In contrast to Italy in 2022, Spain did not experience a clear shift to the right in its general election on 23 July. Davide Vampa provides evidence of the diverging trajectories followed by these two southern European countries.

“The hour of the patriots has come”, thundered Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni in a speech in support of the far-right Vox party a few days before the Spanish general election. The hope of the leader of Brothers of Italy, fuelled by favourable pre-election polls, was to see a clear turn to the right in Spain, thus confirming a general trend in Europe. Cultivating the idea of an oxymoronic international alliance of nationalists, Meloni envisioned a scenario where Spain would be allied with Italy, Poland, Finland and other EU member states led by conservative and radical-right parties.

The hopes of Meloni and other more radical sectors of the European right, however, were dashed on 23 July. The wave that started with the triumph of the Italian radical-right almost a year ago seems to have subsided. As I have previously suggested, the political-electoral convergence between the two main southern European countries has not materialised. The results of the Spanish election provide plenty of evidence for this.

Democratic resilience

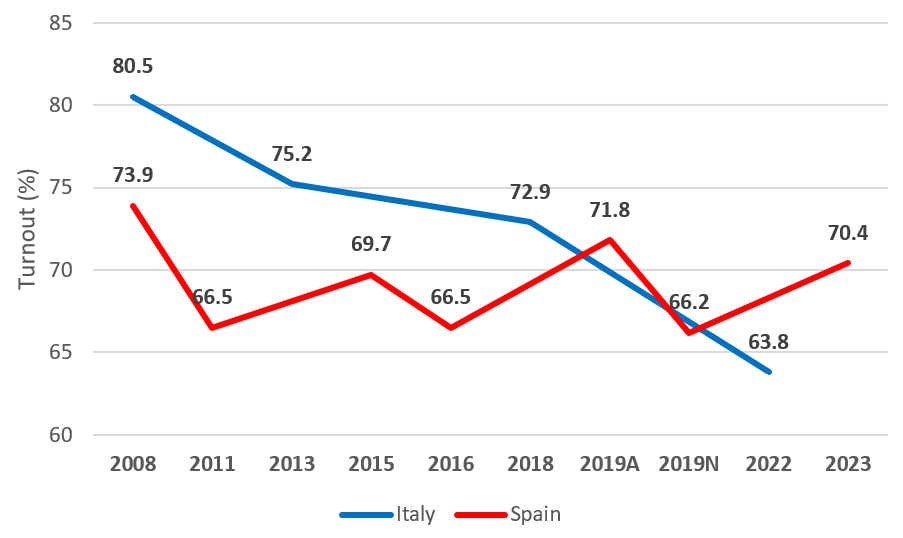

First, if we consider participation as an important aspect of the democratic fabric of the two countries, the two recent elections give us a picture of divergence. In Italy, the 2022 general election was marked by the lowest electoral turnout since the birth of the Italian republic after the Second World War. As shown in Figure 1, in 15 years, electoral participation in general elections has plummeted from over 80%, one of the highest in Europe, to just over 60%, one of the lowest. Meloni’s victory took place in a context of general demobilisation and growing apathy among citizens.

Figure 1: Electoral turnout in Italy and Spain since 2008 (general elections)

Sources: Italian Interior Ministry (Ministero dell’Interno) and Spanish Interior Ministry (Ministerio del Interior)

On the other hand, in Spain, despite the political and socio-economic challenges of recent years, levels of democratic participation do not seem to have eroded as significantly as they have in Italy. In 2008, at the start of the financial crisis, Spain had lower voter turnout than Italy, but it has not experienced the same prolonged decline in the years since. Moreover, in contrast to the 2022 Italian election, the 2023 Spanish election witnessed a substantial increase in participation, even though it was held during the hot summer period. This surge in participation could also be attributed to a more open and competitive electoral climate in Spain.

