Spain’s incumbent Prime Minister, Pedro Sánchez, will require the support of Catalan independence parties if he is to form a new government. Rubén Díez García argues that the current situation underlines the influence Spain’s democratic transition continues to have on its politics.

To fully understand the current sociopolitical context in Spain, it is important to appreciate the democratisation process that began over half a century ago with the country’s transition to democracy. To do so, we must wield alternative concepts to those commonly used by analysts, politicians and the media.

Traditional categories, such as left and right, or conservative and progressive, are widely and frequently used, especially in times of political contention, since they help interpret key developments such as election results. However, they lack the necessary strength to account for the severe political crisis present in Spanish democracy, which has its origins in the black holes of the transition process.

Among the unintended effects of this process, I highlight two. On the one hand, the persistence of ETA terrorism until the 2010s and conflicts of a regional, nationalist and separatist nature between the central state and Spain’s Autonomous Communities have emerged from an unfinished territorial model. This model lacks normative and democratic values to guide the actions of political elites: a culture of federalism based on shared responsibility towards the political community and the belief in equality among Spaniards.

On the other hand, we have seen the significant presence of political parties in public life that, to varying degrees, have been tempted to colonise institutions, using them for partisan and clientelist interests across the regions, especially in Catalonia and the Basque Country, to promote national construction projects. These are just two examples among many of how Spain’s democratic transition continues to shape its politics.

Constitutional competition

The 2023 Spanish general election revealed the definitive configuration of two blocs led by the People’s Party (PP) and the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE). However, these blocs are not defined so much by an ideological axis, but by a constitutional one, reflecting a constitutionalist bloc comprised mainly of the PP and Vox, and a de facto confederal or plurinational bloc incorporating the PSOE and Sumar.

This dependence materialises in the subservience of both main parties to nationalist and/or separatist organisations and populist forces, either on the left or the right of the political spectrum. They have both succumbed to a populist temptation in recent years to either mobilise their social bases or control the levers of the state and maintain their positions, not just as political authorities, but as power wielders. Among the most serious instances are illiberal practices and the partisan handling of institutions. We have also seen discursive populism embodied in slogans or phrases during electoral campaigns.

In the constitutionalist bloc, the PP has been in a clear position of subservience to the political agenda and discourse of Vox in recent years. This relationship is the real Achilles’ heel for the party, as it divides and/or turns away their potential social base of voters and mobilises the vote of the opposition, which partially helps to explain their recent electoral results falling below expectations.

Meanwhile, in the national context, the rise of Vox represents the most radical and essentialist drift of constitutionalism in response to separatism and the Catalan process. On a global or international scale, it represents a cultural backlash against identity politics stemming from alternative and social justice movements.

In the confederal bloc, the PSOE has aligned itself with Sumar and formerly with Podemos, who both aim to embody the agenda of alternative social movements in the institutional arena. Their leaders are activists or former activists, representatives of civil society, academics and intellectuals. Their existence can only be understood because of the developments within the mobilisation of the 15-M movement in 2011 and the different actors that took the lead in that broad framework of collective action and subsequent institutional formalisation.

The third pole of the confederal bloc is comprised of regionalists, nationalists and independence supporters. The empathy that the leaders of Sumar and Podemos feel towards these actors is best understood as a reflection of their emotional connection with the idea of the common (the commune), municipalism and the experience of social and political movements for social justice, along with the Latin American populist mystique and its plurinational agenda.

Indeed, Sumar seems to have taken the initiative to negotiate with the Catalan party Junts and its leader, Carles Puigdemont, the former President of Catalonia who has been a fugitive from justice since 2017. Everything points to Junts potentially holding the key to incumbent Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez being able to form a new government.

