Immigration has the potential to alleviate some of the pressure put on pension systems by Europe’s ageing population. But will this translate into increased public support for migrants? A new study by Tito Boeri, Matteo Gamalerio, Massimo Morelli and Margherita Negri shows that a better understanding of pay-as-you-go pension systems and population trends can lead to more positive attitudes toward migrants, but only among individuals who support non-populist parties.

Progress in medicine and reduced fertility rates are leading to unprecedented population ageing in most OECD countries and many emerging economies. For many of these countries, this will shortly translate into a significant increase in the old-age dependency ratios (the ratio between the number of individuals older than 65 and those between 20 to 64). For instance, the EU-27 average dependency ratio is estimated to double over the next 30 years, jumping from about 30% to almost 60% by 2050 (OECD).

These demographic trends are a potential concern for pay-as-you-go (PAYG) public pension systems. Under PAYG systems, contributions paid by current workers finance current retirement benefits. Hence, these systems can be sustained if the size of the retired population is not too large compared to the current working population. In some countries, however, the imbalance between contributors and receivers is expected to grow significantly. For example, the number of retired individuals for every 100 workers is expected to increase from 68.6 in 2018 to 105.7 by 2050 in Italy and from 51.7 to 88.6 in Spain (OECD).

Immigration and pay-as-you-go pension systems

Immigration can help alleviate the pressure on PAYG systems. Immigrants tend to be young (the median age within the population of migrants in Europe was 30.3 years in 2020 according to Eurostat) and have lower reservation wages than natives. As such, they are likely to join the working population of the hosting country. Estimates by the Italian National Institute for Social Security (INPS) indicate that the net social security contributions of migrants in Italy amounted to around 7 billion euros in 2017. In addition, INPS estimates that a full closure of borders in Italy would lead to a 38-billion-euro deficit in the social security system by 2040.

In Spain, the government has openly recognised that the pension system will not be sustainable without the contribution of foreign workers. Yet, anti-immigrant sentiments have been growing in many countries. In the Spring 2018 Global Attitudes Survey (Pew Research Centre), the median share of Europeans replying “Fewer” or “None” to the question “In your opinion, should we allow more immigrants to move to our country, fewer immigrants, or about the same as we do now?” was 51%. This share was 71% in Italy. Both in Italy and Spain, the share has increased since 2014.

An online experiment

In a recent study, we ask whether better knowledge of the functioning of PAYG pension systems and current demographic trends can make natives more willing to accept migrants. The main idea is that if individuals have limited knowledge of the challenges faced by PAYG systems, they might underestimate migrants’ positive contribution to the welfare of their country. Hence, correcting this lack of information may change attitudes toward immigration and lead to a higher willingness to accept migrants.

We tested these ideas through an online experiment in Italy and Spain in 2021. We treated a randomly selected set of participants with a video explaining how the payment of current pensions in PAYG pension systems depends on the contributions paid by current workers and how the ratio between the number of pensioners and the number of workers in their countries will grow substantially. We then looked at the effect of the treatment on i) respondents’ knowledge of the functioning of PAYG systems and demographic trends and ii) their attitudes towards immigrants.

The most important feature of our treatment, distinguishing our work from existing literature, is that we did not mention immigration in the video. This feature allowed us to test the indirect effect of providing useful information for evaluating immigrants’ contributions to the hosting country without explicitly stating such contributions. We believe this type of message has the advantage of being more immune to politics. Indeed, for a sensitive topic like immigration, it can be easy for anti-immigration parties to portray positive narratives about immigration as just one version of the facts and counteract them with alternative stories.

Furthermore, directly mentioning immigration might induce respondents to associate the treatment with leftist (or, more generally, pro-immigrant) parties, biasing the effectiveness of the treatment. The information we provide in our video is more “neutral” and less subject to this type of issue. Providing a treatment that does not mention the main topic of our analysis has the additional benefit of reducing the concerns of “experimenter demand effects” (i.e. respondents’ tendency to interpret the treatment as a cue for the experimenter’s objective and adapt their responses accordingly).

Key findings

Our results show that the treatment improves participants’ knowledge of pension systems and demographic trends. On average, treated respondents are 6 percentage points more likely to state that current pensions are financed by current contributions and 4.6 percentage points more likely to state that immigrants are net contributors to the welfare system. The treatment also increased respondents’ willingness to accept migrants (by around 2.6 percent) relative to the average response in the control group. However, at first sight, it did not seem to affect respondents’ opinions about the benefits of immigration on the pension system, the economy, and their country’s culture.

