Poorer European regions are often assumed to have less trust in the EU than richer ones. But is this always the case? Drawing on a new study, Sofia Vasilopoulou and Liisa Talving demonstrate that the relationship between regional inequality and trust in the EU is non-linear, with poorer and richer European regions tending to trust the EU more than middle-income regions.

Globalisation and the transformation of global capitalism from industrialisation to the knowledge and innovation economy have created winners and losers not only at the individual level but also at the subnational regional level. In Europe, some regions have experienced concentrated high-wage and high-skill employment, better quality of public services and overall better prospects for inter-generational mobility. These regions have been able to prosper and adjust in the knowledge economy.

Yet, other regions have felt the negative effects of globalisation, deindustrialisation and demographic shrinkage. They have faced long-term pressures resulting from the decline of manufacturing employment, are more exposed to the international economy and are more vulnerable to trade shocks. These regions have become disconnected from knowledge and innovation and tend to have lower levels of pay, skill and educational achievement.

How does this regional economic inequality influence trust in the EU? The literature thus far has viewed this relationship as the manifestation of the “revenge of the places that do not matter”. However, when examining support for European cooperation, this overlooks the fact that EU discontent has also been observed among rich regions as well as those middle-income regions that receive insufficient compensation from the EU.

To account for this paradox, in a recent study we argue that we need to pay more attention to a key type of region, namely the middle-income region. We posit that to fully understand the relationship between regional economic circumstances and EU trust, we should systematically investigate three dimensions of regional inequality: regional wealth status, regional wealth growth and regional wealth growth at different levels of wealth status. We show this empirically using individual-level survey data for EU27 countries and the UK from 11 Eurobarometer waves between 2015 and 2019.

Trust in the EU

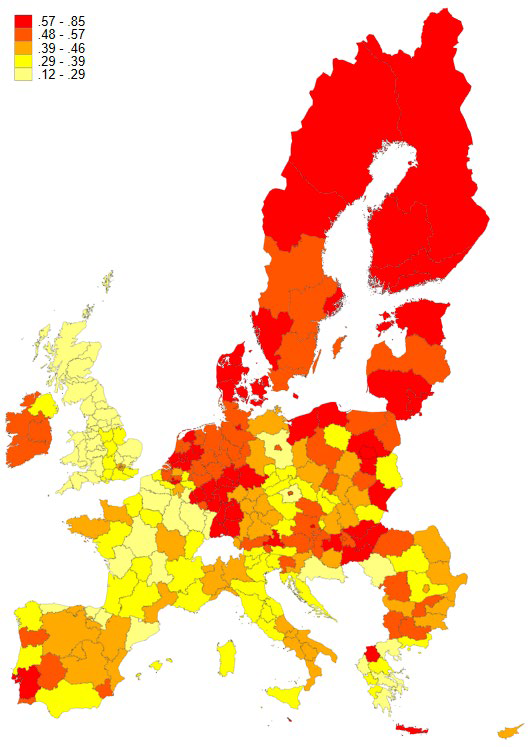

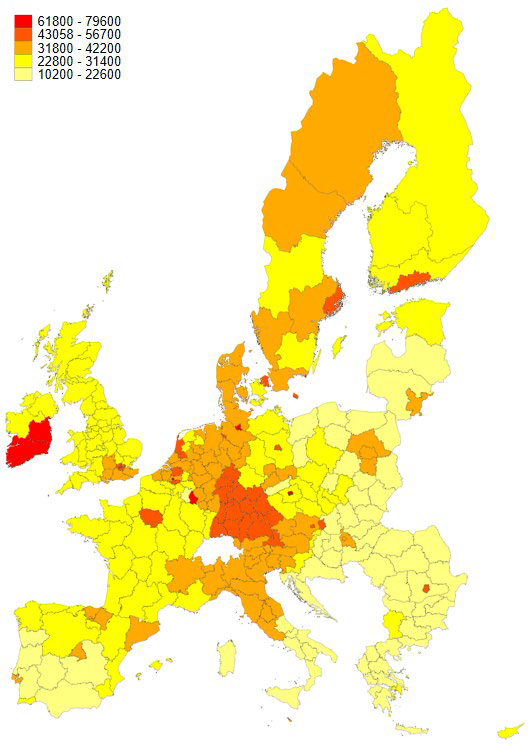

We commence by descriptively comparing levels of regional inequality and EU trust in 2019 (Figures 1 and 2). Trust in the EU varied in 2019 from 12 per cent in the Yorkshire and the Humber region in the UK to 85 per cent in Salzburg in Austria. The lowest average GDP in 2019 was recorded in the Northwestern region of Bulgaria (10,200 purchasing power standards – PPS – per inhabitant) and the highest in Luxembourg (79,600 PPS per inhabitant).