The 2023 election

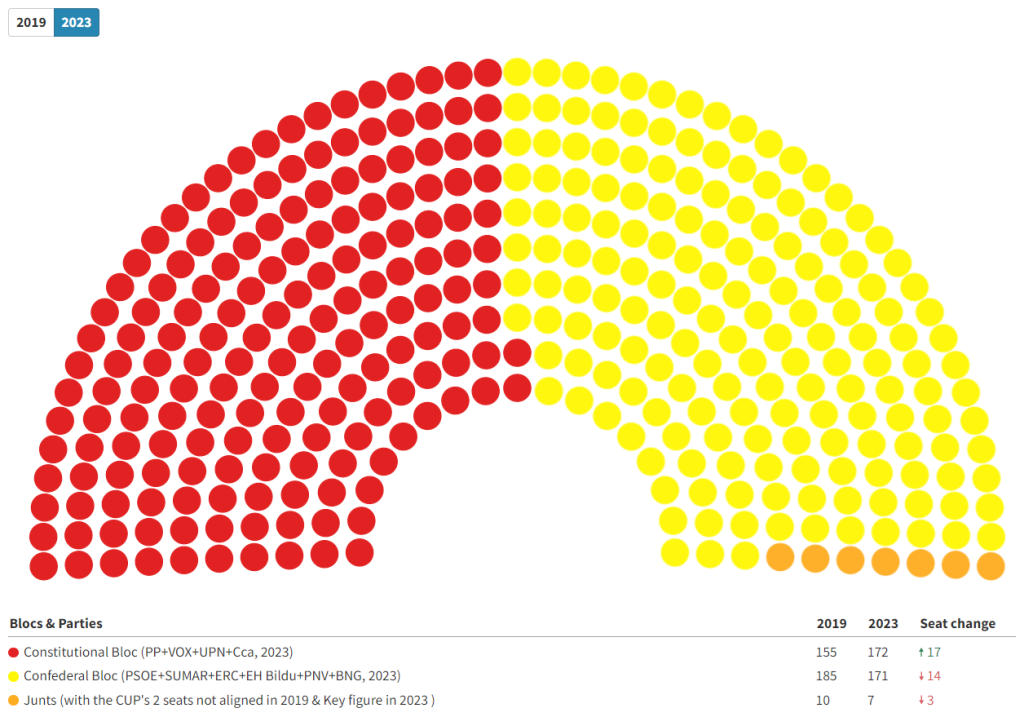

The Spanish political landscape underwent substantial change between 2019 and the 2023 election. The constitutional bloc gained traction and increased its seats from 155 to 172, further solidifying its position in the political landscape following the positive results it obtained in regional elections earlier in the year.

The confederal bloc saw its presence reduced in parliament, winning 171 seats compared to the 185 gained in 2019. Nevertheless, this bloc remains the best placed to form a government. It could achieve this by adding the seven seats of Junts, which did not align with the government following the 2019 election but now holds a key position.

Figure: Distribution of seats in the Spanish Parliament following the 2023 general election

Source: Created by the author using Flourish. The full visualisation is available here.

The present situation is far from new for Spanish politics. Nationalist parties on both sides of the political spectrum have previously made deals with the PSOE and PP when they needed it. Until recently, ETA had made demands of the government at gunpoint, with the support of political allies in the Basque Country. In Catalonia, the separatist movement has led a direct national-populist challenge to the Spanish state.

These elements have in turn prompted a response within Spanish society, seen in the civic rebellion that emerged in the mid-1990s against ETA, the resistance of Catalan civic and constitutionalist associations to linguistic immersion and the separatist process, and the defence of the rights of Basque and Catalan citizens who identify as Spanish. These struggles gave rise to the now-defunct Union, Progress and Democracy (UPyD) party and the ill-fated Ciudadanos, both examples of constitutionalist parties.

The question that faces Spain now is whether a confederal coalition government led by Pedro Sánchez and the PSOE is the least worst option. This government would likely be unstable and would further polarise Spanish society, given it would rest on a platform of movements like Sumar alongside nationalist and separatist forces. The demands of these actors would weigh heavily on the government’s actions.

While some observers regarded the 2023 election result as a triumph over the PP and a rejection of the politics of Vox, the reality appears more complex. Given the gaps that remain in Spain’s democratic transition, a confederal alliance that incorporates separatist, nationalist and populist organisations – including some leaders convicted of sedition – might simply risk deepening the country’s political crisis.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Alex Segre/Shutterstock.com