Most analyses of populism emphasise the divide that populist parties establish between ‘the people’ and a corrupt ‘other’. Drawing on a new study, José Javier Olivas Osuna argues that this construction of boundaries and borders between people is far less binary than is commonly recognised. His research suggests that populist parties frequently blur boundaries depending on the context, allowing them to create a ‘meta-us’ that acts as a common front against perceived threats.

Brexit, the Covid-19 pandemic, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – which has triggered the biggest refugee crisis in Europe since WWII – have brought borders back to the centre of policy debates. Borders are indissolubly linked to notions of sovereignty and citizenship. But borders are not static, they evolve, overlap and are part of domestic and international power struggles.

By making cultural, linguistic, or ethnic differences more explicit, populist leaders contribute to those individual boundaries turning into something closer to a political border. These bordering processes help categorise people and create new, or strengthen existing, distinct collective political identities.

Borders are an essential part of the logic of ‘cultural differentialism’ (or ‘differential nativism’) underpinning the ‘othering’ and exclusion of migrants, refugees and ethnocultural minorities. Individuals may selectively choose evidence that exacerbates inter-group differences to portray the out-group as inferior.

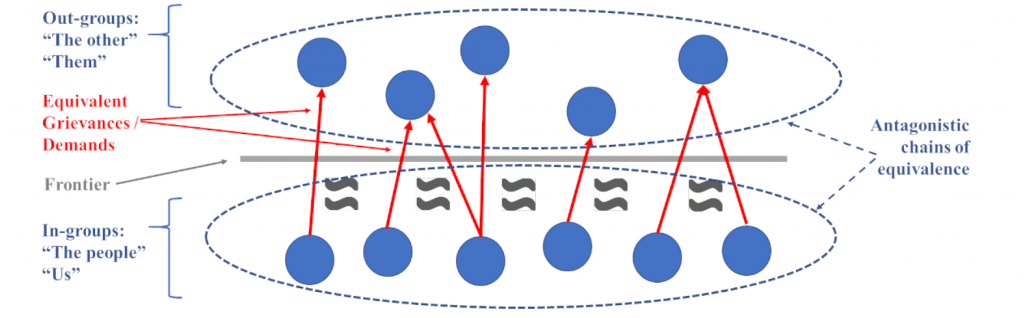

Figure 1: Equivalential chains in populism

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in the Journal of Borderland Studies.

Populist leaders often demonise the ‘underserving other’. The ‘elites’, ‘the caste’, ‘the colonisers’ and ‘the immigrants’ who do not really belong to the populists’ ideal ‘heartland’ and therefore should be removed from the demos. They argue that the ‘true’ or ‘authentic’ people must fight to achieve plenitude and ‘have their country back’. As Chantal Mouffe has argued ‘far from having disappeared, frontiers between us and them are constantly drawn, but nowadays they are drawn in moral categories’.

Populists compartmentalise society by creating or reinforcing internal frontiers and defining antagonistic ‘equivalential chains’ which bring together people with different, but comparable, fears, concerns, resentments, and grievances. Borders are an intrinsic component of the ‘populist logic of articulation’ and interpretative frames that shape how problems are identified and solved. In their attempt to re-enact their ideal heartland and recover a purportedly lost popular sovereignty, populist parties advocate (re)establishing political borders between states and reinforcing internal legal, economic, or cultural frontiers.

Borders and populism in radical right manifestos

Bordering policies highlighted by the borders literature are customarily justified via populist discursive elements, i.e., antagonism, morality, idealised construction of society, popular sovereignty and personalistic leadership. Populist tropes and rhetoric become common tools for those who seek to create new (or modify and strengthen existing) borders. In my research I explore the complex interaction between populism and borders through a content analysis of electoral manifestos of Vox, Rassemblement National (‘National Rally’, RN), the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and the Brexit Party.

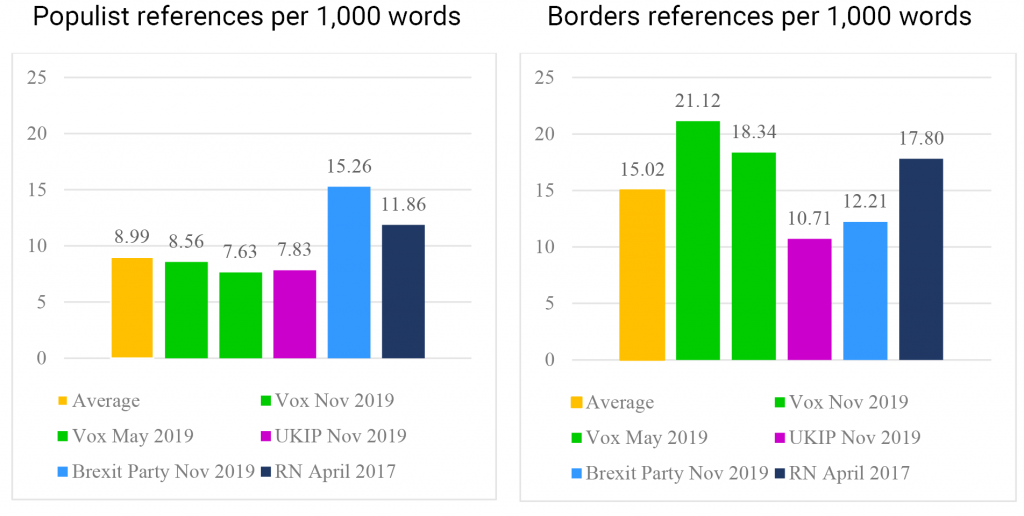

Figure 2: Density of populism and borders references coded per manifesto

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in the Journal of Borderland Studies.