Figure 1: Regional distribution of trust in the EU

Note: Figure shows percentage trust in the EU. For countries where data on NUTS2 level were not accessible, NUTS1 was used instead. Trust data from Eurobarometer waves, 2019.

Figure 2: GDP per capita across Europe (PPS per inhabitant)

Note: For countries where data on NUTS2 level were not accessible, NUTS1 was used instead.

Regional economic status is not necessarily linearly linked to institutional EU trust. For example, trust levels during the observed time period are relatively low in some above average wealthy European regions, such as Carinthia in Austria (18 per cent on average) or Saxony in Germany (26 per cent), and high in some relatively poor regions like Southwestern Bulgaria (63 per cent) or South-West Oltenia in Romania (65 per cent).

Regional wealth status

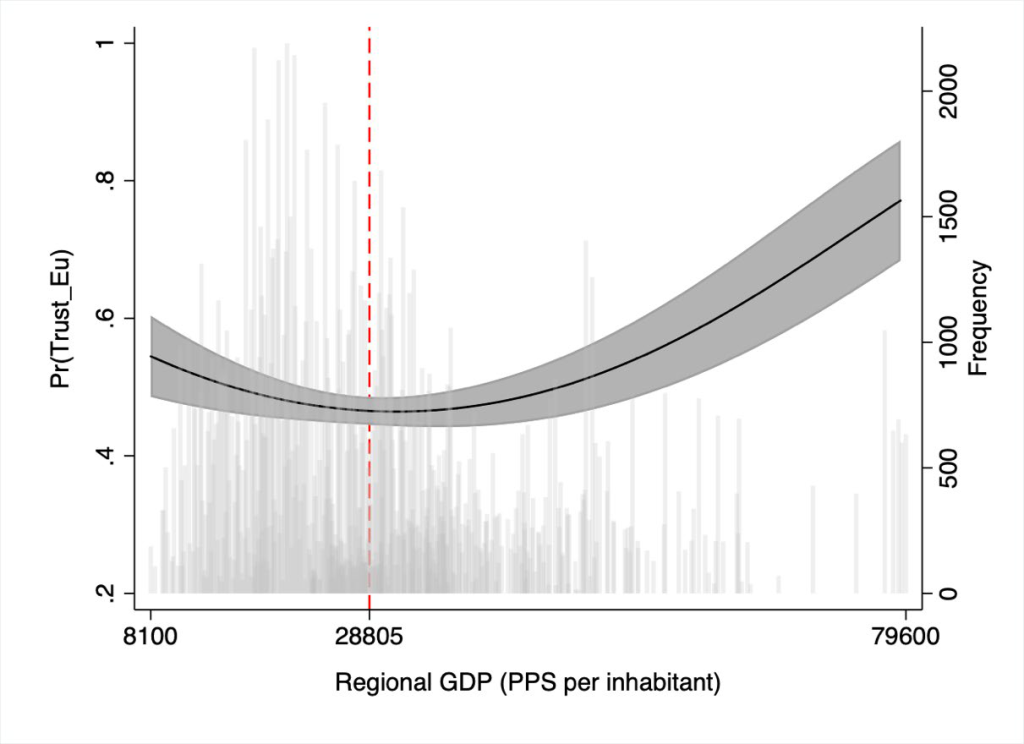

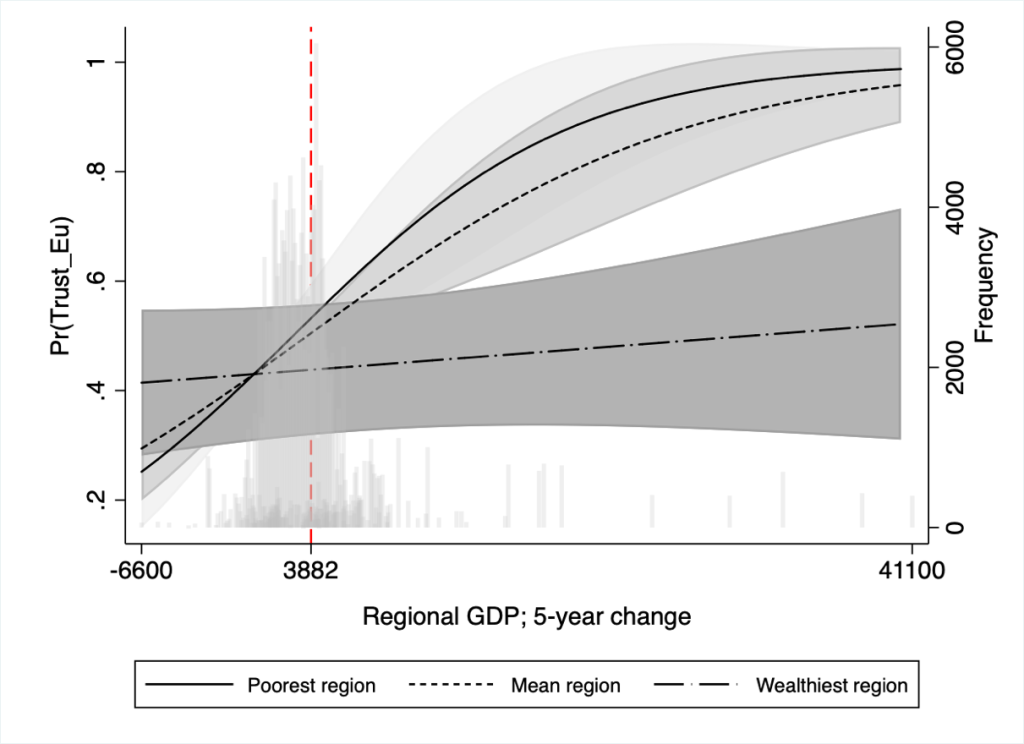

The relationship between trust in the EU and regional wealth status is non-linear (Figure 3). EU trust levels are highest among affluent regions of Europe, remain more modest in poor regions, but are lowest in middle-income regions.

Figure 3: Predicted probabilities of trust in the EU, at different levels of regional wealth status

Note: The histogram reflects the frequency distribution of regional wealth. Trust data from Eurobarometer waves, 2015-2019.

The predicted probability of trusting the EU is 78 per cent for individuals from the region with the highest income and 54 per cent for people from the region with the lowest income in the sample (Luxembourg in 2019 and Northwestern Bulgaria in 2015, respectively). However, middle-income regions lag behind, with only a 47 per cent likelihood of trusting the EU for mean regional wealth levels (red dashed line in Figure 3). Differences between all three regions are statistically significant.

