The sharp increase in inflation across Europe over the last two years has led to calls from some actors for a policy of wage restraint to prevent a vicious circle of price rises. Yet as Martin Höpner, Anke Hassel and Donato Di Carlo write, the fact that “wage restraint” can be understood in multiple different ways has created confusion about the link between wages and prices.

At the end of June, we participated in an interesting panel at the Council for European Studies conference in Reykjavik, Iceland. The panel dealt with wage policies in the current inflationary scenario which emerged with the price increases since mid-2021. The panellists analysed wage developments in several Scandinavian and southern European countries. We presented a paper on Germany. No matter which country was considered, the punchline of the papers always seemed to be the same – that their country, according to the authors, was a clear case of wage restraint.

This is strange. The European Central Bank (ECB), for example, notes a significant and gradually increasing wage pressure for the period under consideration. The same can be said of other international organisations. How do such different diagnoses come about and against which benchmarks are they measured? And can an entire continent, which can be described as a semi-closed economy (at least in comparison to its member states), engage in wage restraint? Restraint vis-à-vis whom, actually?

The problem is not that some base their diagnoses on better data than others. Rather, the protagonists of the debate have different meanings of wage restraint in mind and, accordingly, find it hard to agree. In the following, we distinguish between three concepts of wage restraint. The first two relate to wage restraint as falling real wages and wage restraint as a downward deviation from the so-called Golden Rule of wage-setting. The third concept, relational wage restraint, gets too little attention in the debate in our view. However, it is crucial for economic developments in a common currency area.

Wage restraint as falling real wages

When nominal wages rise less than price increases, the result is a loss of real wages (purchasing power) and an accompanying loss of consumption. This is what many experts have in mind when they use the term “wage moderation”. Nominal wage increases and inflation can be compared well ex post – no methodological problem arises. However, it is less clear whether this can be used to infer any behaviour on the part of actors in charge of wage policy, since the annual inflation rate is partly unknown at the time of negotiating wage settlements.

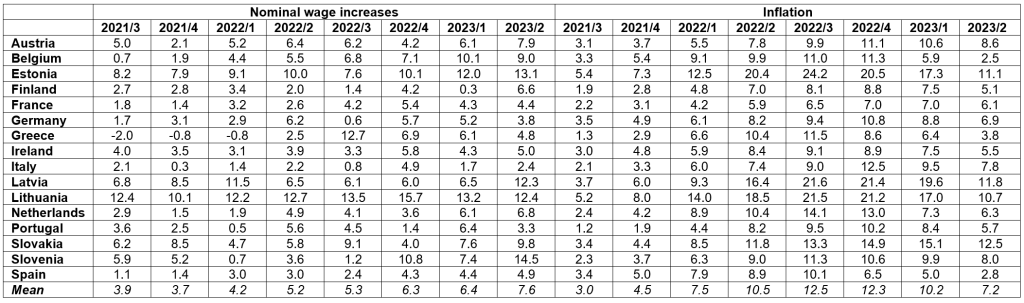

Between the summers of 2021 and 2022, all relevant actors were surprised by the speed and magnitude of the price increases (see the data in Table 1), without wage policy being able to react promptly. Therefore, the calculated development of real wages is more telling ex post with regard to the extent of the imported cost shock rather than a purposeful strategy of wage restraint by wage policy actors.

In the public debate, however, the comparison of nominal wage developments and inflation is often done differently: not ex post, but to classify current wage agreements in sectoral collective bargaining. Commentators determine the average increase in a collective agreement across all wage groups – which can require difficult calculations due to the various duration of agreements, the use of zero months clauses (i.e. the inclusion of “null months” before the first wage increase comes into effect after the signature), or the use of one-off payments and wage increases differentiated by wage groups. The result of such calculations can lead, for example, to a 5.0% wage increase. Now they compare this agreement with the currently observed inflation rate of, say, 8.0%. The result is in the negative, indicating wage restraint.

Table 1: Nominal wage increases and inflation in the Eurozone-16 (Q3 2021 – Q2 2023)

Note: The Eurozone-16 refers to all countries that were Eurozone members in 2021 with the exception of Cyprus, Luxembourg and Malta. Nominal wage increases refer to the percentage change in wages and salaries (total) in industry, construction and services when compared with the same quarter in the previous year. Inflation refers to the percentage change in the harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) compared with the same quarter in the previous year. Data from Eurostat.

We wish to warn against this approach since the change in real wages can only be determined ex post. The decisive factor here relates to the inflation developments during the term of a collective agreement, partly unknown to negotiators at the time of the contract’s signature. Worse still, price developments during the term of collective agreements are partly endogenous, that is, they are not completely independent of the very inflationary pressures (or the lack thereof) exerted by the nominal wage agreements. Consequently, real wage growth is also an endogenous entity.

The described approach is not desirable for it also suggests wrong conclusions. For example, the typical German wage settlement of 2022 or the first half of 2023 had a duration of at least 24 months. If we are correct in our assumption that inflation will continue to ease in the foreseeable future (as suggested by various institutions’ forecasts), then even the relatively low wage increases agreed in Germany (visible in table 1) could ultimately bring real wage improvements.