As Figure 2 above shows, antagonism is the most salient populist attribute in the Brexit Party manifesto analysed. The populist idealisation of society is the most prominent attribute found in the RN and Vox documents, whereas morality references are the most frequent in the UKIP manifesto.

In the bordering discourse of the RN, references to exclusionary/discriminatory policies and to economic protectionism are very salient. The Brexit Party document emphasises the idea of protecting and recovering Britain’s sovereignty and the need to prioritise national interests over those of the EU.

Exclusionary policies and protection of British sovereignty are the most common references in the UKIP manifesto. Finally, whereas the Vox EU elections manifesto gives more salience to securitisation, protecting sovereignty and the critique of supranational institutions, the Vox Spanish elections manifesto emphasises identity and culture protection, as well as discriminatory policies.

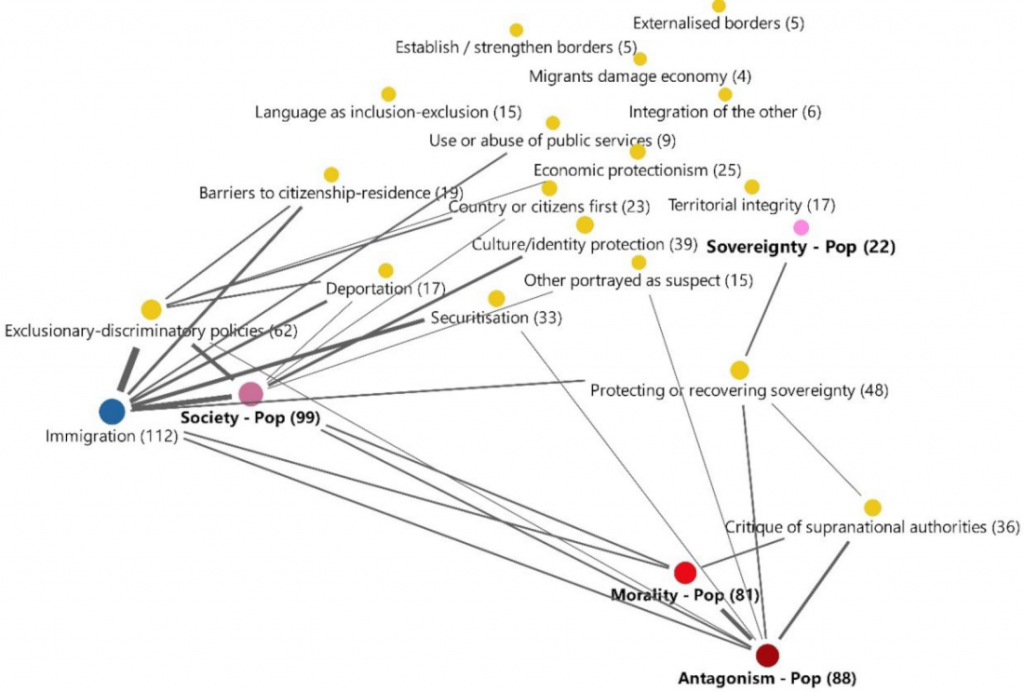

It is worth noting that borders and populism discursive references appear intertwined. This means that segments of text coded for different categories often overlap – for instance an antagonistic reference can be used with moral connotations and expressed to justify a deportation or the need for securitisation. A myriad of intersections between populist and borders were found, as shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Map of code intersections

Note: The total number of coded segments is shown in brackets. Lines capture intersections with a minimal frequency of five.

Nationality and religion are used to define the ideal society in these ‘othering’ discourses. For instance, Vox proposes the ‘deportation of illegal immigrants’ and of migrants who are lawfully in the territory but have committed serious crimes or repeated minor offences, while the RN requests barriers to the naturalisation of foreigners.

These parties articulate a model of society that is founded on traditional, usually Christian, values, which they claim are threatened by out-groups. This argument is often made with reference to Islam and Islamism, which these manifestos associate with radicalism, violence, and a lack of respect for certain democratic rights.

