The war in Ukraine has cast a long shadow over European politics. Drawing on new research, Andre Krouwel, Alberto Lopez Ortega and Nicolò Cavallo examine the attitudes of voters in Italy toward Vladimir Putin and Russia during the campaign for the 2022 Italian general election.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February sent shockwaves across Europe. The subsequent war has had a major impact on European politics, with views on the conflict continuing to shape electoral dynamics within European states.

We have analysed the extent to which Italian voters supported Vladimir Putin’s military actions and geopolitical ambitions in the leadup to the Italian general election in September. Italy is an interesting case in relation to Russia as major right-wing parties have consistently and openly supported Putin, with half of the population voting for these parties in the 2022 election.

Both Giorgia Meloni, leader of Fratelli d’Italia, and Matteo Salvini of the Lega, have frequently expressed their sympathies for Moscow. Salvini even went as far as having pictures of him taken in Moscow’s Red Square wearing a Putin T-shirt, causing significant embarrassment among his party after the invasion. Surveys have found a majority of Italians oppose sending weapon shipments to Ukraine. At the same time, many Italians also valued the pro-EU and anti-Putin Draghi administration. This begs the question of which voters actually support Putin and how we can explain this support.

Putinism and the Italian right

Putin’s autocratic rule is associated with high levels of centralisation and the personalisation of power. Putin has avoided term-limits by switching between the roles of prime minister and president. He has also altered constitutional limits on power while preserving a façade of democratic practices. This may well resonate with those who embrace the uomo forte (strong man) ideal, which is deeply embedded in Italian political culture and public imagination.

Based on these considerations, we hypothesised that the highest support for Russia’s leader is most likely found among the most conservative strata of society, particularly among those who long for the return of an often ill-defined ‘golden’ past, those who hold traditional values and morals, and those who feel threatened by modern times and hold a pessimistic stance about the future. Thus, we expected a positive correlation between support for right-wing populist parties, such as the Lega and Fratelli d’Italia, and support for Putin.

We also expected to find a positive correlation between support for Putin and inclinations toward social conservatism, authoritarianism, and anti-EU attitudes. In contrast, we expected to find a negative correlation between support for Putin and trust in western institutions, such as NATO or the EU, as well as the United States as the ‘champion of the West’.

Finally, we expected to find that a predisposition toward political and social pessimism – the belief that the future of the country is far from bright – is associated with support for Putin. This derives from the assumption that those who long for a return to an idealised past tend to oppose recent changes in society, such as the more globalised economy with all its uncertainties and mass migration.

To test our hypotheses, we used unique data from a two-wave online panel study conducted in six EU member-states in the context of a Volkswagen Stiftung funded project entitled PRECEDE. Data was collected by Kieskompas (“Election Compass”), a Dutch political research institute. Emails for participants were collected through online Voting Advice Applications (VAAs) prior to the election.

Explaining support for Putin in Italy

Our analysis found a strong positive correlation between support for Putin and a higher likelihood of voting for the Lega or Fratelli d’Italia. In contrast, we found a negative correlation between support for Putin and a higher likelihood of voting for the centre-left Democratic Party. These results align with previous studies demonstrating a close connection between far-right movements and support for Putin. These ideological and affective links have also been found in surveys showing that populist voters trust Putin more than other voter groups.