Recovery of the mainstream

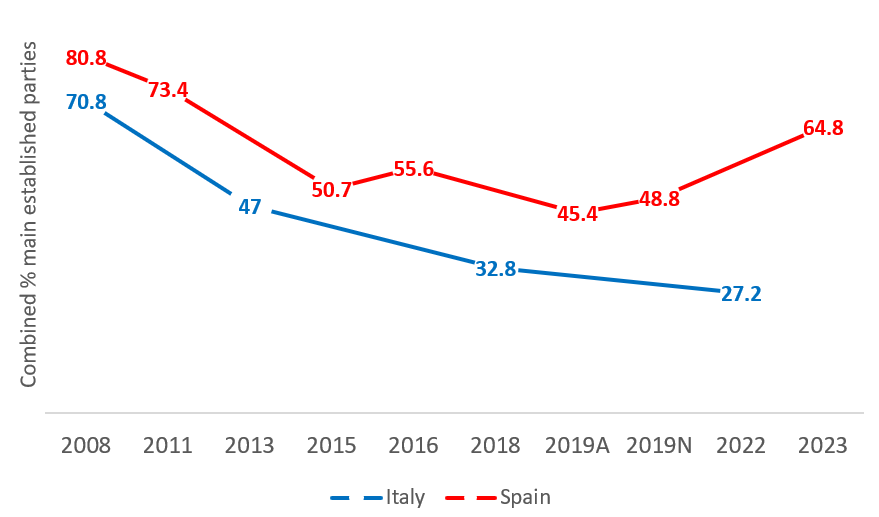

Another notable difference between the two countries, also anticipated in my previous blog piece, is the continued strength of the established parties that usually constitute the so-called “mainstream”. In Italy, even if we include the party of the late Silvio Berlusconi in this category (a problematic choice in itself), we can see how the political area occupied by what was considered mainstream in the 1990s and 2000s has shrunk dramatically, from over 70% in 2008 to less than 30% in the last elections of 2022 (Figure 2). Indeed, much of the electoral competition in Italy seems to take place within the populist camp rather than between populists and more traditional parties.

Figure 2: Combined share of the vote won by the two main “established” parties in Italian and Spanish general elections since 2008

Sources: Author’s own calculation based on data from Italian Interior Ministry (Ministero dell’Interno) and Spanish Interior Ministry (Ministerio del Interior)

In Spain, on the other hand, the 2023 election marks an important return of competition between the two major parties. Both the incumbent Socialist Party (PSOE) and the opposition conservative People’s Party (PP) gained votes at the expense of more radical competitors and various regionalist and pro-independence parties. In short, even if they have not returned to pre-crisis levels, the PSOE and PP have demonstrated much higher levels of electoral resilience than similar parties in Italy and even in other European democracies.

Volatility and fragmentation

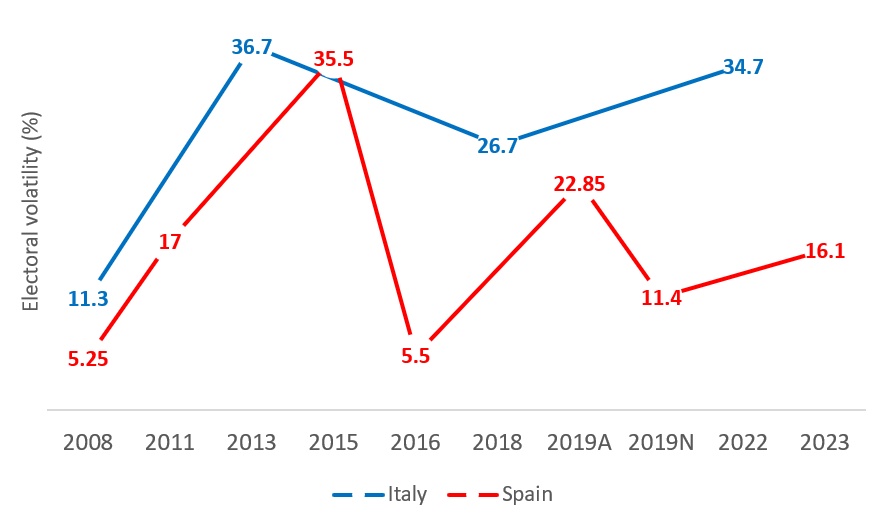

Both Italy and Spain have been characterised by high political instability over the last 15 years. This is evident from the significant level of electoral volatility observed in both countries during the post-financial crisis period. Additionally, both the 2022 Italian election and 2023 Spanish election took place earlier than expected. Yet only Italy continued to display some of the highest levels of volatility in Europe. In Spain, on the other hand, the dramatic electoral recovery of the PP at the expense of Vox and Ciudadanos has led to only a moderate increase in volatility which remains at much lower levels (less than half) than in Italy (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Electoral volatility in Italian and Spanish general elections since 2008

Sources: Emanuele (2015) and for 2023 Spanish election, author’s own calculation based on data from Spanish Interior Ministry (Ministerio del Interior)

