Stigmatisation has long been recognised as one of the major obstacles to the success of populist radical right parties. But why are some individuals less susceptible to this stigma than others? Drawing on an original survey of members of the Sweden Democrats, Sofia Ammassari demonstrates the importance of personal networks to the willingness of party members to make their support public.

The September 2022 Swedish general election was a landmark event for the populist radical right Sweden Democrats. First, they became the second largest party in Sweden, and the largest member of the country’s right-wing bloc. Second, Swedish centre-right parties finally agreed to cooperate with the party in forming the government – a cooperation that had long been ruled out because of the Sweden Democrats’ extreme right past. For a populist radical right party with such a history, these outcomes were remarkable.

But how does the legitimation of a populist radical right party in the electoral arena, like that of the Sweden Democrats, translate at the societal level? Does populist radical right support become socially accepted, or does it remain stigmatised? In a recent study, I look at the stigma surrounding populist radical right support using an original survey of around 7,000 members of the Sweden Democrats, as well as interviews with 30 of them. In particular, I investigated which members were more likely to feel stigmatised, and why.

Stigmatisation and populist radical right support

Stigma has long been a distinctive feature of populist radical right parties, especially those with an extreme right past. Because of their anti-immigration agendas, these parties are seen as violating a strong social norm developed in western countries after WWII – that of not discriminating against ‘out-groups’ defined on the basis of their ethnicity, race, or religion. As such, populist radical right supporters can face severe social sanctions, including isolation from family and friends, and loss of employment.

Previous research has argued that members of populist radical right parties like the Sweden Democrats will largely be individuals who do not care about social sanctions. These people are said to be extremists, who do not mind defying social norms, and/or people with low socio-economic status, who have little to lose in terms of employment. However, this perspective overlooks how stigma is socially constructed. Put simply, whether you feel that being a populist radical right supporter carries stigma may also depend on the reaction of the people around you.

In my study, I therefore examined how feelings of stigmatisation among populist radical right party members are influenced by the political views prominent in their personal networks. These views can be gauged by looking at whether members have ever had any close contacts in the party, and at their educational level and employment sector – the latter two working as proxies for the political preferences of members’ acquaintances and colleagues.

Who feels stigmatised, and why?

In my survey, I measured whether respondents felt stigmatised by asking the extent to which they agreed with the statement: ‘It is not easy to publicly admit that I am a member of the Sweden Democrats’. As Figure 1 shows, about 58 per cent of respondents agreed that they were wary of revealing their membership in public. This suggests it is not true that people who join populist radical right parties like the Sweden Democrats are individuals that do not care about the stigma; on the contrary, membership is seen by most as a source of social discredit.

Moreover, since the survey was distributed at a moment (October-December 2021) when most Swedish centre-right parties had already expressed a greater openness to cooperating with the Sweden Democrats, we can see that political legitimation does not translate automatically into individual feelings of societal legitimation.

Figure 1: Stigmatisation among party members of the Sweden Democrats

Note: Respondents were asked to indicate their agreement with the following statement: ‘It is not easy to publicly admit that I am a member of the Sweden Democrats’.

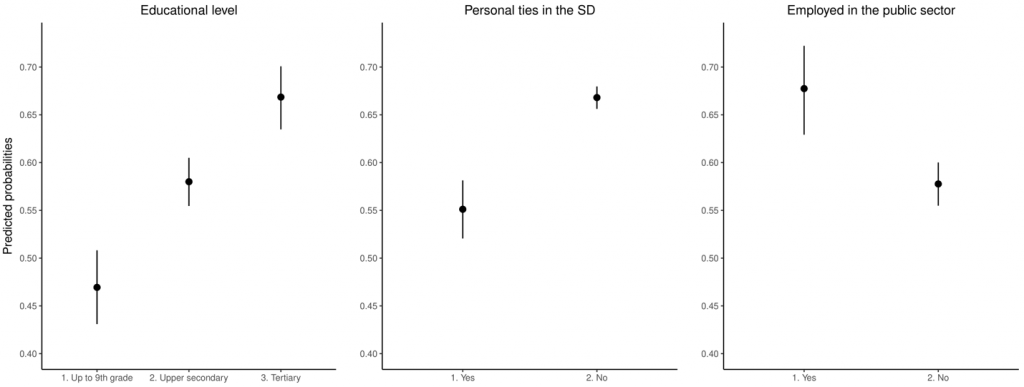

But who are those members that feel subject to the stigma surrounding the populist radical right? My results show that respondents’ educational levels, employment sector, and history of personal ties in the Sweden Democrats are all important factors.

First, as the left graph of Figure 2 shows, the higher the educational qualification achieved by members of the Sweden Democrats, the more likely they will be wary of revealing their membership. Second, the central graph in Figure 2 illustrates that those who have had relatives and/or friends in the party are less susceptible to stigma than those who have not. Being employed in the public sector also influences feelings of stigmatisation, with public employees considering their party membership more discrediting, as we can see from the right graph in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Predicted probabilities of feeling stigmatised among members of the Sweden Democrats

Note: The figure is based on 6,934 respondents and displays the predicted probabilities of feeling stigmatised with 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Notably, extremists and those with low socio-economic status did not feel significantly less stigmatised than moderates and members with a higher socio-economic status. This counters some of the prevailing wisdom and indicates that populist radical right stigma is best explained by social factors rather than ideological and socio-economic ones.

In addition to the large-scale survey, I also interviewed 30 members of the Sweden Democrats from the counties of Skåne and Stockholm. These interviews help to explain why some personal networks are less encouraging than others when it comes to revealing populist radical right party membership.

Populist radical right party members who work in the public sector or are enrolled in university find it hard to be open about their membership because they think their professional and social circles are filled with left-wing people. Accordingly, the social sanctions they would incur are quite high. For example, a college student told me: ‘The universities in Sweden are very, very radical leftie… After a while they learned I was a party member. When I walked around from courses to courses, well, they spat on the ground when they saw me’.

By contrast, having relatives and friends who are populist radical right party members reduces the stigma of joining and becoming active. For instance, it took one interviewee some time, and the reassurances of her partner, to actually show up at party meetings: ‘It became easier because my partner got more involved and got to know the right people. I was a bit nervous before, you know, what will the meetings be like – if there are a lot of racists and strange ideas among the people that are engaged’.

Consequences for the populist radical right party family

My findings indicate that the mere fact a populist radical right party is increasingly accepted in the electoral arena does not mean that stigma at the societal level will similarly fade away. This has important implications for the electoral and organisational growth of populist radical right parties.

It is not a coincidence that the Sweden Democrats still field fewer tertiary-educated and/or public sector candidates than other Swedish parties. It seems likely that people’s fear of making their membership public is partly what impedes populist radical right parties like the Sweden Democrats from putting forward their most educated and skilful members as candidates.

At the same time, when populist radical right party members have close contacts in the party, feelings of stigmatisation are attenuated. Members of the Sweden Democrats act as ‘ambassadors to the community’, mobilising new followers through their daily contacts.

Overall, therefore, not all populist radical right party members are oblivious of stigma, and those who are cannot be reduced to ‘extremists’ or ‘economic losers’. Rather, as my study demonstrates for the case of the Sweden Democrats, populist radical right stigma is largely affected by members’ personal networks.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in the European Journal of Political Research

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: News Øresund – Johan Wessman © News Øresund (CC BY 3.0)