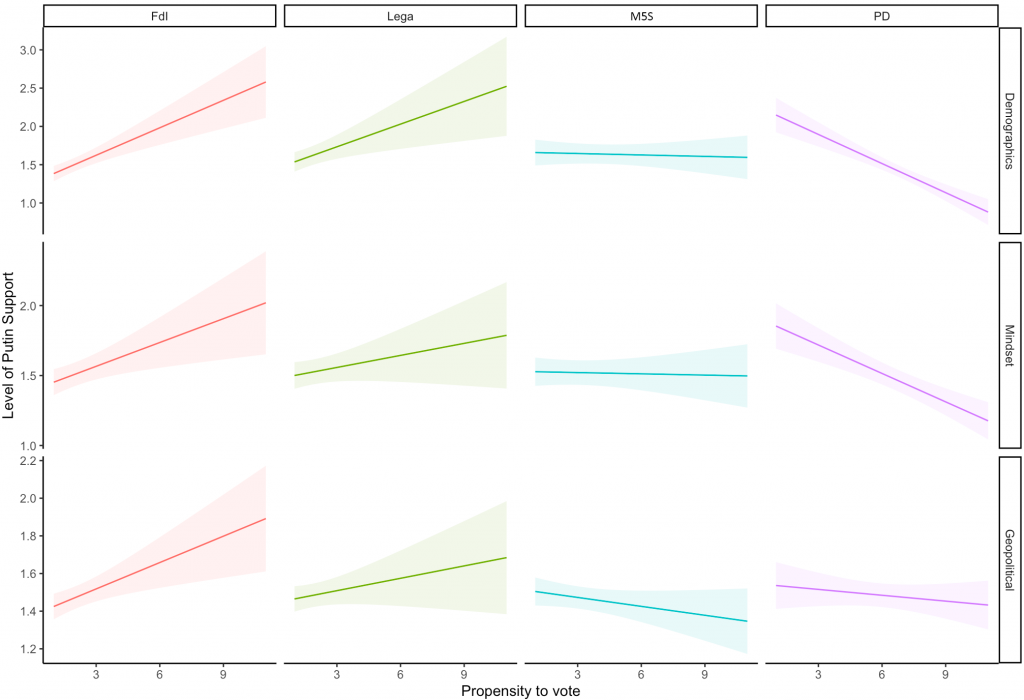

Figure: Relationship between support for Vladimir Putin and propensity to vote for Italian parties

Note: The parties shown in the figure are Fratelli d’Italia (FdI), Lega, the Five Star Movement (M5S) and the Democratic Party (PD).

The main results of our analysis are shown in the figure above. Although Meloni adopted a more critical stance toward Putin in the leadup to the 2022 Italian election, this does not appear to have alienated her voters, who we found were among the most pro-Putin of the Italian electorate. The picture is less clear cut for the Lega. Despite the party’s leader, Matteo Salvini, being more outwardly pro-Putin than Meloni, we found that Lega voters were less appreciative of Putin than would be expected.

An interesting finding from our analysis is that there is no relationship between support for Putin and likelihood of voting for the populist Five Star Movement. This is additional evidence that the Five Star Movement is a catch-all party in the sense that it mobilises discontented voters from across the political spectrum. The party adopts ambiguous positions on substantive issues such as citizenship, minority rights, and European integration, which has led some scholars to conclude that it constitutes a “populism without host ideologies”.

As expected, social conservatism, with its traditional outlook on society and politics, is positively associated with a favourable evaluation of Putin. However, having a pessimistic outlook for the future had a much weaker relationship with support for Putin. This is likely the effect of many other sources that could fuel pessimism, such as the deterioration of the natural environment, depletion of natural resources, democratic backsliding, and high levels of socio-economic equality to name a few. Although we did not find strong evidence for our second hypothesis, all the effects were in the expected direction.

Europe and support for Putin

Positive and negative evaluations of Putin seem to be closely associated with how Italians view the world around them. If we include respondents’ evaluation of European integration and their perception of the threat posed by Russia, then the explanatory value of our model substantially increases. This suggests that despite Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine, many Putin supporters do not perceive Russia to be a threat to their own security.

Many populist leaders, including Salvini, Marine Le Pen and Thierry Baudet, have argued that Putin is not a threat, but is instead merely correcting all that has ‘gone wrong’ in post-war Europe. This reflects opposition to the notion of an ‘ever closer supranational European Union’, which it is claimed poses a threat to European democracy.

For many, the fact that decision-making powers have been pooled at the EU level, while political legitimacy and accountability remain at the level of national parliaments, has resulted in a lack of transparency and an unresponsive model of politics dominated by technocratic bureaucracy. More extreme claims focus on alleged conspiracies to pursue the intentional destruction of nation states, cultural homogenisation and even ‘white genocide’ through the process of European integration.

Populists on the right like how Vladimir Putin is supposedly pushing back against this destruction of European culture and they are attracted to Putin’s – vague and unspecified – idea of a Europe that can be constructed through manifestations of a united national will. It is this mindset that explains why some voters can on the one hand reject the current political order while calling for a political project through which a unified European civilisation can be rescued from all its threats.

Note: The study on which this article is based is part of PRECEDE, a Volkswagen Stiftung funded project. The article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: kremlin.ru