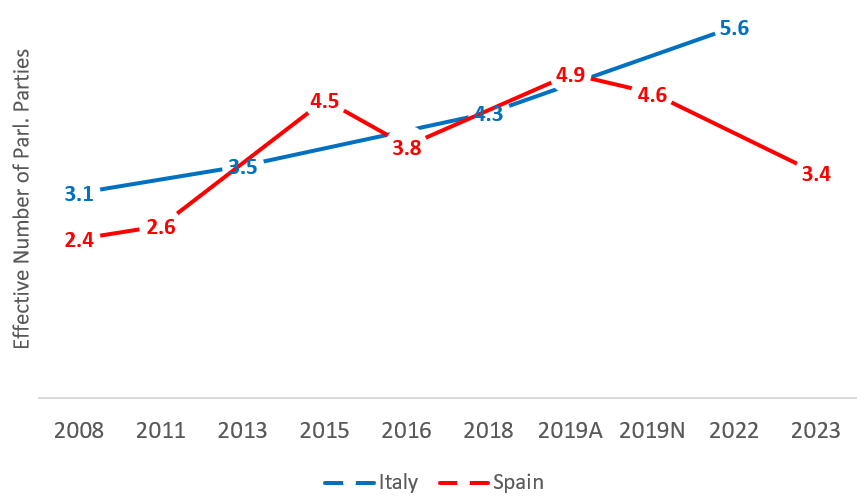

The 2022 election also seems to have further increased the fragmentation of the Italian party system in both its electoral and parliamentary arenas, as shown in Figures 4 and 5. While the right side of the political spectrum managed to form a relatively united front, the main opposing parties split into three much weaker groupings, which were in turn internally divided.

In contrast, in Spain, after years of growing fractures in the political space, the 2023 election saw a return to more “simplified” politics. Yet this does not mark a full restoration of the two-party system of the 1990s and early 2000s. Instead, a rather balanced bipolar system has clearly emerged, dominated by two main parties – the centre-left PSOE and the centre-right PP – each flanked by a radical left (Sumar) and radical right (Vox) competitor/partner, respectively.

Figure 4: Party system fragmentation (electoral arena) in Italy and Spain since 2008

Sources: Casal Bértoa (2023) and for 2023 Spanish election, author’s own calculation based on data from Spanish Interior Ministry (Ministerio del Interior)

Figure 5: Party system fragmentation (parliamentary arena) in Italy and Spain since 2008

Sources: Casal Bértoa (2023) and for 2023 Spanish election, author’s own calculation based on data from Spanish Interior Ministry (Ministerio del Interior)

Thus, the Spanish party system shows some relative stabilisation when compared to the ongoing changes in the Italian political landscape. Yet post-election developments in Spain may leave the country in a much more uncertain position than Italy, which, surprisingly, experienced a swift process of government formation in 2022. This was partly due to a voting system that rewarded large pre-election coalitions (while punishing a divided opposition) and allowed Giorgia Meloni to secure an overwhelming parliamentary majority, promptly elevating her to the position of head of the government.

In contrast, the situation in Spain is less straightforward. The balance between the left-wing and right-wing camps makes it challenging to predict who will succeed in forming the executive. The incumbent Prime Minister, Socialist Pedro Sánchez, managed to maintain his parliamentary base almost intact, and though lacking a majority, he could potentially rely on external support or abstentions from regionalist or sub-state nationalist parties.

On the other hand, the road seems more difficult for PP challenger Alberto Núñez Feijóo. Despite winning the largest number of seats, the PP does not have an absolute majority, even in alliance with Vox, and it appears unlikely that regionalist and sub-state nationalist parties would be willing to prop up a right-wing coalition that includes sectors openly hostile to regional autonomy.

While the Spanish political system has emerged from the July 2023 election in a relatively healthy and stabilised state, important questions remain about who will lead Spain in the coming months and years. A prolonged period of uncertainty could undermine the progress made in recent years and plunge the country back into a period of crisis and instability.

For more information, see the author’s recent book, Brothers of Italy: A New Populist Wave in an Unstable Party System (Palgrave Macmillan, 2023)

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Aitor Serra Martin/Shutterstock.com

There was never a widely anticipated rise in the far right vote, except in the mind of foreign media and commentators. It was always rather a matter of how much it would go down.

Indeed, this is also what I argued in a previous blog post: Spain was unlikely to follow Italy and clearly move to the right, and the election has confirmed this.