To better investigate these results, we studied whether the effect is heterogeneous among supporters of different political parties and split the sample into three groups. The first group comprises respondents voting for parties with clear anti-immigrant stances (Lega, Brothers of Italy, Vox) or with ambiguous and populist positions towards immigration (Five Star Movement). The second group consists of the voters of all other parties who do not support anti-immigrant stances. Finally, the third group comprises undecided voters, who did not indicate any favourite party in their answers to our questions.

Figure 1 shows that our video increases the knowledge of pension systems and demographic trends for participants in all three groups, with a stronger effect on supporters of anti-immigrant and populist parties and undecided voters.

Figure 1: Effect of video on knowledge of pension systems and demographic trends

Note: Effect of treatment on the probability that participant correctly answers “True” to both of the following questions: “Current pensions are financed by contributions paid by current workers. In your opinion, is this statement true or false?” and “By 2050, the number of pensioners in Italy/Spain could increase more than the number of workers. In your opinion, is this statement true or false?” For more information, see the authors’ accompanying CEP Discussion Paper.

Note: Effect of treatment on the probability that participant correctly answers “True” to both of the following questions: “Current pensions are financed by contributions paid by current workers. In your opinion, is this statement true or false?” and “By 2050, the number of pensioners in Italy/Spain could increase more than the number of workers. In your opinion, is this statement true or false?” For more information, see the authors’ accompanying CEP Discussion Paper.

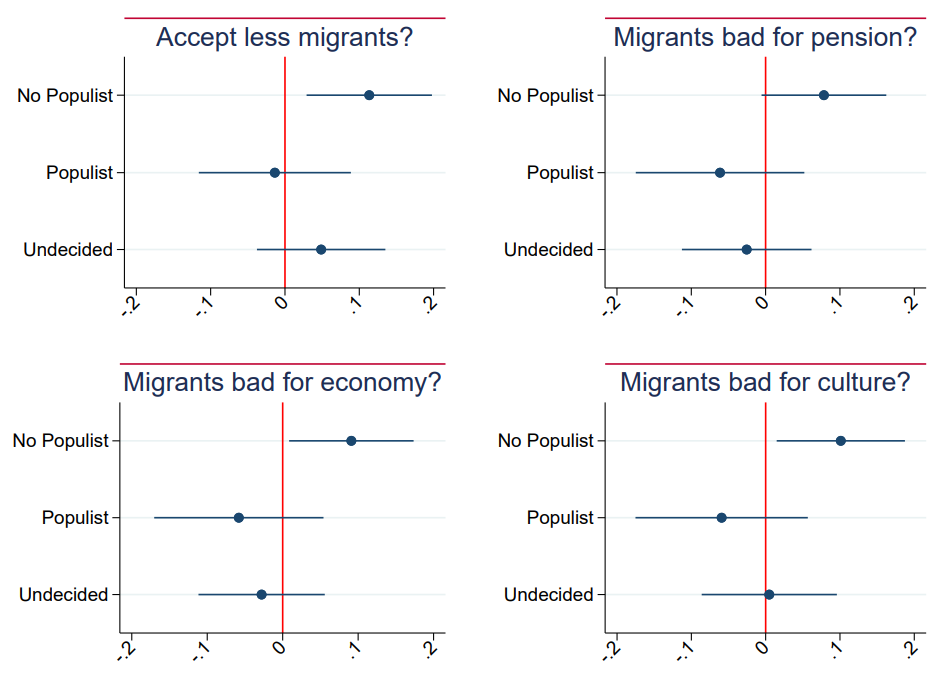

However, as Figure 2 shows, the treatment improves opinions about migrants and willingness to accept them only for individuals not supporting anti-immigrant and populist parties.

Figure 2: Effect of video on attitudes toward migrants

Note: Effect of treatment on respondents’ level of agreement with the following statements: “the country should accept fewer migrants”; “migrants are bad for the pension system/the economy/culture”, by party supported by the respondents. Answers range from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). For more information, see the authors’ accompanying CEP Discussion Paper.

Note: Effect of treatment on respondents’ level of agreement with the following statements: “the country should accept fewer migrants”; “migrants are bad for the pension system/the economy/culture”, by party supported by the respondents. Answers range from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). For more information, see the authors’ accompanying CEP Discussion Paper.