For instance, Vox proposes promoting ‘European values, uniquely embodied in Christian civilisation’, the ‘exclusion of Islamic education from public schools’ and following Hungary’s footsteps in creating a government agency for the protection of ‘endangered Christian minorities’. UKIP targets a repeal of the 2010 Equality Act which protects Black and Asian minorities. Moreover, UKIP declares that they ‘will promote a unifying British culture’ and Christian schools in the UK. Meanwhile, the RN declares that they will ‘defend the national identity, values and traditions of the French civilisation’.

These parties also antagonise supranational organisations, and in particular the EU. Vox refers to the ‘Europe that asphyxiates political freedom and cultural wealth of its member states’, while UKIP claims they will abolish ‘all of the EU-inspired legislation that binds us to EU legal institutions’. The Brexit Party promises ‘no further entanglement with the EU’s controlling political institutions’, and the RN proposes a referendum on EU membership ‘to regain our freedom and control over our destiny by restoring sovereignty to the French people’.

Morality is also used to justify exclusion and prejudices against ‘the other’. For example, UKIP warns against the ‘systematic and industrialised sexual abuse of under-age and vulnerable young girls by majority-Pakistani grooming and rape gangs’, and Vox insinuates that there are NGOs that collaborate with ‘illegal immigration mafias’. The RN claims defenders of globalisation are abolishing economic and physical borders to increase immigration and reduce cohesion among the French people, while the Brexit Party accuses the political establishment of conspiring ‘to frustrate democracy over Brexit’.

A populist international?

This exploratory analysis resonates with the findings of previous studies highlighting the similarities in othering discourses across populist radical right parties. The similarities found in the bordering policy proposals of these parties are relevant and could be framed within a wider process of discursive alignment between radical right populist parties in Europe.

Although Britain, France and Spain have historically been rivals and still maintain some ongoing border disputes – e.g. over Gibraltar, Calais, and fishery rights – their radical right parties do not give a high priority in their othering discourses to the citizens of each other. They construct supranational elites, Muslims and non-western European migrants and refugees as the main out-groups. These parties recognise each other and the people they represent as subject to an equivalent sort of exploitation and external threats.

Indeed, populist parties may adopt a flexible strategy and can emphasise or underplay state and supra-state borders creating a sort of hierarchical othering and a ‘meta-us’. The joint declaration signed by Le Pen (RN), Abascal (Vox), Orbán (Fidesz), Kaczyński (PiS), Salvini (Lega), Meloni (FdI), and other European right-wing leaders in July 2021, where they agreed to defend together ‘true European values‘ and their Judeo-Christian heritage, seems to confirm this growing notion of a ‘meta-us’ among radical right populist parties.

The Warsaw Summit, hosted by Mateusz Morawiecki (PiS) in December 2021 and the Madrid Summit, organised by Vox in January 2022, reunited many far-right leaders who pledged to defend Europe ‘against external and internal threats’, preserve states’ sovereignty and Christian values, and prevent ‘demographic suicide’. Despite their negative views on the EU’s institutions, these parties consider Europe as a civilisational space with physical and symbolic boundaries that encapsulate a distinct identity they embrace in addition to their national one.

Ambiguity about certain borders serves as a unifying discourse that establishes an additional ‘us’ that encompasses allied right-wing movements across state borders. Putin has employed a similar populist discursive strategy, portraying Ukraine as both an ‘antagonistic other’ and as part of the ‘self’. The selective blurring of borders and overstretched definition of the ‘Russian nation’ served him as justification for the intervention in Crimea and invasion of Ukraine.

In sum, populist leaders not only build or enhance borders but can also blur existing ones to strategically create new narratives of equivalence and layers of identity and otherness. The construction of a flexible ‘meta-us’ helps them normalise (re)bordering exclusionary policies and justify their radical policies.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in the Journal of Borderland Studies

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Vox España (CC0 1.0)

Hi. FWIW, I take a somewhat different view (neither for or against) of border “walls” in my book on democratic theory . (I mean, I’m against them personally, but I don’t think that’s particularly important.) It’s too long a story to go into here, but I guess it could be summarized by noting that I give a critique of the “stakes” view in favor of a more pragmatic geographic picture of jurisidiction divisions. Once one does that, everyone “inside” (for, say, a year) must have an equal say on public policy. If some focus on “othering,” others must be free to focus on “saming.” But if the majority doesn’t get its say on stuff like this, it’s not an authentic democracy. Admittedly, it’s a position that’s not particularly liberal, but if one thinks “natural rights” (except those that are required by any fair democracy) are fictions, one should exalt democracy. It’s true that where a majority of the populace is cruel, the polity is likely to be cruel, but democratic principles require equal treatment/protection, free speech, free association, etc., so the type of cruelty available in democracy is limited in some respects.

Anyhow, I’ve gone on too long. The book (which may now be pre-ordered in paperback) is here: https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781793624956/Democratic-Theory-Naturalized-The-Foundations-of-Distilled-Populism and a shorter (Teddy Rooseveltian) version, mostly just attacking the idea of a truly democratic “tyranny of the majority” can be read here: https://www.rjsp.politice.ro/why-radical-democracy-inconsistent-mob-rule

Sorry for the rant.