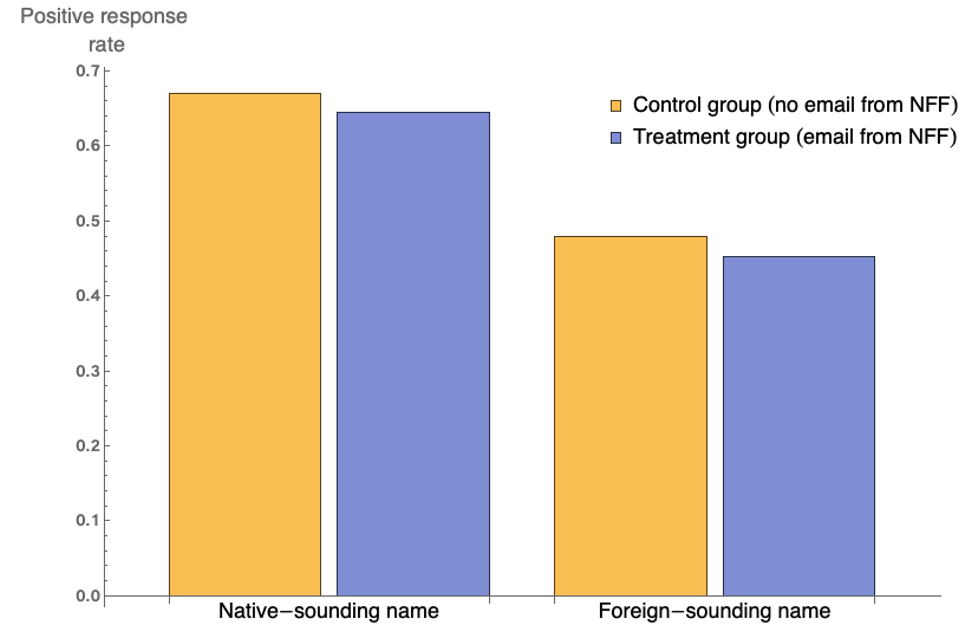

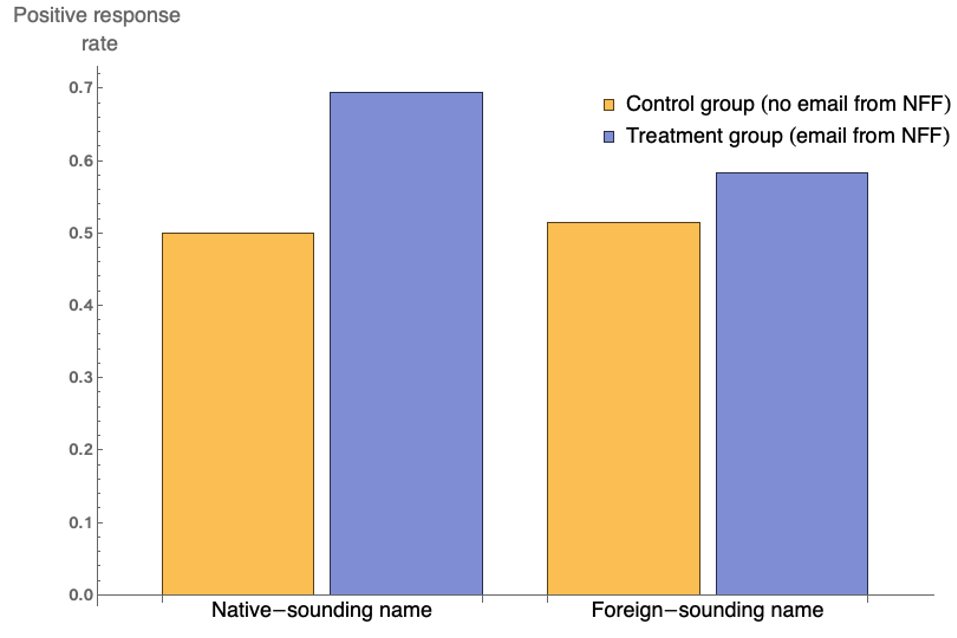

Further support for this interpretation follows from an analysis of how clubs in populous areas differ from clubs in less populous areas. Our data show that in less populous areas discrimination is much more severe and that the email from the NFF had no effect at all there. In contrast, in more populous areas, there is no discrimination by clubs that were not sent the email from NFF, whereas those that were sent the email from the NFF admit applicants with Norwegian-sounding names at a much higher rate. Figures 2 and 3 show these results.

Figure 2: Share of positive responses to applications with native and foreign-sounding names for treatment and control group coaches in regions with fewer than 100,000 citizens

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies.

Figure 3: Share of positive responses to applications with native and foreign-sounding names for treatment and control group coaches in regions with more than 100,000 citizens

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies.

Summarising, our field experiment shows that low-cost policies can have important effects on ethnic discrimination, but not always in the expected or intended way. Our results point to the importance of thoroughly testing interventions. Unfortunately, in practice, initiatives to reduce discrimination are rarely tested through large-scale field experiments. Much more research is needed in this area, and field experiments are well-suited to isolate the effect of anti-discrimination policies. We hope that academic researchers and governing bodies will more often join forces and pursue collaborations to fight discrimination using evidence-based policies.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Nathan Rogers on Unsplash