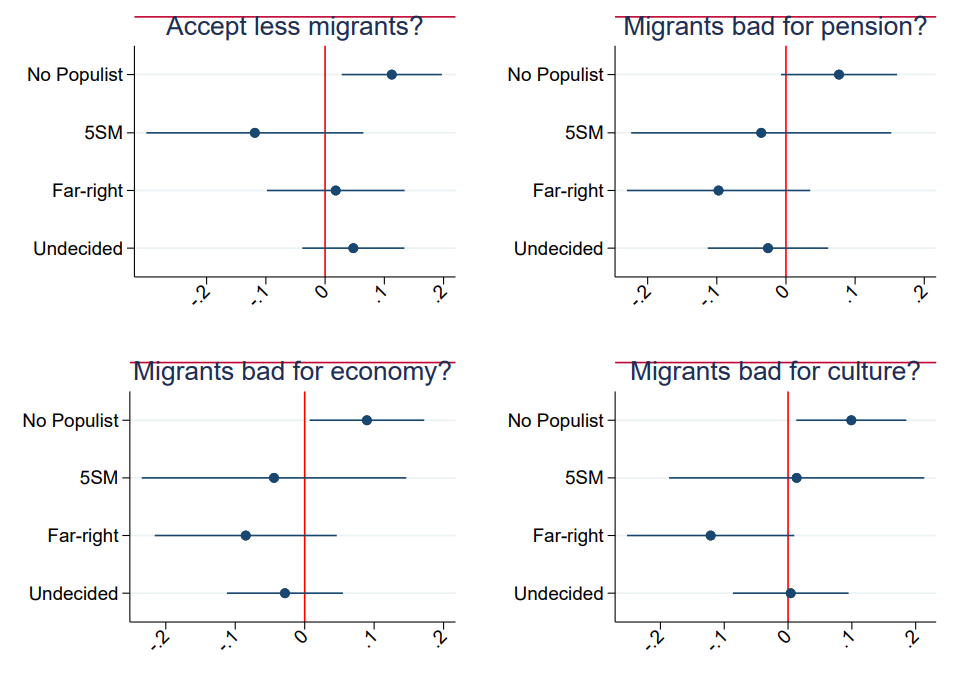

Three different channels can explain these results. The first is ideology. To investigate this possibility, we exploit the difference between far-right parties like Lega, the Brothers of Italy, and Vox, and the Five Star Movement, a catch-all populist party that is harder to place on the left-right axis. As shown in Figure 3, the ideological position of the Five Star Movement’s supporters is closer to that of non-populist voters.

Figure 3: Ideology of respondents based on political party support

Figure 4: Effect of video on attitudes toward migrants with Five Star Movement supporters separated from supporters of far-right parties

Note: Effect of treatment on respondents’ level of agreement with the following statements: “the country should accept fewer migrants”; “migrants are bad for the pension system/the economy/culture”, by party support with the Five Star Movement’s (5SM) supporters separated from supporters of other (far-right) populist parties. Answers range from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). For more information, see the authors’ accompanying CEP Discussion Paper.

Note: Effect of treatment on respondents’ level of agreement with the following statements: “the country should accept fewer migrants”; “migrants are bad for the pension system/the economy/culture”, by party support with the Five Star Movement’s (5SM) supporters separated from supporters of other (far-right) populist parties. Answers range from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree). For more information, see the authors’ accompanying CEP Discussion Paper.

A second possible explanation is that lower cognitive skills characterise supporters of populist parties. However, if this was true, we would likely not find such an effect from the treatment on these respondents’ knowledge of the pension system and demographic trends, as shown in Figure 1.

Although we cannot fully exclude the impact of ideology and cognitive skills, our preferred explanation for the ineffectiveness of our treatment on the opinion of populist voters relates to (a lack of) trust. Recent studies have shown how the sequence of crises of the last two decades has significantly reduced trust in institutions. The strategic response of populist parties who entered political competition has been to offer simple policy commitments to capture disillusioned voters with the lowest levels of trust in representative democracy. Hence, the populist voters in our representative group are likely to show low trust and a high focus on existing commitments.

The same argument is likely to apply to undecided voters, who are probably the most disillusioned with mainstream institutions and parties. Indeed, an analysis of responses to the European Social Survey provides descriptive evidence that populist and undecided voters have lower levels of trust in their country’s parliament, politicians, political parties, and the European Parliament than non-populist voters.

Therefore, for these voters, any message aimed at increasing the knowledge of a “potential” benefit from immigration goes astray because (1) the potential benefit may not arrive to them given their distrust in elites and policies proposed by mainstream parties, and (2) they subscribe politically to the parties that make unconditional commitments to anti-immigration policies, irrespective of any information they may receive.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying CEP Discussion Paper, Pay-as-they-get-in: Attitudes towards migrants and pension systems

The article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Jem Sahagun on Unsplash.