Wage restraint as deviation from the Golden Rule of wage-setting

The second concept of wage moderation is not based on the ex post observed real wage, but on the ex ante determinable cost pressures emanating from the supply side. These cost pressures can be compared against the inflation target of the European Central Bank, which is close to 2%.

The Golden Wage Rule, which the European trade unions have agreed on in the course of their rudimentary attempts to developed transnational wage coordination, is derived from the following simple consideration. In order to avoid a competitive race to the bottom in cross-national wage increases and to avoid some countries’ inflationary wage-setting to spill over into higher euro-wide inflation – which would prompt the ECB to react with restrictive monetary policy – euro area countries’ unit labour costs should rise by around 2% annually, the ECB’s inflation target. If unit labour costs (wage developments adjusted for productivity advances) rise by less than 2% annually, then there is wage restraint. On the contrary, unit labour costs’ growth outpacing this benchmark will tend to have inflationary effects.

The data in Table 1 indicates that wage developments in many countries have decoupled from the imperatives of the golden wage rule – medium-term productivity increases in the Eurozone are only about one percent, with only eastern European countries displaying some above-average increases. As a result of the deep inter-connection between wage and price inflation, the ECB is thus concerned about wage trends that are increasingly misaligned with (and above) its euro-wide inflation target.

The problem with the Golden Wage Rule is not its logic but – if it is really to serve as an imperative – its naivety. In the wage rounds from 2022 onwards, and ex post, the trade unions undoubtedly took into account the price surges and their members’ real wage losses during 2021. Nobody wants to pay membership fees to a trade union that ignores real wage losses. Thus, if these organisations want to survive, the greater the inflation rate is, the more their membership compels them to deviate from the imperatives of the wage rule.

This leads to a remarkable result: the Golden Rule works as a realistic imperative only when the central bank is succeeding in its mandate to keep price inflation anchored to its 2% target. A further implication is that, taking the trade unions’ perspective, the prolongation of inflation by means of price-wage spirals seems inevitable to some extent. The crucial question, in our view, is not whether such spirals occur. The question is rather how pronounced price-wage spirals are and, most importantly, how long they last.

In the past two years, wage negotiators all over Europe have found reasonable compromises, with results always located between the imperatives of the golden wage rule and the short-term inflation forecasts. Accordingly, wage developments contributed to the reduction of medium-term inflation. Moderate wage policy, though, could only be digested by trade unions because of generous fiscal spending by governments committed to compensating households through various forms of aid and social programs.

Wage restraint as a relational concept

The third concept of wage moderation brings together insights from the discussion of the first two. As we have seen, wage negotiators have had to mediate between two conflicting objectives over the past two years. They contributed to the medium-term disinflation with moderate settlements but, at the same time, they could not completely disregard their members’ concerns about current inflation dynamics and past real wage losses.

The latter implies that unions had to keep an eye on the specific inflation dynamics in their respective countries – rather than considering the euro area’s inflation target of 2%. In fact, as shown in Table 1, national wage developments were broadly anchored to national inflation developments: the higher the country’s inflation, the higher the national nominal wage increases – consider that, among the countries considered, wage indexation formally exists only in Belgium (and its effects can be seen in Table 1).

Is this close relationship between national wages and prices’ inflation good or bad? It is good when evaluated ex post from the perspective of real wage stabilisation (our first concept). The lagged linkage of wage growth to the previously observed inflation contributed to minimising the contraction of households’ consumption – albeit being unable to prevent it entirely. The situation is different when evaluated from the perspective of the cost pressures firms face in light of higher unit labour costs (the second concept). The high correlation between inflation and nominal wage developments means that additional cost pressures are exerted on firms precisely in the countries where price inflation is already high.

This is problematic in a monetary union. In the medium term, this mechanism risks reproducing different inflation levels in the Eurozone because the speed and the duration of the disinflation process varies across countries. As a result, real effective exchange rates diverge within the EMU. This is undesirable in a monetary union where competitiveness differentials can no longer be corrected by nominal exchange rate adjustments.

This is why, in the EMU, we would be better off thinking of wage restraint as a relational concept: the export competitiveness of those members of the euro able to defuse inflation pressures quicker improves to the disadvantage of other members unable to do so to the same extent and at the same speed. Over the years, the eastern European euro participants (but also, for example, Belgium) could run into a cost competitiveness problem. The southern countries, but also Germany, could find their way out of inflation comparatively early and as a result gain relative competitive strength.

A similar dynamic – i.e. divergence in countries’ real effective exchange rates-based competitiveness – occurred in the first decade of the common currency, contributing to the emergence of the euro crisis. Nothing guarantees that similar problems will not resurface. This time, however, in an inflationary environment and with monetary tightening already in place, the ECB’s willingness – or capacity – to help with mass bond purchases cannot be taken for granted. Even if no one is talking about it now, the inflation shock keeps confronting the Eurozone with a hard test. This means that the Eurozone is not out of the woods yet.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Marian Weyo/Shutterstock.com