Regional wealth growth

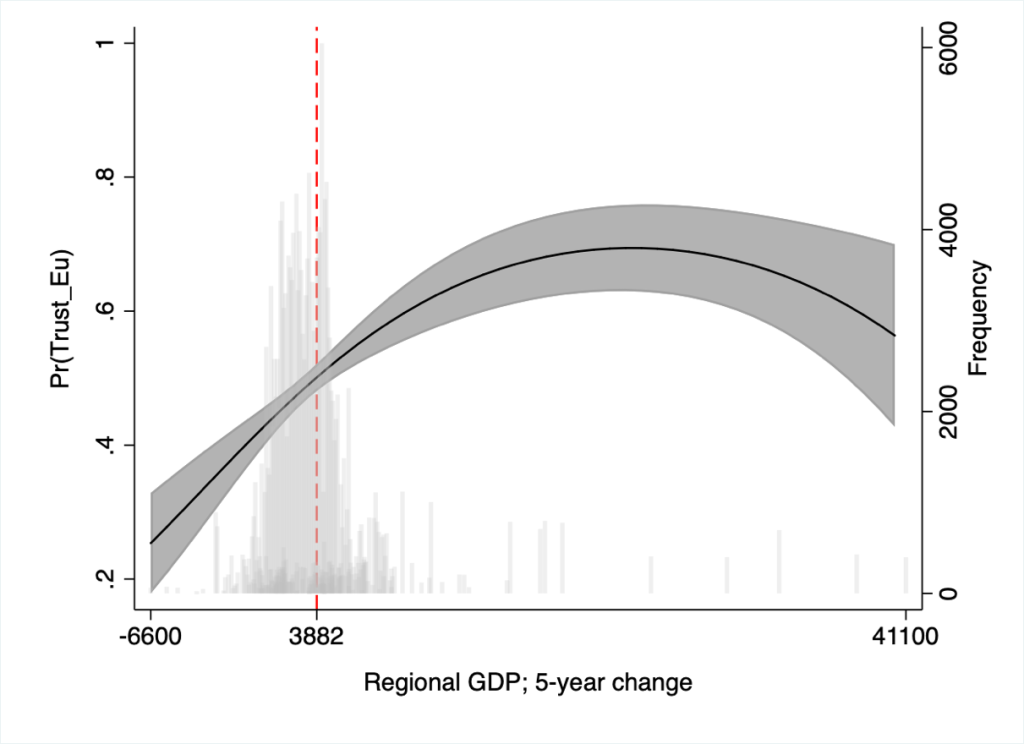

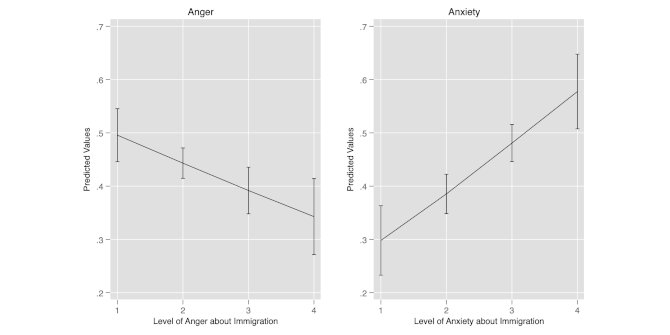

We propose that individuals compare their region to its own past and potential future trajectory. We demonstrate that within-region over-time growth is associated with higher levels of EU trust.

EU trust levels rise as regional wealth grows (Figure 4). The association is not linear, although the non-linearity seems to be driven by the low number of observations towards the upper end of the scale (see histogram). Highest trust probabilities are recorded in regions that have witnessed moderate or large wealth increases, although they start declining again in regions with very large wealth growth, potentially indicating a ceiling effect.

Figure 4: Predicted probabilities of trust in the EU, at different levels of regional wealth growth

Note: The histogram reflects the frequency distribution of regional wealth growth. Trust data from Eurobarometer waves, 2015-2019.

The probability of trusting the EU is 25 per cent for the region that went through the largest negative change in wealth during the observed period (Groningen in the Netherlands in 2018) and 55 per cent for the region that witnessed the largest positive change (the Southern Region of Ireland in 2019). For a region with mean growth (red dashed line in Figure 4), the likelihood of trusting the EU is 50 per cent. The latter region is not statistically different from regions with the largest growth.

Regional wealth growth at different levels of wealth status

The association between growth and trust in the EU is much more pronounced among poor and middle-income regions compared to rich regions. While poor and middle-income regions start out with a relatively low likelihood of trusting the EU, predicted probabilities rise as they experience more wealth growth (Figure 5). In rich regions, on the other hand, political trust remains stable, no matter how large the growth in income.

Figure 5: Predicted probabilities of trust in the EU, by regional wealth status and wealth growth

Note: The histogram reflects the frequency distribution of regional wealth growth. Trust data from Eurobarometer waves, 2015-2019.

Our analysis shows that the relationship between regional wealth status and trust in the EU is non-linear: Europeans living in middle-income regions are least likely to trust the EU. However, trust is not only a function of wealth status but also wealth growth.

Larger income growth generally yields higher probabilities of trusting the EU, although there seems to be a ceiling effect in regions that have experienced very large growth. We also find that institutional trust is dependent on the combination of wealth status and wealth increase. The likelihood of trusting the EU is highest in low or middle-income regions that experience larger growth. In rich regions, EU trust is not dependent on wealth growth.

Taken together, our findings show that Euroscepticism is not a poor region phenomenon, rather it is primarily found in the regions that are stuck in the middle in a development trap. Our findings speak to the need to recognise diversity in the “places that do not matter” and that scholarship should reconsider the perhaps oversimplified distinction between the “losers” (poor) and “winners” (rich) of globalisation.

By focusing on growth and prospects for growth, our findings shed light on the counter-intuitive finding that Euroscepticism can be simultaneously found in relatively wealthy and much less prosperous areas. It is, we argue, the problem of stagnation and lack of growth that accounts for this puzzle. More broadly, we point to the fact that citizens make sense of politics through their lived experiences and take cues from their community. Localised economic experiences give rise to different narratives through the prism of which individuals make sense of the political world.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper at the Journal of European Public Policy

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: symbiot/Shutterstock.com

Presumably some in the very poor regions instead feel more let down by their national governments, and have nothing to lose by still trusting the

(usually) recent EU involvement.